With communities, states, and nations taking action to defend themselves from the most dangerous fast-moving pandemic in a century, we are reminded of the government’s role in public health emergency preparedness and response. In this excerpt from Lawrence O. Gostin and Lindsay F. Wiley’s Public Health Law: Power, Duty, Restraint, the authors explain the roles of U.S. federal, state, and local governments, emergency declarations and the authorities and resources they invoke, the use of quarantines, physical distancing, and community containment strategies, the allocation of scarce health-care resources and personal protective equipment, and the development and distribution of effective medical countermeasures such as vaccines and antivirals.

Chapter 11 of Public Health Law is available in full by visiting this link.

Everybody knows that pestilences have a way of recurring in the world, yet somehow we find it hard to believe in ones that crash down on our heads from a blue sky. There have been as many plagues as wars in history; yet always plagues and wars take people equally by surprise.

—Albert Camus, The Plague, 1948

Terrorist attacks, novel influenzas, emerging infectious diseases, and natural disasters have prompted a reexamination of the nation’s public health system. The jetliner and anthrax attacks of 2001, the SARS outbreak of 2003, hurricanes Rita and Katrina in 2005, the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, Hurricane Irene in 2011, Hurricane Sandy in 2012, the Texas fertilizer plant explosion in 2013, and the West African Ebola epidemic in 2014–15 have focused attention on public health preparedness. In the years following the 2001 attacks, “the conceptual framework of emergency preparedness and response subsume[d] ever larger segments of the fi eld of public health.”1 The outpouring of resources and attention to biosecurity has supported a public health law renaissance. Perceived government failures in response to public health emergencies continue to stoke public anxiety, adding political pressure for more effective preparedness planning.

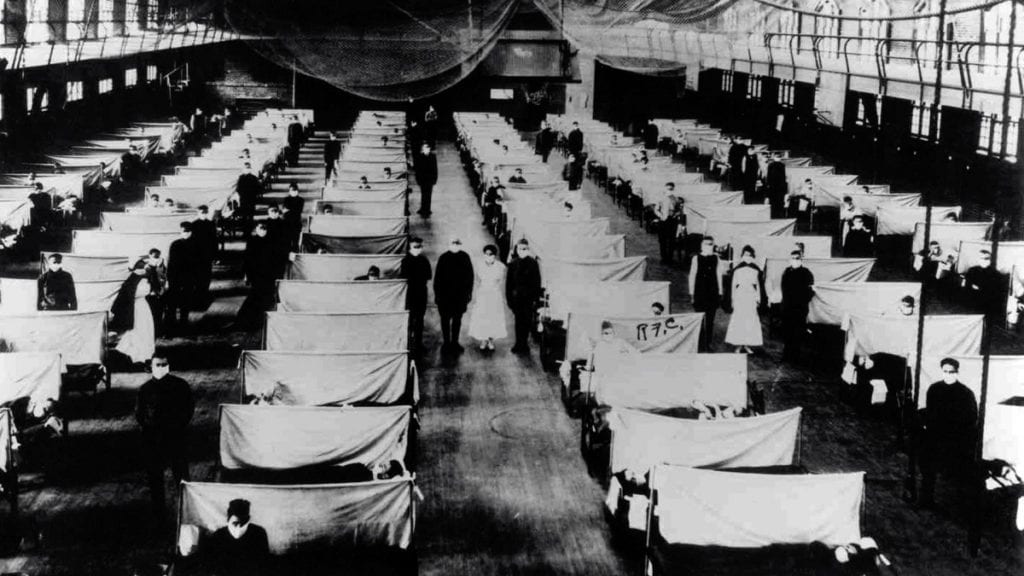

buildings, such as community centers and schools, were transformed into temporary hospitals to care for the staggering number of patients. Courtesy of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Public Health Historian.

All-hazards and resilience have become watchwords in preparedness. Vertical strategies targeting specific threats (e.g., development of pathogen-or toxin-specific vaccines and treatments) remain a priority. But horizontal strategies (e.g., investment in public health infrastructure) are needed to ensure preparedness for a broad range of emergencies while also enhancing capabilities to meet routine needs. At the federal level, the National Response Framework (NRF) integrates existing preparedness, response, and recovery programs to “align key roles and responsibilities, . . . guide how the Nation responds to all types of disasters and emergencies,” and ensure “security and resilience.” At a time when governments are investing significant resources in preparedness for rare events that may never occur, it is politically useful to frame these expenditures and legal reforms as supporting preparedness for more likely events such as natural disasters. And in practice, obvious benefits derive from expanding public health infrastructure’s capacity to handle routine needs.

Modern public health emergency preparedness strategies continue to draw on ancient public health law interventions such as isolation and quarantine while also adopting updated approaches to social distancing, development and rapid deployment of medical countermeasures, and allocation of scarce resources under exigent circumstances. Policies must delicately balance protecting individual rights with meeting collective needs, promoting cooperation and coordination across jurisdictions, and ensuring fairness in meeting the needs of particularly vulnerable populations. We begin by examining the federal-state balance in public health emergency preparedness. We then follow the emergency planning cycle, discussing disaster and emergency declarations; evacuation and sheltering; development and rapid deployment of medical countermeasures; and isolation, quarantine, and social distancing.

The Federal-State Balance in Public Health Preparedness

Public health emergency preparedness addresses hazards and vulnerabilities whose scale, rapid onset, or unpredictability threatens to overwhelm routine capabilities. It encompasses chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear exposures (CBRN) as well as natural, industrial, and technological disasters (e.g., hurricanes, floods, earthquakes, dam failures, and radiation leaks), all of which require advance planning, rapid detection, and effective response. Threats may be naturally occurring (e.g., emerging disease outbreaks), or they may originate from intentional acts (e.g., terrorism) or unintentional releases (e.g., chemical spills). Biosecurity refers to precautions against the spread of harmful microorganisms, but it is sometimes used more broadly to refer to all public health emergencies. Biosafety (a related concept) refers to the maintenance of safe conditions in biological research to prevent inadvertent escape of hazardous materials. Biological samples can create major hazards when researchers do not use rigorous containment procedures.

Public health emergencies unite one of the most fundamental functions of the federal government—national security—with one of the most fundamental functions of the state governments—public health. Public health emergencies pose enormous challenges to American federalism, with myriad laws at the local, state, tribal, and federal level—many of which were developed “to address more mundane public health matters, or designed to respond to more traditional emergency situations.” This federalist structure has resulted in conflicting jurisdictional claims as well as confusion about, or even denials of, ultimate responsibility in times of disaster management.

The jetliner and anthrax attacks of 2001 launched more than a decade of capacity building, including reforms of long-standing federal disaster and emergency response laws and state public health laws. Many reforms were dramatic, including the largest restructuring of the federal administrative state since the New Deal with the newly created Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the establishment of federal direct-response systems for medical resources and personnel. At the state level, the Model State Emergency Health Powers Act was adopted to some extent in thirty-nine states and the District of Columbia. The vast expansion of emergency preparedness laws has raised concerns about coordination among different levels of government, interagency coordination within each level of government, and protections for individual rights.

Since the mid-twentieth century, the federal government has assumed responsibility for financing disaster recovery efforts that overwhelm local resources, thus spreading the economic burden of disasters. Through health, safety, and environmental regulation and the administration’s national security and international development agendas, the federal government also plays a leadership role in prevention and mitigation. This is particularly true with regard to terror attacks and global pandemics, though climate-change mitigation efforts have been stymied by political gridlock. The federal government regulates biologic agents of public health concern, conducts surveillance for emerging infectious diseases (see chapter 9), and provides financial support and guidance for state and local government preparedness efforts. In recent years, the federal government’s increasing role as a direct provider of services—not merely a financier and adviser to state and local governments—represents a major expansion of its preparedness and response efforts.