This guest post is published as part of our blog series related to the annual meetings of the American Academy of Religion & Society for Biblical Literature November 23-26 in San Diego. #aarsbl19

By Maria E. Doerfler, author of Jephthah’s Daughter, Sarah’s Son: The Death of Children in Late Antiquity

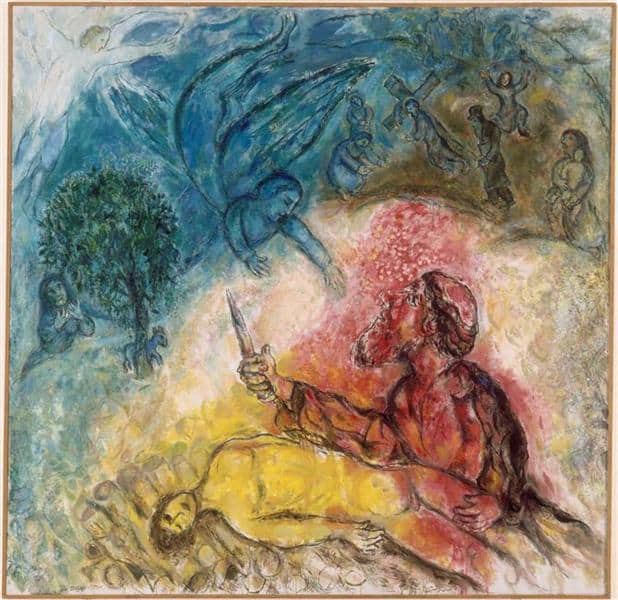

One of the most famous depictions of the Akedah, the so-called “sacrifice of Isaac” in Genesis 22, is Marc Chagall’s eponymous painting. Resplendent in reds, blues, and yellows, the painting puts before its viewer the familiar story: there is Abraham, brandishing the knife over the body of Isaac, splayed before him. There is the angel, hovering over the patriarch, while in the upper right corner muted sepia tones point ahead through time to Jesus’s crucifixion – an intertext both Chagall and countless interpreters before him thought to recognize in the text. There is even a ram, ready to become the substitute sacrifice.

Yet last summer, when viewing the work in person for the first time, my gaze was drawn to another figure, hiding in the shadows at the very edge of the painting. There, gazing at the scene from its periphery stands a woman: Sarah, Isaac’s mother. Her hands are raised in supplication or horror; her eyes, like Abraham’s, lifted to the angel. Sarah’s presence at the scene is the product of Chagall’s imagination; there is no counterpart for it in the biblical narrative—an absence that Phyllis Trible has called “the sacrifice of Sarah.” (1) Removed both from Abraham’s encounter with the divine and from her son’s side at a time of profound terror, the Hebrew Scriptures deny Sarah her place as both parent and partner. Chagall, unlike many artists, takes notice of her; and yet even his restitution of Sarah to the scene of the Akedah leaves her hovering at its margins.

Christian interpreters in late antiquity similarly wrestled with Sarah’s absence from the biblical text, at times wondering at Abraham’s ability to remove a son from his mother’s care without comment, at times imagining scenarios that might have justified such evasion. And yet, in many of these texts, Sarah returns to the scene of the sacrifice, or, in any case, receives her own part in the events surrounding it. One anonymous Syriac verse-homily from the fifth century, for example, envisions Abraham’s return home from the successfully averted sacrifice. There, he meets Sarah, who has long suspected her husband’s purpose, and tells her that her worst fears have been realised: Isaac is dead. Abraham’s deceit, intended to test Sarah, issues in a soliloquy of mourning: “I wish I were an eagle or had the speed of a turtle-dove,” the poet has Sarah proclaim,

so that I might go and behold that place, where my only child, my beloved, was sacrificed!

That I might see the place of his ashes, and look on the place of his binding,

and bring back a little of his blood to be comforted by its smell.

[That] I had some of his hair to place somewhere inside my clothes,

and when grief overcame me, I had some of his clothes,

so that I might imagine him, as I put them in front of my eyes;

and when suffering sorrow overcame me I gained relief through gazing upon them

I wish I could see his pyre and the place where his bones were burnt

and could bring a little of his ashes and gaze on them always, and be comforted. (2)

Sarah’s grief here is both blazing recrimination against her god, who has demanded the death her child, and her husband, who has aided and abetted the killing. The poet responsible for giving voice to her grief and anger put Sarah’s words at the disposal of Christian communities that had much need for mourning: in a period where as many as half of all children died before their tenth birthday, the laments of biblical figures, imagined and executed by homilist and hymnodists, could give voice to the suffering with which families and communities experienced the loss of a loved one.

In the Western world of the twenty-first century, by contrast, these voices have largely disappeared from view – and with them a formidable tool of lament. Mourning, ancient writers knew, was a powerful force. It could unmake a person, but it could also unmake a nation, halt wars, and change the minds of powers, both human and divine. In the present, in a country, where thousands of migrant children have been separated from their parents or caregivers, Sarah’s grief speaks in different voices to new contexts. In communities where gun violence claims the lives of teenagers on a daily basis, her lament must move to the center of the picture. In a world where children’s race, sexual orientation, and gender identity threaten their safety, the power that lies in mourning, in proclaiming and decrying suffering, in hollering at leaders and deities, finds new resonance. The voices of biblical characters, refracted through the readings of their late ancient exegetes open up vistas of emotions, harnessed for transformation. The task of the historian, like that of the artist, is to make them visible for a new era.

- Phyllis Trible, “Genesis 22: The Sacrifice of Sarah,” in Not in Heaven: Coherence and Complexity in Biblical Narrative, ed. Jason P. Rosenblatt (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991), 170-91.

- B.L. Add. 17206, lines 113-22, in Sebastian Brock, “Two Syriac Verse Homilies on the Binding of Isaac,” Le Muséon 99.1-2 (1986): 61-129, at 121-2, translation in Sebastian Brock, Sebastian Brock, Treasure-house of Mysteries: Explorations of the Sacred Text through Poetry in the Syriac Tradition (Yonkers, NY: St. Vladimir’s Press, 2012), 82-3.