Renowned professor emeritus and musicologist H. Colin Slim met Igor Stravinsky in 1952 and again in 1966, events that inspired a lifelong interest in the composer’s personal and professional life. His collection of Stravinsky ephemera, manuscripts, and documents was donated to the University of British Columbia, which published an annotated catalog of the collection in 2002.

Stravinsky was born today in 1882, the perfect occasion to share an excerpt from Slim’s recent book, Stravinsky in the Americas: Transatlantic Tours and Domestic Excursions from Wartime Los Angeles (1925–1945).

Excerpt from Part 1, Chapter 2

New York

Stravinsky and Dushkin arrived in New York on the SS Rex on 3 January 1935, together with many other musicians: pianists Joseph Hofmann and Ignaz Friedman, and cellist Gregor Piatigorsky. Also disembarking was violinist Nathan Milstein, who later came to dislike Dushkin’s transcriptions of Stravinsky works. Milstein amusingly described the composer’s terror during the stormy voyage and Stravinsky’s on-board reediting for cello with Piatigorsky of the final movement in Dushkin’s 1932 arrangement of Suite italienne. Stravinsky and Dushkin stayed in New York until 11 January before setting off for the Midwest. They gave at least sixteen duo-recitals across the country.

Just four days after arriving in New York, Stravinsky was honored by a concert of his music given by the League of Composers at the Town Hall Club. Nicholas Slonimsky was president of the League, and Claire R. Reis its executive chair. A previous concert led by Slonimsky at the Hollywood Bowl on 16 July 1933, including what was mysteriously entitled Stravinsky’s Fanfare for a Liturgy, probably helped Slonimsky and Reis two years later in convincing the League to put on an all-Stravinsky concert. The Town Hall Club was “packed.” Perhaps owing to the lukewarm reception in 1925 of then-recent works such as the Octet and the Piano Concerto, every work heard that evening in 1935 was decidedly retrospective in nature: Three Pieces for String Quartet (1914), a group of songs (composed 1908–18), an aria from Mavra (1922), the Serenade (1925), and the Concertino for String Quartet (1920).

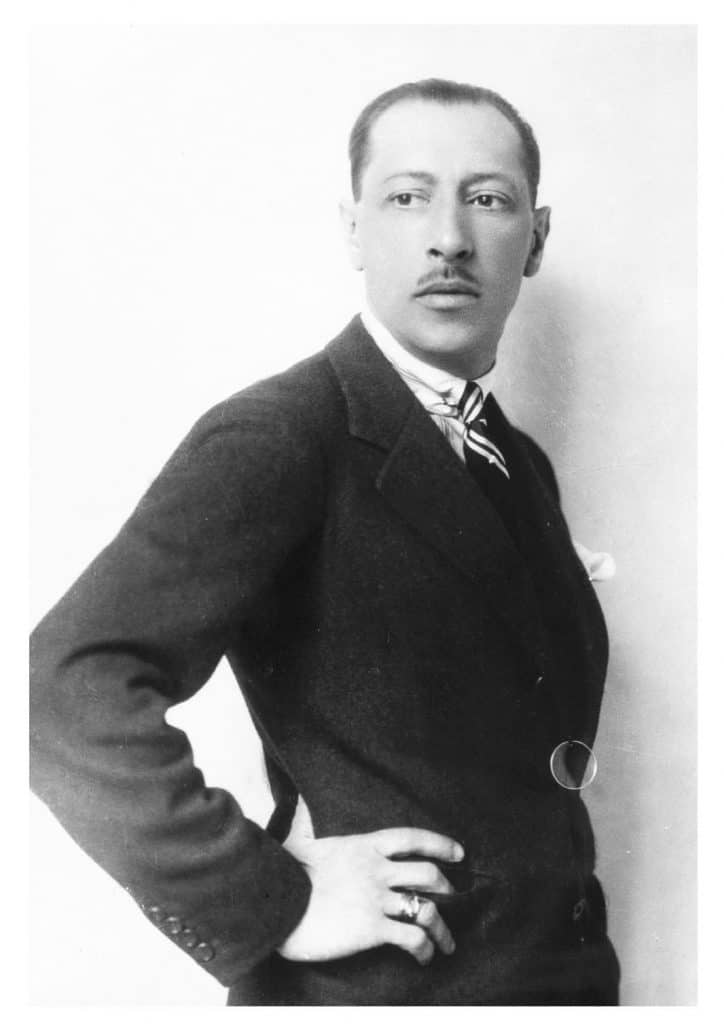

Appropriately enough, given the compositional divide suggested by the dates of these works, an announcement for this concert featured a photograph taken by the Studio Lipnitzki and already run in 1925 by Musical America. The image effectively sliced Stravinsky in two. Using only the upper half of the photograph, it omits the portion of the portrait that shows an elegant dangling monocle, a trademark during that decade (fig. 2.1). Just six weeks later in California, he was to inscribe a copy of the same but full Lipnitzki portrait to Herbert Stothart, the general music director of MGM Studios.

Portrait by Lipnitzki. Igor Strawinsky Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation, Basel.

Apropos of this concert, the young Alexander Steinert, then conductor of the Russian Opera Company of New York, related three years later:

[It was] merely by chance that I happened to be at a reception in honor of Stravinsky, given by the League of Composers at the Town Hall in New York during the winter of 1935. A slight tap of the shoulder caused me to turn around. It was George Gershwin.

Steinert landed the job of coaching singers for the forthcoming production in October of Porgy and Bess. Because Gershwin attended this Town Hall concert, Stravinsky probably encountered him there; if so, it was their third meeting: the first had been in 1925 in New York, and the second in 1928 when Gershwin visited Paris.

One recent biographer implies that both Stravinsky and Dushkin performed at the League of Composers concert. Neither did, although Dushkin probably also attended it. The concert received a devastating review, signed with the initials of a prolific but minor composer and longtime editor-in-chief for Musical America: A. Walter Kramer. Kramer complained of the utter sterility of [Stravinsky’s] lesser music in the light of today. . . .

Something of a tragedy it is to observe the impotence, the dryness, and the willful, wayward, cerebral direction of a musician of cultivation and considerable technical skill. There was not a single phrase of thematic material in all the works performed worthy of a post-graduate student. As for the terror which this music once aroused, it was no longer in evidence. Nothing but its arrant ugliness has remained. Mr. Stravinsky was present, bowed, and at the close of the evening was introduced to many who told him how much they enjoyed his music. There were also many who did not.

Neither critic nor composer then knew how much influence Kramer would have on Stravinsky’s finances only five years hence.

Three days later, on a program shared with several others for a “Morning Musical,” held on 10 January in the ballroom of the Plaza Hotel, Stravinsky and Dushkin first performed together in New York. Despite the completion in 1932 of the great Duo concertant, their share in this program consisted exclusively of transcriptions and arrangements. Among such works was a genuine novelty, the Divertimento, comprising excerpts arranged from Le Baiser de la fée, an arrangement that they had just premiered the previous month in Strasbourg. A reviewer of this “3rd Artistic Morning in the Hotel Plaza” who praised “Stravinsky’s pianism . . . exact and fluent” also observed that “Mary Garden was in the audience.” In its orchestral garb, his Divertimento was to figure in this tour, in the 1936 one to South America, and in both trips to Mexico in 1940 and 1941.

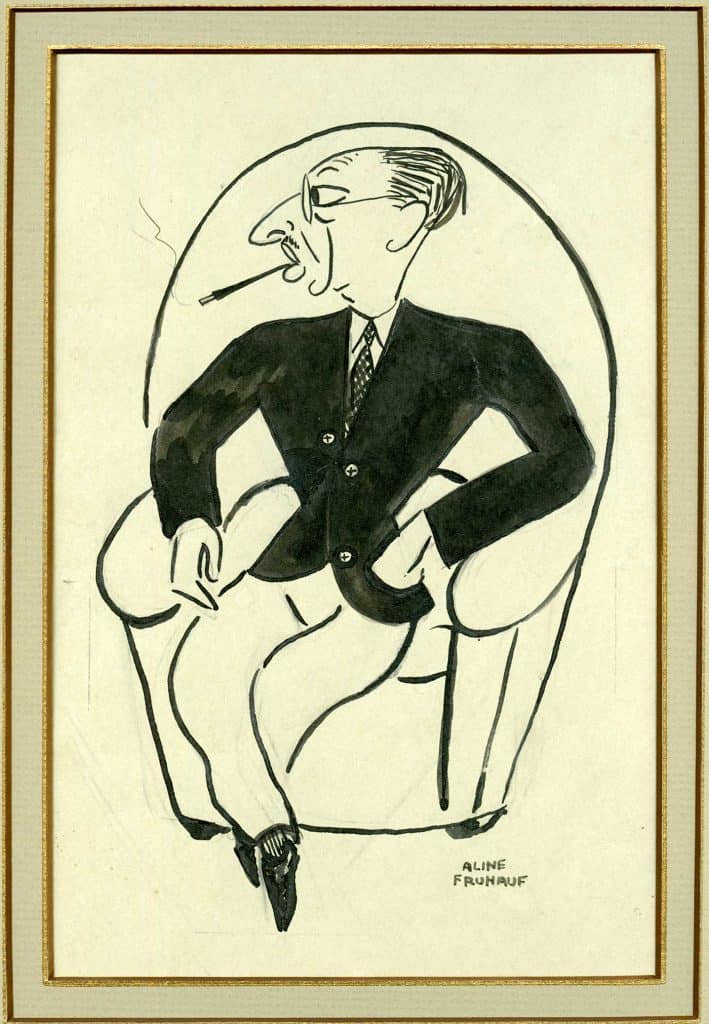

At some point after he and Dushkin arrived in New York, although perhaps not during their first busy week there, the dapper Stravinsky sat—apparently more than once—for a drawing by Aline Fruhauf (fig. 2.2). Commissioned by Musical America, it appeared in the April issue. Not only her drawing but also her perceptive recollection of their meeting deserve reproduction here:

He was a small man with broad shoulders, a slim waist and a propulsive profile. At first his long, ovoid head suggested an Aztec carving; then it became a blanched almond. . . . At the first meeting, Stravinsky’s hair was brownish and beautifully groomed, I was sure, with a pair of military brushes. He was well turned out in gray flannels, a chocolate-brown cardigan, a gray striped shirt with a white collar, and a brown foulard tie with copper dots. And his image was punctuated by a large onyx ring on his right hand, pointed black shoes, and a cigarette in a long black holder.

As Fruhauf related, when she “went to the office to pick up [the original] after it had been published, I found that one of my anonymous collectors had gotten there first.” Who stole the drawing is not known, but one owner’s initials, “D B W,” were stamped on her drawing before it was acquired sixty years later by the New York dealer from whom I purchased it.

Cartoon by Aline Fruhauf, 1935. UBC Stravinsky Collection, no. 39.