In 1915, Dr. Carter G. Woodson, a pioneering black intellectual and the son of former slaves, recognizing “the dearth of information on the accomplishments of blacks . . . founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, now called the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH).”

Dr. Woodson and the ASALH would later, in 1926, establish the celebration that would go on to become known as Black History Month, choosing the month of February in order to coincide with the birthdays of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln.

Today, the ASALH continues Dr. Woodson’s legacy as the progenitor of Black History Month by “disseminating information about black life, history and culture to the global community.”

Throughout our history, UC Press is proud to have published a great volume of work concerning the topics of black art, literature, politics, and more. Please join us throughout the month as we participate in this global celebration of black history.

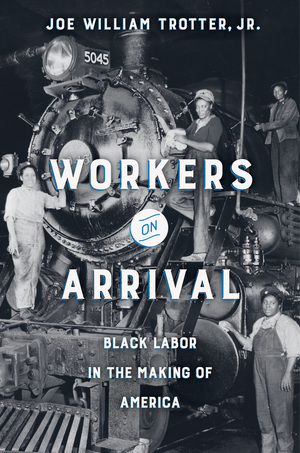

Workers on Arrival

Black Labor in the Making of America

by Joe William Trotter Jr.

“An eloquent and essential correction to contemporary discussions of the American working class.”

—The Nation

In his engrossing new history, Joe William Trotter, Jr. charts the black working class’s vast contributions to the making of America. Covering the last four hundred years since Africans were first brought to Virginia in 1619, Trotter traces black workers’ complicated journey from the transatlantic slave trade through the American Century to the demise of the industrial order in the 21st century. At the center of this compelling, fast-paced narrative are the actual experiences of these African American men and women. A dynamic and vital history of remarkable contributions despite repeated setbacks, Workers on Arrival expands our understanding of America’s economic and industrial growth, its cities, ideas, and institutions, and the real challenges confronting black urban communities today.

The Color Line and the Assembly Line

Managing Race in the Ford Empire

by Elizabeth Esch

“Provides a useful starting point for examining Ford’s adaptation of its labor practices to differing national contexts. Historians and historically minded social scientists will find this book to be an accessible, informative, and engaging contribution to the literature about Ford.”

—Journal of Interdisciplinary History

The Color Line and the Assembly Line tells a new story of the impact of mass production on society. Global corporations based originally in the United States have played a part in making gender and race everywhere. Focusing on Ford Motor Company’s rise to become the largest, richest, and most influential corporation in the world, The Color Line and the Assembly Line takes on the traditional story of Fordism. Contrary to popular thought, the assembly line was perfectly compatible with all manner of racial practice in the United States, Brazil, and South Africa. Each country’s distinct racial hierarchies in the 1920s and 1930s informed Ford’s often divisive labor processes. Confirming racism as an essential component in the creation of global capitalism, Elizabeth Esch also adds an important new lesson showing how local patterns gave capitalism its distinctive features.

Race and the Invisible Hand

How White Networks Exclude Black Men from Blue-Collar Jobs

“As acute in its analysis as it is rich in ethnographic detail, Royster’s captivating study shows in telling detail how inequalities in the securing of good working class jobs are reproduced in the anything-but-colorblind contemporary United States.”

—David Roediger, author of Colored White: Transcending the Racial Past

From the time of Booker T. Washington to today, and William Julius Wilson, the advice dispensed to young black men has invariably been, “Get a trade.” Deirdre Royster has put this folk wisdom to an empirical test—and, in Race and the Invisible Hand, exposes the subtleties and discrepancies of a workplace that favors the white job-seeker over the black. At the heart of this study is the question: Is there something about young black men that makes them less desirable as workers than their white peers? And if not, then why do black men trail white men in earnings and employment rates? Royster seeks an answer in the experiences of 25 black and 25 white men who graduated from the same vocational school and sought jobs in the same blue-collar labor market in the early 1990s.