This guest post is part of our ASC blog series published in conjunction with the meeting of the American Society of Criminology in San Francisco, CA, November 13-16.

By Joseph O. Baker and Christopher D. Bader, authors of Deviance Management: Insiders, Outsiders, Hiders, and Drifters

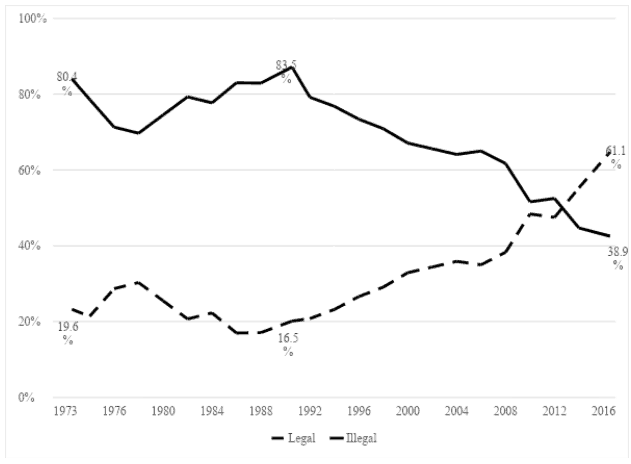

Changes to state laws in the U.S. regarding the medicinal and recreational uses of cannabis are one of the most interesting topics to consider for the study of politics, crime, and law. How is it that a Schedule 1 drug has gone from complete prohibition to medicinal use in most American states, and legalized recreational use in others? The answer, in short, is that the American public has changed its mind about cannabis (see the figure below).

FIGURE 6.1. Americans’ Attitudes Toward Marijuana Legalization (Source: 1973–2016 General Social Surveys)

But this only begs the obvious follow-up question: How does public opinion about a drug change so rapidly? Both historical and contemporary data can help us answer this question.

Historically, the repeal of alcohol Prohibition in the United States with the passage of the 21st Amendment offers a historical “experiment” pointing toward successful framing strategies for a normalization movement. In particular, the work of the Women’s Organization for National Prohibition Reform (WONPR), led by the ingenious and charismatic Pauline Morton Sabin, provides a template for the successful retraction of harsh penal codes governing the production, distribution, and consumption of a drug, at least in the context of representative democracies.

Sabin was able to achieve the repeal of the 18th Amendment in just over four short years, starting with the founding of the WONPR in May of 1929 and the culminating the ratification of the 21st Amendment in December of 1933. To see how she was able to pull off such an astounding feat of public persuasion and legislative maneuvering, we analyzed over 150 articles from the New York Times featuring Sabin and the WONPR across that time span. Using Walter Fischer’s narrative paradigm, we focused on how Sabin was able to accomplish both narrative fidelity (sense of affinity with an audience) and narrative coherence (acceptance of the story within existing cultural frameworks) for the cause of repeal.

Sabin used a two-pronged approach to achieve narrative fidelity and coherence for repeal, successfully pushing both public opinion and politicians toward the (re)normalization of alcohol. First, Sabin staffed the leadership of her organization, at both the national and state levels, with people from the highest reaches of society. The leaders of the WONPR were of high social class, intelligent and persuasive, and connected to powerful leaders in both politics and business. This allowed Sabin to refute claims that the WONPR were, to choose but a single colorful example, nothing more than “Bacchantian maidens parching for wine.” By choosing leaders with extremely high amounts of accumulated social capital, Sabin simultaneously insulated the organization from slander and positioned her members to have ready access to the halls of power.

Second, Sabin copied the organizational strategies of the most successful pro-Prohibition special interest group, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, using local organizing campaigns and membership drives. In essence, Sabin balanced the elite status of the WONPR’s leaders with grassroots membership. She also sought and brokered connections with a wide range of social organizations from all aspects of civil society, including but not limited to the American Federation of Labor, the American Legion, the American Medical Association, the American Bar Association, and numerous organizations in the business community.

Coupled with this organizational strategy, Sabin framed Prohibition repeal as more moral than Prohibition itself. The necessity of such a framework cannot be overstated, although convincing the wider public of the narrative coherence of such claims is certainly easier said than done. Sabin did this by pointing to the myriad of social ills caused by Prohibition enforcement, including organized crime capitalizing on vast black markets and the dangers of unregulated alcohol production and consumption.

Although Senator Morris Sheppard would famously say in 1930 that “There is as much of a chance of repealing the eighteenth amendment as there is for a humming bird to fly to the planet Mars with the Washington Monument tied to its tail,” precisely that fate awaited the 18th Amendment just two years later. When the WONPR held its third annual conference in Washington, D.C. in April of 1932, Sabin had leaders from each state chapter call upon their respective congressional representatives to deliver their message of repeal in person (see image below). The next day Sabin testified before the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee about legal paths to repeal, flanked by a contingent of WONPR leaders.

PHOTO: Delegates to the convention of the Women’s Organization for National Prohibition Reform gather in front of the Capitol Building for a group photo in Washington, D.C., April 13, 1932. The W.O.N.P.R. delegation is on hand to call on their representatives and senators to repeal the dry law. (Original caption. Source: AP Photo ID: 320413012)

While there are many differences between the repeal of Prohibition and the normalization of cannabis, there are also enough similarities that comparative analysis is instructive. To look at patterns in the legal status of cannabis across American states, we switched from qualitative analysis to quantitative analysis, using the legal status of cannabis in a state (prohibition, medical use only, and both medical and recreational use) as the outcome. Looking at the attributes of states that strongly and significantly predicted the legal status of cannabis in 2018, we found that there were three critical factors. In order of strength, they were: public opinion (among teenagers) about the dangers or cannabis, the percent in a state who self-identified as conservative Protestants (negative effect), and whether a state has direct democracy mechanisms allowing the public to vote on legislative statutes.

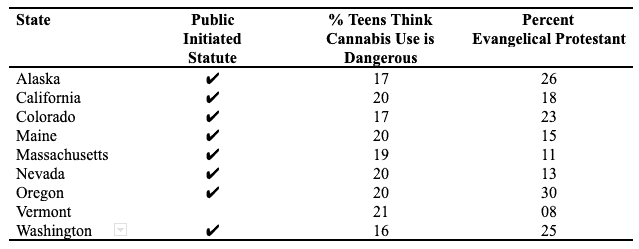

This tells us two important things. First, public opinion is indeed the key to legal change. In none of the states with recreational cannabis did more than 20% of teenagers—the next generation of voters—report that occasional cannabis use was dangerous. Further, such change is understandably facilitated by direct democracy, as all states that legalized recreational use other than Vermont had direct initiative statutes. Second, just as was the case in Prohibition, the strength of the central opponent—who in both cases was conservative Protestants—also plays an important role in whether normalization occurs. All states that have legalized recreational cannabis use have fewer than 30% of residents who are conservative Protestants (see the table below).

TABLE 6.1. Attributes of States That Had Recreational Marijuana in 2018

Sources: Ballotpedia for public initiated statutes; 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health for percent of kids who think occasional cannabis use is dangerous; 2007 Pew Religious Landscape Survey for percent evangelical Protestant

Both case studies point to the importance of public opinion in changing the legal status of a disputed drug. Both cases also point to the importance of political influence exerted by conservative Christianity. More importantly, the WONPR and Pauline Sabin offer a roadmap outlining effective public framing, mobilization, and legal tactics that normalization movements can use. Next time you raise a toast, perhaps it should be to her. And if you happen to care about cannabis reform, study up.

We delve more deeply into these issues, both theoretically and empirically, in Deviance Management. Suffice it to say that both history and contemporary data have a great deal to say about how and when normalization movements are successful. Cheers!