We are deeply saddened to hear of Yale Senior Research Scholar and true giant in the fields of sociology, economics, and world systems analysis Immanuel Watterstein’s passing at age 88. Wallerstein’s highly influential, multivolume opus, The Modern World-System I, II, III, and IV, is one of this century’s greatest works of social science. An innovative, panoramic reinterpretation of global history, it traces the emergence and development of the modern world from the sixteenth to the twentieth century.

In the following UC Press Blog post first published in 2017, Scott Kurashige reflects on the anniversary of a key event relating to Wallerstein that shaped the thinking behind his book, The Fifty-Year Rebellion: How the U.S. Political Crisis began in Detroit.

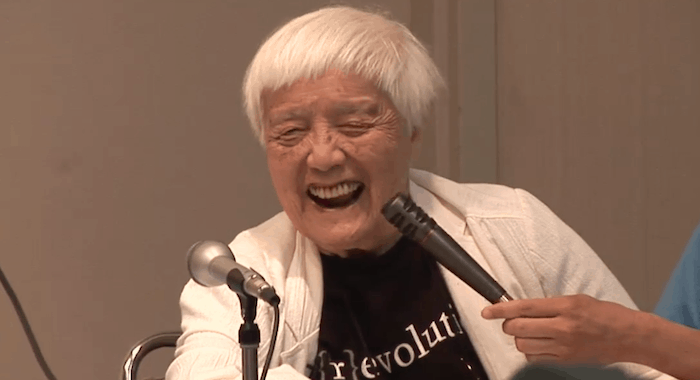

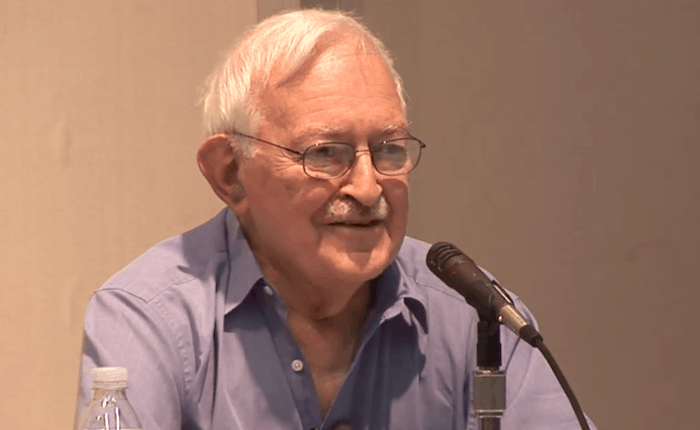

Grace Lee Boggs & Immanuel Wallerstein: A Dialogue Between Two Visionaries

One of the greatest honors in my life was the opportunity to moderate a historic conversation between the renowned historical sociologist, Immanuel Wallerstein, and the late philosopher-activist, Grace Lee Boggs (1915-2015). It took place in Detroit on June 24, 2010, before a boisterous crowd of seven hundred people during the United States Social Forum.

The recorded conversation gives a sense of the visionary quality of these radical and profound thinkers. Long before Brexit, Trump, Corbyn, and Sanders made headlines, Wallerstein addressed the rise of “right-wing populism” and “electoral fluctuations.” Quoting Hegel, Boggs implored the audience to think dialectically about the volatile times we live in. Because progress does not occur in a “straight line,” we must accept the challenge “to use the negative as a way to advance the positive.” Their phenomenal exchanges are a wonderful place to start as we try to make sense of the economic, political, and epistemological crises we face in 2017.

Surveying the grand sweep of history, Wallerstein reminded us that “historical systems do not go on forever.” While it undoubtedly caused immense suffering and exploitation, the capitalist system had functioned well on its own terms for decades but “has moved far away from equilibrium and gotten into what we call a structural crisis.” When a system is stable it takes a tremendous amount of force to move it slightly in one direction or the other. However, once a system is out of equilibrium, the “free will factor” becomes paramount. Thus, we are currently locked in a struggle to determine whether capitalism will be replaced over the next three to four decades by a relatively more egalitarian and democratic system or a more oppressive system that is even worse than what we have known.

“It’s a fantastic period,” Boggs emphasized, because we are at “that time on the clock of the universe where we face our evolution to a higher humanity or the devastation and the extinction of all life on earth.” Detroit, she asserted, is the ideal place to witness the devastation of racism and deindustrialization alongside the rise of grassroots movements that are making the city “the national and international symbol of a new kind of society.”

The following are excerpts from the edited transcript, which was published in the updated and expanded edition of The Next American Revolution: Sustainable Activism for the Twenty-First Century.

IMMANUEL WALLERSTEIN: We’re in a depression. People don’t want to use the word, as though not using the word will wash it away. We’re in a situation where the choices are impossible because the fluctuations of the world market are so radical that it’s impossible in a very short run to predict…. When they can’t make short run rational decisions, they panic. Individuals panic, capitalists panic, all sorts of people panic.

If you want to understand right-wing populism in the United States—or, indeed, in Europe or in other parts of the world today—understand it in terms of people panicking. They don’t know how to protect themselves. They do see that they’re in a shaky situation, and they lash out at whatever. That leads to xenophobia: you find the enemy and attack it in a way that doesn’t solve any of your problems, but it makes you feel better for a few minutes—until the next time that it doesn’t work.

That also explains electoral fluctuations, which have been tremendous in the last few years. Everybody knows Spain is in trouble, right? It’s got too much debt and so forth and so on. And everybody’s been telling Spain, the government, that what you’ve got to do is cut down your expenses, cut your budgets, and so forth. The Spanish parliament voted the severest cuts in the history of Spain. The very next day the Fitch ratings downgraded Spain’s bonds. And the argument—they gave it in writing—was that cutting the budget reduces the possibility of growth, which it does.But there it is: damned if you do, damned if you don’t. If you don’t do it, you’re damned because you’re a spendthrift and allowing the budget to get out of hand. And if you do do it, you’re cutting the possibility of growth. Well, what do you do if you’re a government? There isn’t any good thing to do, and that’s what virtually all the governments of the world today are facing. They don’t have a good choice. Whatever they chose, it’s “damned if you do and damned if you don’t.” It’s a losing game, and voters blame them. Well, they’ve got to blame somebody, and they blame the government in power. And they vote somebody else into power, who does what? They’re faced with the same impossible choices. That’s the present situation in the world.

GRACE LEE BOGGS: I think we need to understand why the World Social Forum began in the first place. It began after the Battle of Seattle. You remember when fifty thousand people came out—Teamsters, Steelworkers, women, young people—and they shut down the WTO [World Trade Organization]. Within a couple of years the World Social Forum began at Porto Alegre, announcing “Another world is necessary, Another world is possible.” But participants weren’t quite clear about where this other world was happening.

That’s why I want folks to read the commentaries that Wallerstein puts out every couple of weeks. Because they help you understand that it [the failure of U.S. foreign policy] is not only about Obama being weak; he may be. It’s not only about [General David] Petraeus being ambitious; he may be. It’s about how the whole thing has become dysfunctional. And what do you do when something has become dysfunctional? Do you keep demonstrating and hoping that it becomes more functional? Or do you begin projecting and creating alternatives? And where do you look for these alternatives? You look for these alternatives among ordinary people who are trying to satisfy very basic human needs—needs for food, the need to know where you are in the world, the need to reassert your human identity….

How do we transform education to create a more participatory democracy? Representative democracy emerged a couple hundred years ago with the nation-state. We’re now in the period when there are a lot of questions about the nation-state. What is the nation-state? What is its relationship to the world? And we have a version of democracy, which is obviously dysfunctional in Washington and elsewhere in the world. So we are challenged to create another democracy, and I believe it can begin on the school level. We can start at kindergarten to involve parents and teachers and children in this other education that is possible. The role that labor played in building the movements of the Thirties is now being played by the people involved in education. And that involves parents, teachers, and children because education is the creation of human beings. What’s important to us today is not the manufacture of things as much as it is the creation of people.

Watch the full conversation below: