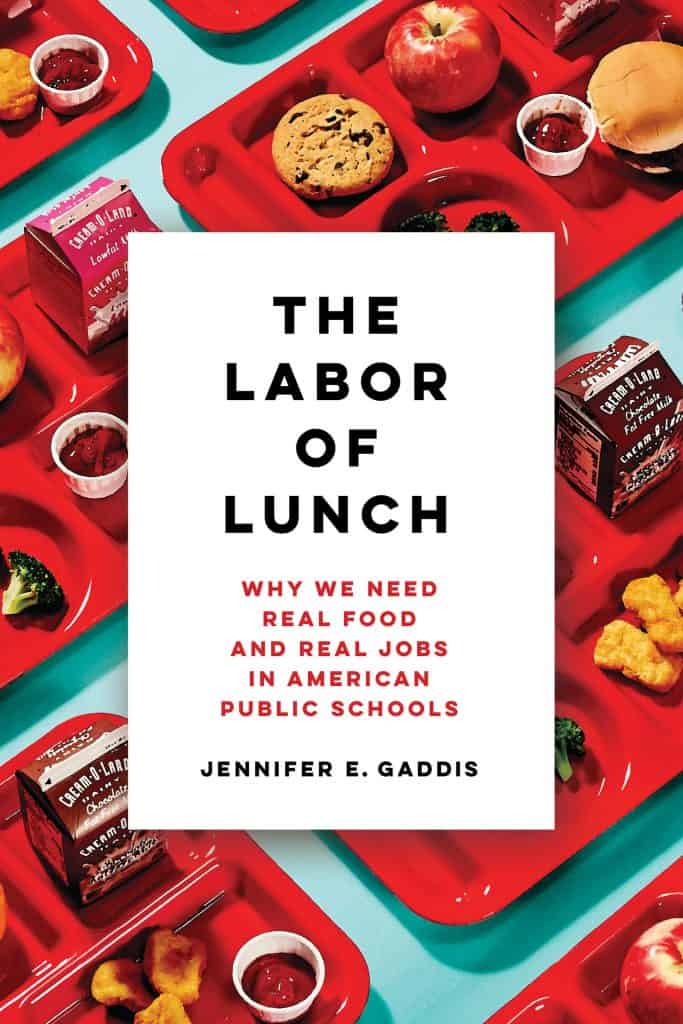

As California joins other states in seeking to end lunch shaming through legislation, the conversation turns importantly towards a national solution. Jennifer E. Gaddis’s timely new book, The Labor of Lunch: Why We Need Real Food and Real Jobs in American Public Schools (publishing in November), is a stirring call to action and a blueprint for school lunch reform capable of delivering a healthier, more equitable, caring, and sustainable future.

Excerpt from Chapter Four: Cafeteria Workers in the “Prison of Love”

For the real food movement to advance food justice in American K–12 schools, kitchen and cafeteria workers must take center stage. Like the many women laboring away in home kitchens, their work often goes unnoticed and under-appreciated, yet they provide tremendous value to society by raising and caring for children. Real food, as I’ve come to understand it, is about more than just ingredients. It’s also about respect for those who grow, process, cook, and serve the food and the relationships children form with those who feed them. We have a long way to go. But the first step is learning about what it’s actually like to be a lunch lady and what this job could be if we were to, in the words of my UNITE HERE colleagues, “respect the food” and “respect the lunch ladies.”

One way to respect these workers is to create the conditions for them to care well. Too often, the National School Lunch Program’s (NSLP) model of free, reduced-price, and full-price lunches causes workers to dole out care on a limited basis. Cafeteria workers use personal identification numbers to look up children’s eligibility for free, reduced-price, and full-price school lunches and to check the balance of the personal accounts that children’s caretakers fill with lunch money. During my fieldwork at an elementary school in Louisiana, a very small girl, probably in the first or second grade, walked past a cashier without paying. “Helloooo! Give me your number!” the cashier yelled after her. The little girl walked back to where she was sitting. “What is your number?” the cashier asked. The girl didn’t answer. “What is your number?” The cashier asked again. Still no answer. “What is your number?” Again, no answer. Maybe the girl had forgotten the lunch identification number she had been assigned at the beginning of the year. Or maybe she didn’t qualify for free lunch and knew she had accrued enough lunch debt to be denied a hot meal.

In many schools across the country, students with too much lunch debt are refused service entirely, given an identifiably inferior, stigmatized lunch—like a cold cheese sandwich—or subjected to the public humiliation of having their entire meal torn from their hands and dumped into the garbage. The practice, in its multiple forms, is known as “lunch shaming.” The little girl in Louisiana was all too familiar with this policy for managing lunch debt. It’s why she responded to the cashier’s multiple requests for her identification number by keeping her head down, her mouth shut, and her hands clutched tightly on her tray. She was hoping for the best and, this time, she got it. After what felt to me like a minute of paralysis—and likely much longer to the little girl—the cashier sighed, said “All right,” and let her take the tray of food without ever giving her identification number. The little girl never paid for the lunch. If it had been a manager, not just a university researcher observing this standoff, the sympathetic cashier would have been reprimanded—and possibly fired—for what technically amounts to stealing. Such harsh punishments are meted out in order to discourage frontline workers from shirking their duty to enforce the lunch-shaming policies set by their district supervisors.

This expectation that frontline workers deny food to children based on their financial standing detracts from the ethos of care and conviviality that many real food advocates hope to cultivate through garden and cooking classes. In the school I visited in Louisiana, for example, the real food initiatives sponsored by nonprofit organizations seemed to operate parallel to the NSLP. The nonprofit staff and volunteers provided experiential food- and garden-based education opportunities for the students and sought to elevate the culture of the cafeteria. During my visit in March 2013, student artwork decorated the walls of the cafeteria. A vase filled with fresh, student-grown flowers and brightly colored table linens added cheer to each table. But none of these efforts to “fix” school lunch changed the fact that the cashier—in a school foodservice operation outsourced to Aramark—was stuck serving cheap factory-made food and denying service to those who either didn’t qualify for free lunches or couldn’t afford to pay.

* * * *

Cafeteria workers, or lunch ladies, as they’re generally called, are often portrayed as punch lines or scapegoats. It’s politically convenient for anyone wishing to blame these workers for the systemic failings of the NSLP or the poor quality of “government programs.” But it’s not their fault. The budgets constraining school lunch programs are usually set by federal, state, and local policymakers who rarely, if ever, come face to face with the labor of lunch in school kitchens and cafeterias.