Poetry can be powerful because it succinctly puts a voice to innermost feelings and can provide a dialogue for our experience, to process questions, anxieties, grief, anger, and optimism, so this National Poetry Month we’re turning to poetry for uncertain times.

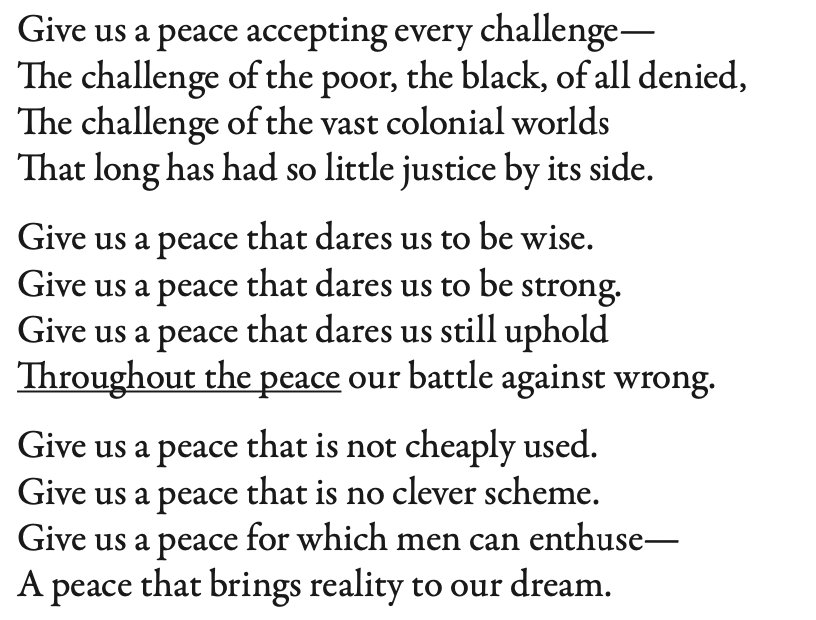

Langston Hughes, one of America’s greatest writers, was an innovator of jazz poetry and a leader of the Harlem Renaissance whose poems and plays resonate widely today. In Letters from Langston: From the Harlem Renaissance to the Red Scare and Beyond the letters between Hughes and four leftist confidants sheds vivid light on the poet’s life and politics. Hughes and his friends reveal their visions of a world without hunger, war, racism, and class oppression in an era of uncertainty. The following excerpt is from the poem “Give Us Our Peace” featured in “Chapter Six: World War II and Black Radical Organizing” and is addressed to Hughes’s friends Matt and Nebby Crawford. During this period, Hughes had also started the column “Here to Yonder” in the Chicago Defender, the nation’s largest Black weekly newspaper at the time.

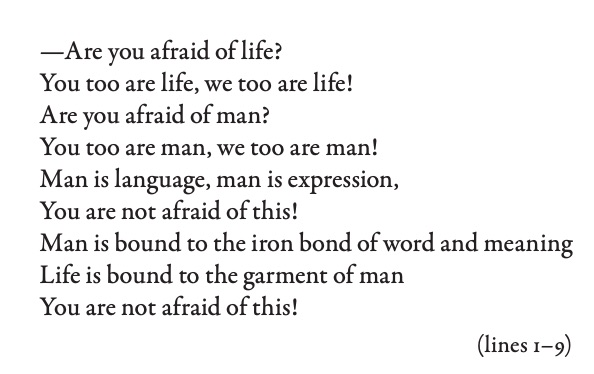

In I Too Have Some Dreams N.M. Rashed and Modernism in Urdu Poetry, A. Sean Pue I explores the work of Urdu’s renowned modernist poet, N. M. Rashed, whose career spans the last years of British India and the early decades of postcolonial South Asia. A. Sean Pue argues that Rashed’s poetry carved out a distinct role for literature in the maintenance of doubt, providing a platform for challenging the certainty of collective ideologies and opposing the evolving forms of empire and domination. Soon after India and Pakistan gained independence, Rashed articulated a theme of separation between word (arf) and meaning (maʿnī) that he reworked in a number of ways in his poems. This separation referred to the disconnection between state ideology and practice, particularly, if not exclusively, in the context of Pakistan. On the other, it signified a gap between human language and metaphysical meaning in general. His late poetry consistently challenges the certainty of conventional meanings and assertions, while also holding open the possibility of new ways of understanding the human subject and social life. He expresses this view most clearly in what has become one of his most popular poems, “Zindagī se arte ho?” (Are You Afraid of Life?)

In I Too Have Some Dreams N.M. Rashed and Modernism in Urdu Poetry, A. Sean Pue I explores the work of Urdu’s renowned modernist poet, N. M. Rashed, whose career spans the last years of British India and the early decades of postcolonial South Asia. A. Sean Pue argues that Rashed’s poetry carved out a distinct role for literature in the maintenance of doubt, providing a platform for challenging the certainty of collective ideologies and opposing the evolving forms of empire and domination. Soon after India and Pakistan gained independence, Rashed articulated a theme of separation between word (arf) and meaning (maʿnī) that he reworked in a number of ways in his poems. This separation referred to the disconnection between state ideology and practice, particularly, if not exclusively, in the context of Pakistan. On the other, it signified a gap between human language and metaphysical meaning in general. His late poetry consistently challenges the certainty of conventional meanings and assertions, while also holding open the possibility of new ways of understanding the human subject and social life. He expresses this view most clearly in what has become one of his most popular poems, “Zindagī se arte ho?” (Are You Afraid of Life?)

Dictée is the best-known work of the versatile and important Korean American artist Theresa Hak Kyung Cha. A classic work of autobiography that transcends the self, Dictée is the story of several women: the Korean revolutionary Yu Guan Soon, Joan of Arc, Demeter and Persephone, Cha’s mother Hyung Soon Huo (a Korean born in Manchuria to first-generation Korean exiles), and Cha herself. The elements that unite these women are suffering and the transcendence of suffering. The book is divided into nine parts structured around the Greek Muses. Cha deploys a variety of texts, documents, images, and forms of address and inquiry to explore issues of dislocation and the fragmentation of memory. Part novel, prose poem, biography, and photo book all at once, the result is a work of power, complexity, and enduring beauty.