By Celeste Watkins-Hayes, author of Remaking a Life: How Women Living with HIV/AIDS Confront Inequality

This guest post is part of our ASA blog series published in conjunction with the meeting of the American Sociological Association in New York City, NY, August 10-13. #ASA19

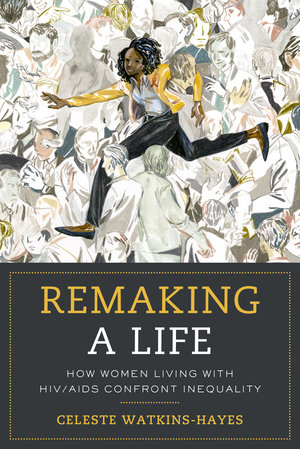

Starting in 2005, I began documenting the lives of almost 200 HIV activists, advocates, policy officials, and women living with HIV/AIDS in Chicago and other U.S. cities. I found something unexpected—a story about the profound power of personal and political transformation that can emerge when safety nets protect our most vulnerable. I chronicle this in my new book Remaking a Life: How Women Living with HIV/AIDS Confront Inequality.

I introduce readers to women from a variety of backgrounds, but unequivocally demonstrate that HIV/AIDS is an epidemic fueled by intersectional inequality. Many of the women interviewed were dealing with a panoply of crushing obstacles before their diagnoses: poverty, drug addiction, sex work, and a lack of social services, all of which make the transmission of HIV more likely.

But once women received much-needed access to health care; housing; as well as economic, social, and political capital, many were able to move beyond the devastation of their diagnoses and to follow a trajectory that took them from dying from to living with to even thriving despite HIV and other injuries of inequality. I document the history of the HIV safety net and the role of women in advocating for services that address their unique needs, thereby expanding how many understand the face of HIV/AIDS activism. My book also grapples with the perverse irony that it took an HIV diagnosis for these women to gain access to the help they always needed, and in the process, it offers a scathing indictment of our now-tattered social safety net that leaves so many to fend for themselves.

In communities around the world, there are women whose lives are remarkably similar to those of the women I met while writing this book. They are stigmatized because of some undesirable social characteristic, deemed unworthy and undeserving of our care and concern. Their lives may have been relatively stable before the crisis arrived. Or they may have suffered from a host of physical, emotional, and economic traumas. While some may be tempted to disregard these women or ignore their potential, it would be foolhardy to do so. We lose valuable political voices, mothers to children, partners to those looking for loving relationships, and teachers to those of us trying to understand important issues. We lose valuable members of our nation and even the world when we chose to ignore, stereotype, or reduce women to the circumstances they face or the choices they make, especially when those choices are so limited. Many of the personal and political transformations that I capture in my book benefit the greater good, and those contributions would be lost without the courage of women who move from marginalization to meaning.

My book does not downplay or romanticize the devastation of the HIV epidemic or the other struggles women are facing. Rather, it documents the social process by which women take those circumstances and reinvent themselves through the support of effective safety nets comprised of people, institutions, and policies that help women to remake their lives. In the process, women develop new tools and strategies to cope with and confront injuries of inequality, and they embody the theme for the 2019 ASA meetings, “Engaging Social Justice for a Better World.”