It has been well understood for some time now that COVID-19 and its ensuing global pandemic are unprecedented events in our contemporary world. Not since the Influenza Pandemic of 1918 has global life been so drastically altered so quickly due to a viral outbreak.

In the century since 1918, countless individuals, organizations, and nations have striven to eradicate the unnumbered diseases, parasites, and structural barriers that cause unnecessary death, needless suffering, and the squandering of human potential.

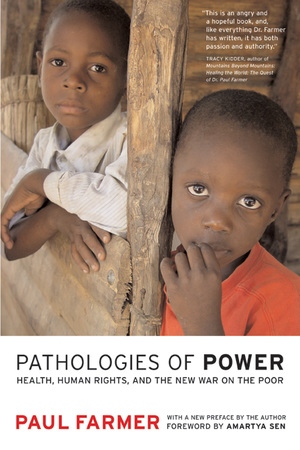

Paul Farmer is one of those individuals. Chair of the Department of Global Health and Social Medicine at Harvard Medical School, Farmer is co-founder of Partners in Health, serves as a Special Advisor to the United Nations, and has authored several books on the topics of global health, human rights, and international cooperation.

Given our aforementioned collective moment in history, UC Press would like to bring renewed attention to these topics and Farmer’s role as a leading public figure.

The following is an excerpt from Pathologies of Power: Health Human Rights, and the New War on the Poor (2004), chapter 6, “Listening for Prophetic Voices.”

But tell me, this physician of whom you were just speaking, is he a moneymaker, an earner of fees or a healer of the sick?

Plato, The Republic

The Old Testament prophets cannot have had a very easy time of it, and not because their primary work was as clairvoyants or seers. Prophetic voices were more often raised in protest against the social conditions endured by widows, orphans, and the poor majority. These voices were raised in opposition to structural violence—the poverty and inequality that meant opulent excess for a few and misery for most. Many prophets were regarded by their literate contemporaries as certifiably mad; few were heeded.

In some ways, the prophets failed, for the inequities they deplored still endure. A growing and globalizing market economy has not, as promised, lifted all boats. Instead, increasing wealth has meant entrenched excess and squalor. We read in the newspapers of famine and strife, but also of the stunning sales of luxury items. The Roaring Nineties were notable for waiting lists for $4,000 handbags and $44,500 watches; $75,000 cars sold like hotcakes. The new millennium dawned not with Armageddon but rather with the spectacular success of free-market capitalism, so long as “success” is measured in terms of gross national product, the number of billionaires, or the volume of the stock exchange. Although recent events—including the attacks of September 11, 2001, and the very public unraveling of a giant “energy” company that in fact did little in the way of generating energy—have dampened the fervor of the preceding decade, it is clear that rich countries remain rich, and most rich people remain very, very rich. The much-discussed collapse of the stock market has not come to pass; it is not even clear that markets have contracted in any significant, enduring way. As both wealth and poverty continue to rise, many of the most affluent have managed to escape with their capital gains intact. “America,” observes Christopher Jencks in a recent review, “does less than almost any other rich democracy to limit economic inequality.”

Indeed, a less heartening picture emerges when economic and other forms of social inequality are scrutinized, for they are growing at an even more rapid pace. Inequality is very much the sign of our times. By almost every measure, social inequalities—both within affluent societies and across borders—have risen sharply over the past two or three decades. The social pathologies associated with rising inequality give pause to even the cheerleaders of neoliberal economics. More thoughtful students of inequality are persuaded that there are many reasons to limit it. “My bottom line,” concludes Jencks after decades of studying the topic, “is that the social consequences of economic inequality are sometimes negative, sometimes neutral, but seldom—as far as I can discover—positive.”

It’s clear that modern biomedicine, like the global economy, is booming. Never before have the fruits of basic science been so readily translated into life-promoting technologies. Headlines abound with news of sequencing the entire human genome, of effective organ transplants, of new drug development. Every affliction, even many of the indignities of normal aging, must have its response, as the therapeutic armamentarium grows and the desire for health makes the pharmaceutical industry the most profitable of all major industries. But inequalities of access and outcome increasingly dominate the health care arena, too. Every victory is marred by a troubling counter-story: protests of indigenous people against the Human Genome Project; grisly stories of organs stolen or coerced

from the poor for transplant to the bodies of those who can pay; great enthusiasm, on the part of drug companies, for the development of new drugs to treat baldness or impotence while antituberculous medicines are termed “orphan drugs” and thus deemed not worthy (based on profitability) of much attention from the drug companies.

Medicine-as-commerce is at the heart of each of these stories, just as it is at the heart of some of the good trends and most of the bad ones. It is clear enough that biotech and pharmaceutical firms can work miracles. But it is also true that they lean heavily on public funding and end up making a great deal of private profit. Even more troublesome are the rapidly growing investor-owned health plans. They go under many names, including health-maintenance organizations. Although some of these are not-for-profit, many have in common a basic strategy: selling “product” to “consumers” rather than providing care to patients.

In an essay critiquing the shift toward the commodification of health care, Edmund Pellegrino argues that health care cannot be considered a commodity, one like food or clothes, that fits into its appointed place in the American free-market system. The highly championed view of market forces as the ideal mechanism driving the distribution of goods and services in a democratic society cannot be extended to the medical profession. The ends and purposes of medicine are unique, since they are linked to issues of individual trust and common good: “healing [is] a special kind of human activity governed by an ethic that serves those ends and not the self-interests of physicians, insurance plans, or investors.”

What happens when health becomes a commodity and doctors conduct “commercial transactions” with patients, in a climate where managed-care corporations are the “providers”? Pellegrino cautions that business ethics do not translate well to medicine:

Inequalities in distribution of services and treatments are not the concerns of free markets. Denial[s] of care for patients who could not pay were not unknown in the past. But they were not legitimated as they are in a free market system where patients are expected to suffer the consequences of a poor choice in health care plans. . . . In this view, inequities are unfortunate but not unjust. Some simply are losers in the natural and social lottery. The market ethos does not per se foreclose altruism, but neither does it impose a moral duty to help.

Theoretically, if the market ethos rules health care, “physicians would be justified in refusing care” on the grounds that “patients are responsible for their own health.”

In the United States, investor-owned health plans have rapidly transformed the way we confront illness. Despite much talk of “cost-effectiveness” or “reform,” the primary feature of this transformation has been the consolidation of a major industry with the same goal as other industries: to turn a profit. Emboldened by obscenely large salaries and stock options, the captains of this emerging industry are unselfconscious, almost shameless, about their plans for American medicine. One commentary, in advancing a “code of ethics for the medical-industrial complex,” puts it boldly enough: “Make a profit: economies involving scarcity are bad for everyone . . . . Therefore, be good to people and make money.” Furthermore, the health care system should “help people buy what they want.. . .Therefore, people should be allowed to purchase health care packages that provide limited or less than optimal care. As a matter of justice, they should also be allowed to receive only the health care services that their coverage allows.” Writing in the New England Journal of Medicine, one of the cheerleaders for this new, soulless trend stated flatly: “there is no longer a role for non-profit health plans in the new health care environment.”

Neither is there a role for the “fungible” patients, as one acidic commentary notes:

There is no room in a free market for the non-player, the person who can’t “buy in”—the poor, the uninsured, the uninsurable. The special needs of the chronically ill, the disabled, infirm, aged, and the emotionally distressed are no longer valid claims to special attention. Rather, they are the occasion for higher premiums, more deductibles, or exclusion from enrollment. There is no economic justification for the extra time required to explain, counsel, comfort, and educate these patients and their families since these cost more than they return in revenue.

The “new health care environment” has, of course, deep cultural resonance with the affluent, inegalitarian society from which it springs. Supporters of medicine for profit do not hesitate to class their endeavor as part of the American Way: “Freedom of choice is valued more highly than equality of outcome, and . . . our commitments to beneficence are limited, as reflected by the absence of a constitutional right to receive welfare services. These we take to be the broad moral assumptions of American health care policy.”

Can we still hear, in this “new health care environment,” today’s prophetic voices? Unless we make our world a place free of structural violence, we cannot completely obliterate these voices. We can only ignore them, and we seem to be doing a rather good job on this score. But the experiences of those who are sick and poor—and, often enough, sick because they’re poor—remind us that inequalities of access and outcome constitute the chief drama of modern medicine. In an increasingly interconnected world, inequalities are both local and global, as examples from my own practice illustrate. These stories also ask us to decide whether or not we believe that health care is a basic human right.