John Vilanova and Kyle Cassidy’s article in the latest issue of the Journal of Popular Music Studies,“‘I’m Not the Drummer’s Girlfriend’: Merch Girls, Tour’s Misogynist Mythos, and the Gendered Dynamics of Live Music’s Backline Labor,” began life during a brainstorming session between two colleagues who wanted to use their collective experience in the creative industries to explore a different type of scholarly intervention. Beginning life as a creative art installation before becoming a journal article, “I’m Not the Drummer’s Girlfriend” explores the term “merch girl”—shorthand for a woman who sells merchandise at concerts—as a symptom of an industry rife with in-built sexism and inherently hostile to women seeking employment in live music. What begins as a contemporary analysis of the term through fieldwork and interviews with twenty merch sellers becomes a larger critique through a historical survey, which suggests “the road” is itself a gendered space and that addressing endemic sexism thus requires more thoroughgoing solutions.

Here, the co-authors discuss the conception, findings, and creative opportunities the project invited.

John Vilanova: I know for me, this project felt like an opportunity to drill down on something specific—this term, “merch girl,” that had always vexed me. What was your goal in doing this?

Kyle Cassidy: A few years ago I started working on a book project with another creative colleague, Cat Mihos, about roadies—people who tour professionally. Cat has been on road crews her entire adult life, with huge acts like Mötley Crüe, Lady Gaga and the Jonas Brothers, and that project laid the groundwork for this one. But in general, I am fascinated by the apparatus which makes the music happen: I photographed some of the road crew for Beyoncé Knowles and it was literally a village of tour busses and so many people in the crew that you could not possibly know them all. And on the other hand, I have photographed bands that have one person touring with them who is doing the driving, the videotaping, the teardown, and the merch. So just this whole gamut of what is required to make the record happen live is just absolutely fascinating to me—and then on top of that to try and amplify the voices of people who may not have access to the same range of ears that I do.

JV: Totally. I think one of the things I wanted to get at is that people do not typically think of the concert venue or the tour bus as a workplace, but that there are pretty defined roles, job descriptions, and expectations. This was one of them that was illustrative of many of the dynamics we wanted to visibilize, and it was great to use the network you had been building to source interlocutors. And you eventually posted on Facebook searching for interviewees, which spawned the paper’s titular insight . . . .

KC: Yes—between working on this roadie project for a couple of years, having photographed a lot of bands and album covers, and having my photos on an enormous amount of merch, I figured I probably had a critical mass of merchers amongst my Facebook friends so I just posted that we were looking to interview people who sold merch at shows. And one of the first comments was from a man who’s actually a touring musician who said, “Don’t you mean the drummer’s girlfriend?” And that post just lit up with really angry and annoyed people, mostly women, responding to him along the lines of “I’m working extremely hard to be taken seriously as a professional and this is absolutely the kind of crap that we do not need.” That was an extremely important moment for me in understanding how all of this worked. I knew for sure from my own experience that women typically have a much more difficult time on the road than men do and here was an instantaneous example of someone who I’m sure didn’t mean to make a sexist remark saying something casually that served to entrench that stigma and make women’s lives even more difficult on the road.

JV: Right. He thought he was being funny, but it was of course so pointed and in this context so unbelievably damaging. That was one of the things that jumped out to me: In addition to the egregious examples the interlocutors we started to meet shared with us, there was an everydayness to the misogyny they described that they could articulate that we wouldn’t immediately see: Being a woman on the road contains within it a web of misogyny that even the most engaged male allies might initially miss.

KC: I thought the story one of our interlocutors shared with us about asking to be handed something and getting a patronizing response made that clear.

JV: Right! The very act of carrying things—which feels like a huge percentage of life on the road—was always gendered for these people. And we wanted to kind of represent the spatial, material, and lived aspects of all this stuff, which felt like it could be done with more than just a run-of-the-mill PowerPoint.

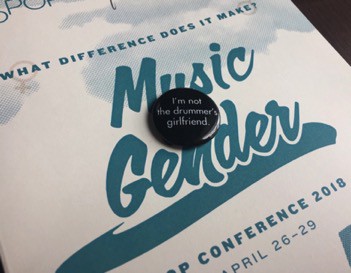

KC: I’ve been to a lot of conferences and I know how…easy it is to do a less than memorable presentation. It felt like one way to drive this home and to illustrate some of those aspects was to do something over-the-top so as to be memorable. I’d done all this photography of merch people and their setups so somewhere along the line, we decided to make our own merch table, make merch with our photos, and just pop it up in the back of the lecture hall as a kind of exhibition. So we made buttons that said “I’m Not the Drummer’s Girlfriend” and we made t-shirts with alternate names for the position that our interviewees had suggested like “Cotton Slinger,” “Merchandizer,” and things like that. Coupled with fake records with photos of merch people and their quotes, we celebrated the position as if it was the headlining act itself.

JV: Right. And we proposed that idea as a creative submission for the Pop Conference at MoPOP in Seattle in 2018: To install a pseudo-merch stand at the museum. Originally, we even conceived of it being up all weekend for people to sign up for our fake “Street Team” and collect buttons. The theme in the call that year—“What Difference Does It Make? Music and Gender”—felt like an opportunity for research that emphasized the in-built misogynies contained within the music industry, and emphasizing touring as a workplace that had its own specific gender roles, standards, and expectations. While I was composing the presentation we’d do along with the stand, you did a lot of the graphic design. Take us through the planning of that.

KC: I miss the record album—I don’t miss the difficulty of listening to the music, but I miss the large-format, tangible graphic that goes with a record album. You not only get the music, but you get a nice photograph of the band and maybe the lyrics on the back, so that just seemed like a good way to show off the images we had. And we ordered the buttons from an actual rock band merch company.

JV: I’m very proud of the buttons; it feels like they take something lots of people in these spaces wear in that style of button but make it a political and pedagogical intervention of sorts. And the response we got was pretty overwhelming, as the many women in our audience suggested we were really getting at a dynamic that was known but not talked about enough. Then, during the conference keynote panel, Sub Pop Records’s CEO Megan Jasper, while talking about participating in live music, said—totally unaware of our project—that she “could’ve been someone’s girlfriend, but she wanted more than that” out of being involved in the live touring industry. With that, it really felt like this “girlfriend” expectation was so key to the presumptuous ways women were seen at concerts. It was assumed to be their entire reason for being there in the first place.

KC: If you’ve never been to the Museum of Popular Culture, they have a screen that must be forty feet wide and that’s what we were showing our PowerPoints on. It was pretty amazing.

JV: Then afterwards, we conducted more interviews and began building out the framework as an article for submission. What was fascinating about it was that it began to feel like the only way to review the “literature” was to do a kind of wide-ranging one that of course talked about “groupies” and their fraught history, but that what we were actually situating our interlocutors’ comments within a longer history of the road itself, which had always been a space gendered male. This went as far back as Homer’s Odyssey with the Sirens, Robert Louis Stevenson, and the early American songbook. It showed how deeply these ideas about this mode of movement and labor went.

KC: What’s the path out of this? How do we as music consumers and people who go to see live music fix this problem?

JV: I’m grateful that we were able to offer some ways of addressing these inequalities, most of which came directly from our incredible interlocutors and which ranged from the very practical ways to make their jobs easier (“Bring $1s or $5s to the show if you plan to pay cash for merch”) to the more structural questions, such as asking how to have things like HR departments or accountability measures for more contingent labor. In the end, merch is more important than ever, which meant it was more necessary than ever to share this work and hopefully make an intervention.

We’re pleased to make the article, “‘I’m Not the Drummer’s Girlfriend’: Merch Girls, Tour’s Misogynist Mythos, and the Gendered Dynamics of Live Music’s Backline Labor,” free to read for a limited time.