This guest post is published as part of our blog series for the annual meeting of the American Historical Association, January 4-6 in New York. #AHA20

by Kris Lane, author of Potosí: The Silver City That Changed the World

Quincentennials, even when not celebrated, concentrate the mind. Native American activists led scholars, artists, and teachers in debating the meaning of 1492 nearly three decades ago, and many reverberations from that moment are still with us. State legislatures across the United States are currently replacing Columbus Day with Indigenous Peoples’ Day, or in the case of Oklahoma, combining the two. The half-century clock keeps turning. Last year marked the 500th anniversary of Cortés’s fateful march on Tenochtitlan, which has prompted soul-searching on both sides of the Atlantic and across the political spectrum. Should the present government of Spain apologize for Cortés and all that came after?

The public focus on “contact” and “conquest” as watershed events remains salient – every story needs a beginning – yet most historians urge observers of any anniversary to step back, zoom out, and take a deep breath in hopes of establishing a broader context and a longer timeline so as to not overstate or misjudge the meaning of a moment. It is a difficult and unpopular exercise. The emotional urge to commemorate is deeply rooted in most cultures, even if the call for remembrance is frequently a collective exercise in imagination, at times requiring a willful avoidance or even public denunciation of contrary evidence. These are history’s battlegrounds, and facing the term “conquest” requires that one side’s triumph must have been the other’s unequivocal tragedy. “Pivotal moment” narratives, like national origin stories, may be mobilized to seek justice and inclusion or their opposites.

One of the many consequences of 1492 (and of 1500, 1519, 1532, 1538, and so on) was the massive exploitation of gold and silver deposits in what is today Latin America. Precious metals extraction looms large throughout the region’s colonial and modern histories, yet for the most part these metals’ discovery does not bear a commemorative starting date to match the California Gold Rush’s “Eureka moment” at Sutter’s Mill in 1848. Mexico could claim dozens of such moments, as could Brazil or Colombia (to name a few), but if one great discovery – or claim of discovery – stands out it is that of the Cerro Rico of Potosí, a virtual mountain of silver whose revelation made world news and became a secular icon after an Andean prospector named Diego Gualpa struck pay dirt high on its flanks in 1545.

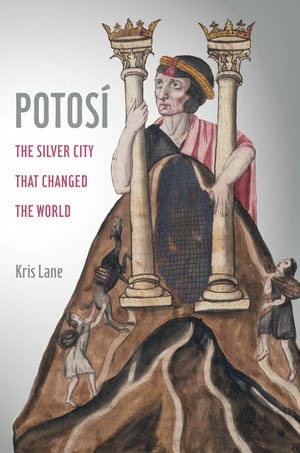

The Potosí quincentennial is still a ways off, but scholars and activists have had much to say about about this silver mountain and its adjacent city, the “Imperial Villa,” from the beginning. Cieza de León gave us the first indelible image of the Cerro Rico in 1553, copied in Antwerp, Amsterdam, London, Milan, and Istanbul.

With wonder came moral condemnation: Dominican friar Domingo de Santo Tomás famously labelled the Cerro Rico a “mouth of hell” in 1550.

The idea stuck, and soon the horrors of mine work in Potosí became stock images of the Black Legend thanks to engraver Theodor de Bry, who took his cues from José de Acosta’s Natural and Moral History of the Indies. Spain’s enemies and internal critics alike carried on through to independence denouncing the abuses of the infamous mita labor draft, scourge of every Habsburg and Bourbon monarch’s conscience. Simón Bolívar drove a stake into this vampire’s heart atop the Cerro Rico in 1825, but as one expects from the undead, new forms of exploitation replaced the mita.

In the early 1970s, Eduardo Galeano took a page from Las Casas (and Santo Tomás) to describe Potosí as the epitome of “five centuries of the pillage of a continent.” In this telling, the colonial period refused to end as the British, French, and Yankees simply picked up where the Spanish had left off, siphoning away the riches of Latin America to finance the industrial development of the global North, all accomplished through the shameless sacrifice of indigenous blood. Relying on Galeano, Potosí tour guides and many area residents will tell you today that more than 8 million native Andeans died working inside the Cerro Rico under Spanish rule alone. Galeano would later distance himself from the “Lascasian” polemic of Open Veins, but his original narrative – like Las Casas’s Brevísima – has endured, resonating far beyond Bolivia.

What then can be said about Potosí that both complicates and clarifies its nearly five-hundred year-old legacy? Instead of seeking to debunk myths or counter sermons with statistics, my book Potosí: The Silver City that Changed the World attempts to place this most prominent of the Americas’ numerous mining towns in a 360-degree global context, to accept its importance as a source for the raw material or “seeds” of global capitalism while also seeing it as something more than a tragedy, a site of colossal suffering and despair.

My hope is that by exploring the rich and growing historiography of Potosí alongside its nearly bottomless fund of primary sources, readers might gain a sense of the contradictory impulses that drove early modern history, not just in Spanish South America or within the Spanish Empire but around the globe. Like most things of significance, Potosí’s discovery spawned unintended consequences, some still evident, some having long since faded from view despite their importance. One largely forgotten legacy of the Potosí bonanza was the substantial flow of enslaved Africans into the Southern Cone after the 1580 annexation of Portugal. Their huge contribution to the histories and cultures of these regions has only barely been recognized. Another nearly forgotten consequence of bonanza was the massive influx of a dizzying variety of global consumer goods, turning the hardscrabble mining camp of Potosí into the undisputed warehouse and conspicuous consumption theater of the Andes.

The story of Potosí is at root the story of silver, like gold a globally transformative element freighted with contradictory meanings.

Narrating Potosí’s long history as opposed to fetishizing its discovery or some other moment entails grappling with big, sweeping trends as well as dead-ends, mistakes, and catastrophes. I describe, for example, how rising world demand for silver in both the commercial and political realms after 1492 fueled rapacious extraction as well as technical innovation and even indigenous capital accumulation. Locally, mining the Cerro Rico enabled social destruction as well as social climbing, gendered exploitation as well as gendered self-reliance. Globally, Potosí silver lubricated global exchange and encouraged the development of regional industries even as it prompted or pumped up the volume on the most deadly wars yet seen in human history.

Is the strange tale of Potosí a mostly Latin American story, as Galeano framed it nearly fifty years ago? Certainly we can continue to see it this way, but what we often forget as Latin Americanists is that Potosí shares the broader legacy of the Klondike and of California, of “Deadwood,” Ouro Prêto, the Colombian Chocó, and Chuquicamata. A lasting consequence of 1492 (and of 1519, 1848, and so on) is mining in the Americas, long cycles of hemispheric mineral extraction that began with Columbus and transformed (and continue to transform) the wider world. It is true that native Americans were adept miners and refiners long before the arrival of Europeans and Africans, but the nature and scale of mineral extraction changed radically after 1492. Potosí’s huge mining and refining complex helps us to envision this change and its consequences.

When we speak of justice and inclusion in Greater America, this globally entangled hemisphere of shared triumphs and tragedies, bonanzas and disasters, let us consider the complex and contradictory legacy of Potosí. In picking through its vast piles of historical detritus, its legends and representations, its scattered threads and traces, one may still find unexpected treasures that glint like truth.