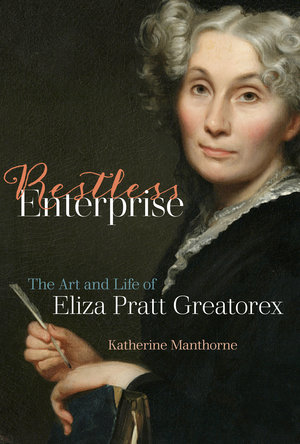

By Katherine Manthorne, author of Restless Enterprise: The Art and Life of Eliza Pratt Greatorex

This guest post is part of our #CAA2021 conference series. Visit our virtual exhibit to learn more.

Today human movement is at a record high. The United Nations reports that approximately one out of every seven people is an international or internal migrant, whether by choice or force. Numerous art exhibitions and publications examine the responses of 21st century artists to migration, immigration and displacement. Caught up in current turmoils, we tend to forget that the 19th century experienced its own seismic population shifts and waves of immigration that overwhelmed people and precipitated a diverse range of provocative and personal visual responses.

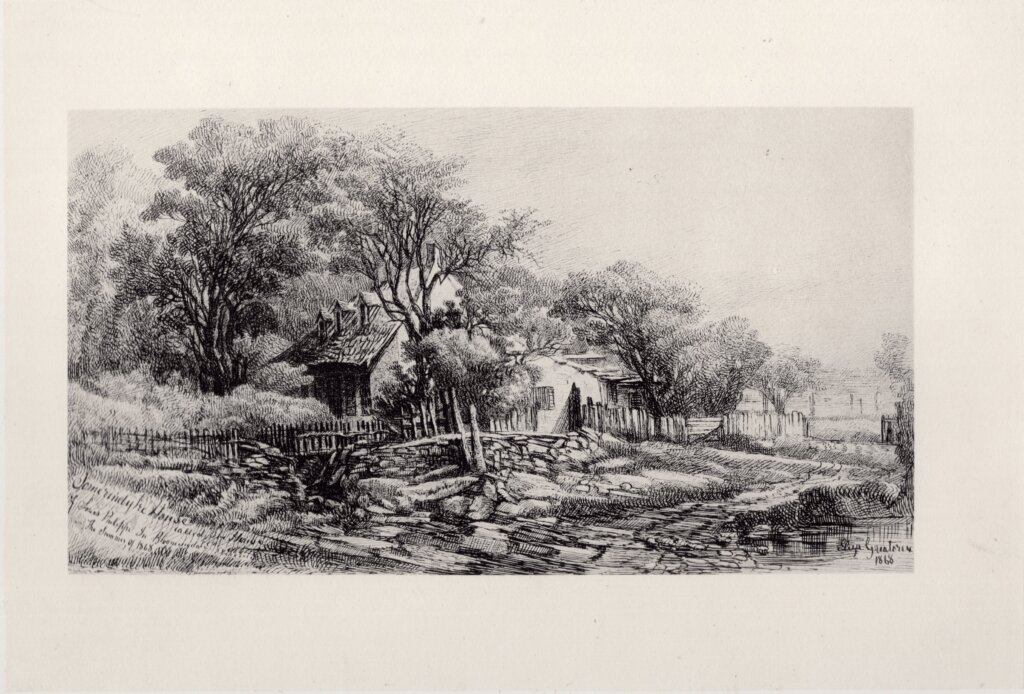

My new book Restless Enterprise: The Art and Life of Eliza Pratt Greatorex focuses on an Irish-born woman artist who left her native land during the Potato Famine in 1848 and headed for New York. Within ten years, Greatorex was a celebrated artist known for her Hudson River School-style paintings. Dislocation had become a way of life for this daughter of an itinerant Methodist minister who moved his wife and eight children annually to a succession of villages in the north of Ireland. Within a year of arriving in the U.S., she married musician and composer Henry Greatorex, whose performance schedule required a commuter marriage up and down the eastern seaboard and beyond. On an 1857 sojourn across the Atlantic, they visited their respective family homesteads that she captured on canvas (Fig. 1). She then stayed on in London while he sailed back to the U.S. for the concert season in Charleston, S.C., where he contracted yellow fever and passed away.

When the impractical Henry left Eliza with four children and no financial provisions, she formulated the rather improbable plan of becoming a landscape painter to support them. After a brief mourning period, with children in tow, she took up the life of the traveler artist whose itinerary embraced three years in Germany, a summer in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado, endless circumnavigation of Manhattan Island, a year in Morocco, and tours of Italy and Norway, all alternated with frequent interludes in France. They lived frugally, with mother and daughters teaching, illustrating, and selling artworks when they could.

Below: Katherine Manthorne gives a sneak peek inside Restless Enterprise

As an academic art historian, I aim for objectivity in my work and offer interpretations that I can support with documentary evidence. Although conventional wisdom has it that the recovery of nineteenth century women’s lives is usually dependent upon private diaries and correspondence, Greatorex did not oblige me in this way. Lacking written records of her personal insights, I was reluctant to indulge in speculation on her psychological state in my book. Now that the book has launched, however, I find myself pondering her status as a stranger in a foreign land, her lifelong peregrinations and string of rented apartments and studios, and how that translated into a pictorial focus on the motif of home.

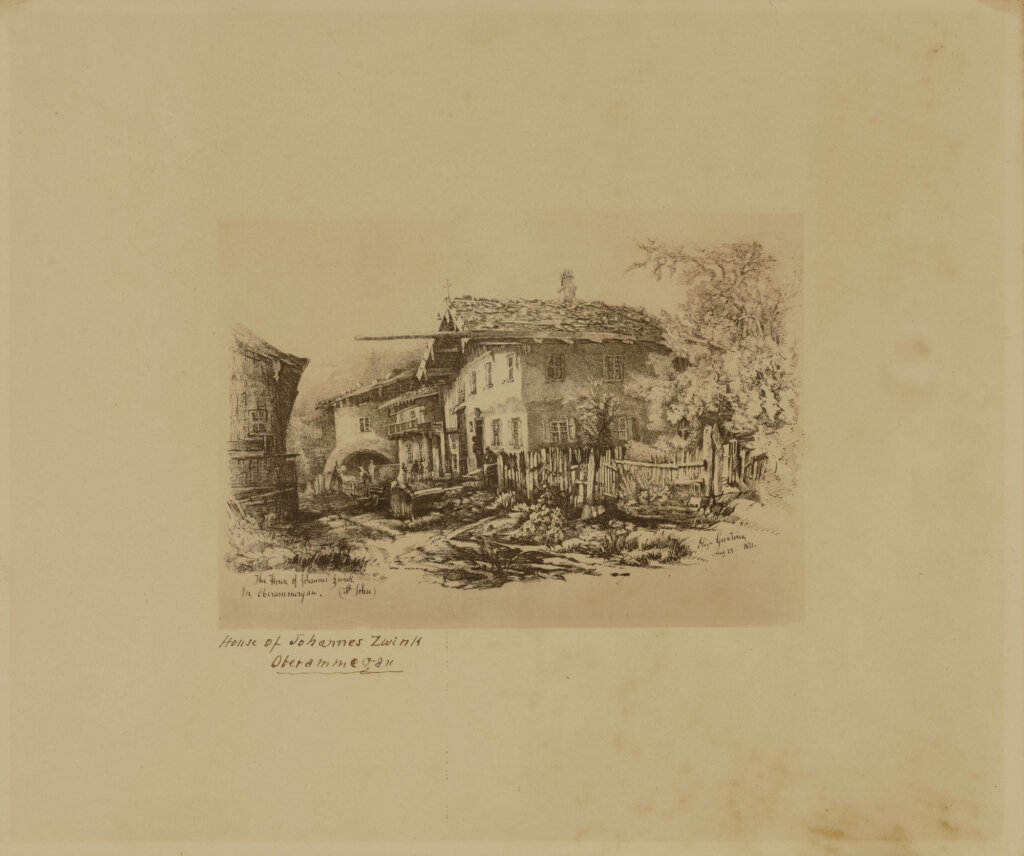

In 1871, Greatorex attended the Passion Play held once every ten years in Oberammergau, Bavaria, where she and her family spent the summer living amongst the townspeople who doubled as actors in the sacred drama. The village was swarming with artists from all over Europe and America, all of whom were capturing the theater, actors and visiting tourists. All but one that is. Greatorex instead created a series of pictures of the rustic home exteriors of the local players (Fig. 2) for her illustrated book The Homes of Oberammergau (1872).

Heading next to Colorado Springs, she and her daughters researched options for acquiring a ranch, but then contented themselves with pictures of camps, homesteads and newly formed towns in the barely settled western territories that appeared in her Summer Etchings in Colorado (1873). Returning to New York, the artist completed her campaign to depict the many estates of the established Knickerbocker families (Fig. 3), Dutch farms and churches that were being demolished to make way for modern structures in the post-Civil War building boom. Complementing the images was a text describing life within these walls: an elaborate lament on the loss of hearth and home. Reluctant to directly express personal pain, Eliza Greatorex instead wove a subtle commentary on immigration and the desire for belonging through her pictures of domestic dwellings both humble and grand.