William Gow was awarded the Western History Association’s 2019 Vicki L. Ruiz Award, which recognizes the best article on race in the North American West for his article, “A Night in Old Chinatown: American Orientalism, China Relief Fundraising, and the 1938 Moon Festival in Los Angeles,” published in the Pacific Historical Review. We are pleased to make this article free to read online for a limited time. William Gow sits down with Evyn Lê Espiritu Gandhi to discuss his work. #WHA2019

EG: Tell me the origin story of this article. When did you first begin working on it?

WG: I feel in Ethnic Studies origin questions are always somewhat difficult to answer. Like many researchers in Asian American Studies, I have personal connections to this topic. My paternal grandfather and his brothers and sisters were all US-born Chinese Americans who lived in Southern California in the late 1930s and 1940s. After I received my MA in Asian American Studies from UCLA, I wanted to examine this aspect of my own history more closely. While working as a public school teacher in the LA area, I spent nearly eight years as a volunteer historian and documentarian with the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California (CHSSC). Despite being named a “Chinese Historical Society” the organization is actually one of the nation’s oldest historical societies devoted to the history of Asian Americans, with a specific focus on Chinese Americans in Southern California.

During my eight years with the CHSSC, I conducted oral histories with dozens of Chinese Americans who lived, worked, or played in Chinatown during the World War II era. This work inspired the proposal for my doctoral dissertation—now book project—on Los Angeles Chinatown and its relationship to Hollywood and performance in the 1930s and 1940s. My essay for Pacific Historical Review was adapted from my work on that larger project.

EG: Given your research with the CHSSC, what motivated you to tell this story about how the 1938 Moon Festival presented Chinese Americans in Los Angeles a unique opportunity to rework American Orientalist iconography and perform, in your words, “on a stage of their own creation”?

WG: As a scholar I am interested in the ways in which seemingly everyday people utilize popular culture to negotiate the dominant conceptions of race and gender that have long shaped so much of their lives in the United States. Historically, dominant conceptions of race and gender do not shift on their own. Rather, they do so as a result of the actions, choices, and decisions of actual human beings working within larger social structures. Too many scholars either forget this or get caught in theoretical models that don’t allow them to acknowledge this.

Historians have long identified the World War II era as a turning point in the racial formation of Asian Americans, yet too often this shift is ascribed to the shifting geopolitical alliances of the Pacific War, with the agency of everyday Asian Americans left ignored or under-examined. So-called Bowl of Rice Festivals as well as related China Relief fundraisers during the late 1930s and early 1940s are a case in point. These celebrations were hypervisible. They were covered by the largest media outlets of the day. Yet at the same time, we know relatively little about the Chinese American women and men who participated in these festivals. Who were they? What motivated them? How did they conceive of their performances and other forms of participation?

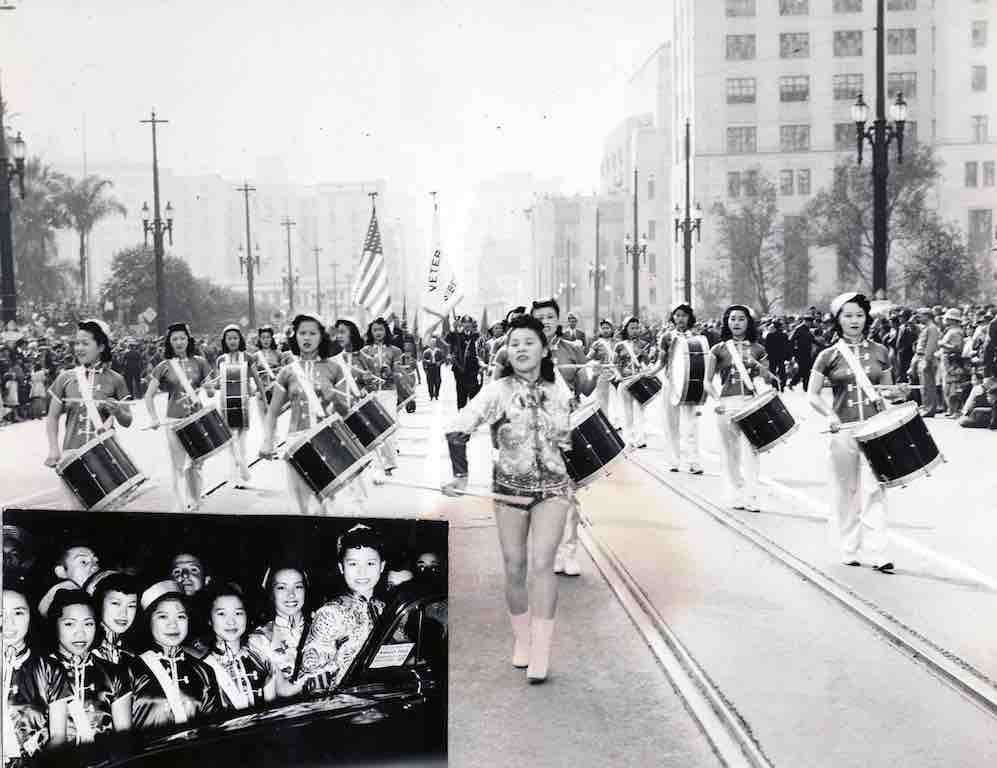

There is perhaps no clearer example of this than the Los Angeles Mei Wah Girls’ Drum Corps, which had its birth at one of these festivals and whose genesis I document in my article. The group’s majorette Barbara Jean Wong was a local Chinese American celebrity. She was an actress and a radio star. As for the drum corps itself, the local and national press covered the group’s public performances. A few scholars such as Valerie Mastumoto and Shirley Jennifer Lim have discussed them, but this group certainly warrants much more scholarly attention than they have garnered to date. Barbara Jean Wong alone warrants her own book.

EG: Speaking of books, above you mentioned your book project on Los Angeles Chinatown and its relationship to Hollywood and performance in the 1930s and 1940s. Tell me more about your larger book project and how this article fits into it.

WG: Yes, the larger book project focuses on Chinese American performances for white audiences both in Chinatown and in Hollywood film as background extras and bit players in the 1930s and 1940s. My project examines both the ways in which these Chinese American performances shaped the performers’ own conceptions of their identity as ethnic Chinese people living in the United States, as well as the ways in which Chinese Americans were able to utilize these performances to contest, and at times reinforce, dominant ideas of China and Chinese people in the United States. For example, one of my chapters looks at MGM’s film The Good Earth released in 1937. In scholarly circles, so much attention has been paid to the role that Pearl Buck’s book played in shaping American conceptions of Asia, but relatively little attention has been given to the film. This is surprising because as a cultural work far more people globally watched the film than read the book. In the Depression, film along with radio were the most popular forms of mass-entertainment in the US. Yet critics often dismiss the movie because it features two white film stars—Luise Rainer and Paul Muni—in yellowface make-up while passing over Anna May Wong for a lead role.

While this history is of course important, the film reportedly featured over 1,000 extras in the background. Most of these background performers were Chinese Americans recruited from Los Angeles. According to the US census, there were only around 4,000 Chinese Americans living in Los Angeles during this period. Given this, literally everyone in Chinatown was either in the film, had a relative in the film, or knew a friend in the film. And this movie is only one of a whole cycle of China films produced in Hollywood in the 1930s. Others include Shanghai Express (1932), The Bitter Tea of General Yen (1932), The General Died at Dawn (1936), and Lost Horizon (1937), just to name a few. Any Chinese American in Los Angeles who wanted to appear in the movies in the 1930s could have done so.

Since the release of Crazy Rich Asians, there has been a lot of focus on issues of Asian American representation and what it means for young Asian Americans to see themselves on screen. But when journalists and scholars say this they mean it figuratively—that is, what does it mean to see a person who looks like you on screen? If you were a Chinese American living in Los Angeles in the 1930s, you could literally see yourself—or your sister, your cousin, or your mother—on screen. I’ve interviewed a number of Chinese Americans from the period who lived in Los Angeles and who recall watching these films when they were released. When these Chinese Americans watched movies like The Good Earth, they weren’t focusing on the white movie stars in the foreground or even on the racist plotlines of many of these films. They were focusing on themselves in the background! This is the importance of performance to this generation of Chinese Americans.

EG: As you mention in your article, the 1938 Moon Festival was organized in part in response to the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War of 1937. You write that this Moon Festival marked a point of transition in shifting Yellow Peril stereotypes away from China and the Chinese American community, and towards Japan and the Japanese American community in the American popular imaginary. This is a very interesting history of inter-ethnic tensions that sometimes gets overshadowed by the more dominant historical narrative of the pan-ethnic Asian American Movement of the Long Sixties, which wouldn’t occur until several decades later. I’m wondering if you could say more about the challenges of conducting research on early Asian American history; your work is definitely informed by the institutionalization of Ethnic Studies in the late 1960s and the field’s political motivations, and yet the historical period of your research focus precedes that moment of political articulation. Can you say more about how you navigate this dynamic as a scholar?

WG: My project is deeply indebted to the work of Asian American community historians who came before me. This article and my larger book manuscript makes ample use of the Southern California Chinese American Oral History Project, which was a joint project in the 1970s between members of the CHSSC and the Asian American Studies Center at UCLA. The project includes more than 400 hours of interviews with more than 160 people, nearly all of whom were Chinese Americans in Los Angeles. The project is now housed at UCLA Special Collections. The project also produced one of the first books of Asian American women’s history in 1984, Linking Our Lives: Chinese American Women in Los Angeles.

This oral history project really epitomized the ethos of Ethnic Studies during this period. Its because of the work of community scholars like Suellen Cheng, Beverly Chan, Bernice Sam, Emma Louie, John Yee, Munson Kwok, and others who conducted these oral histories that I am able to produce the work I do today.

I am also at work on a second book project that traces the rise and decline of community history in Asian American Studies between 1969 and 1989 and what the general collapse of this approach means for the state of our field. In the ensuing decades, as the primary site for the production of Asian American history has moved from the interdisciplinary field of Ethnic Studies to the more established discipline of History, this particular methodology of community history has been marginalized. What’s more, the work of this generation of community members, whose scholarship is really the foundation of Asian American historiography, is often dismissed by professional historians as irrelevant or as too amateurish to cite. Furthermore, these works and their methods are rarely taught in graduate programs. Books like Linking Our Lives are an example of this era of scholarship.

Of course there are still a few folks who do this type of community history work. I think of the Viet Stories: Vietnamese American Oral History Project at UC Irvine or the scholarship of the late Dawn Mabalon. But really, Asian American Studies scholars need to realize that the foundation of Asian American history cannot be written from the traditional archive alone. Those archives are too rife with silences to completely tell our communities’ histories. Instead, we need to reconceive of our communities—with their photo albums, basement collections, and personal memories—as our primary “archive” and work to build the type of connections in the community that allow us to access this archive. Finally, we have to tell these stories to the community in ways that are accessible to them. For me, this has often taken the form of my digital documentary work. We in Asian American Studies ignore this methodology at our own peril.

EG: I’m excited to check out your digital documentary work, and I look forward to reading your book when it comes out! Thanks for inviting me to be a part of this conversation.

WG: Thanks for all your wonderful questions! It’s been a pleasure discussing my work with you.