By Niko Vicario, author of Hemispheric Integration: Materiality, Mobility, and the Making of Latin American Art

Writing a blog entry for the University of California Press website while self-isolating in Brooklyn in late March of 2020, I cannot help but be affected by the global pandemic. As an art historian, I am one of those people inclined to find meaning (sometimes a wild excess of meaning) in things that exist and this practice gives me solace even if it does not make the problems of the world dissipate. It’s in this spirit that I write about my forthcoming book.

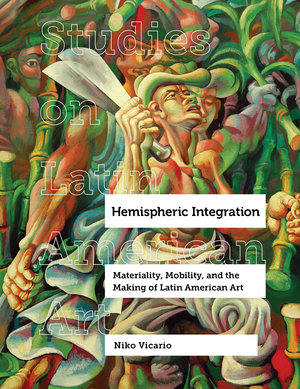

Hemispheric Integration: Materiality, Mobility, and the Making of Latin American Art focuses on the 1930s and the 1940s and art made during that period. I began the project before the election of Donald Trump, an event which shifted a great deal of attention in this country from the global to the national scale: What is this place and how did we get here? Of course, in Trump’s discourse, the United States is defined partially in relationship to its border with Mexico and partially in relationship to Chinese manufacturers’ productivity within global supply chains, among other dynamics, and of course, the global refugee crisis and climate change have kept the planetary scale in view. My book focuses on an era when the U.S. was beginning to throw its weight around on the international stage but a moment also characterized by a shifting and often intimate relationship with Latin America different from the openly antagonistic one promoted, with a few exceptions, by Trump. The book seeks to analyze how a process called “hemispheric integration” came to typify not just political and commercial spheres but also cultural production and the particular ways in which works of art were made and the forms they ended up taking.

True to its subtitle, the book emphasizes materiality and mobility, thinking about a time when global trade was being reconfigured. Material flows registered shifting geopolitical and geo-economic networks within which raw materials like oil and coffee, paints of various kinds, artists, works of art, and ideas were variably mobile. As I write this blog post, questions of materiality are dominated by surfaces, namely how long COVID-19 might last on metal, cardboard, plastic, food, skin. The Internet braces itself for Zoom meetings of various types and an even higher-than-normal reliance on its platforms for social connection—suggesting an apotheosis of the virtual—at the same time that the global pandemic reminds us that screens too are material surfaces that may be contact zones for infection. Questions of mobility are inflected by immobilizations, ranging from quarantine to social distancing. When a book such as mine is ordered online, one is acutely aware—whether or not one had been already—of the conditions affecting the people retrieving it from a warehouse and the people delivering it to the doorstep.

My “solo exercise” since the Stay-at-Home Order has sometimes involved walking to Domino Park, a conversion of a section of the Williamsburg, Brooklyn waterfront into a recreational space. It is named thusly because of the disused Domino Sugar factory building next to it, where artist Kara Walker created a site-specific installation a few years ago, as the area was on the cusp of development. For that work, A Subtlety (2014), Walker oversaw the fabrication of a number of figural sculptures variably out of white sugar and darker molasses. A history of slavery fueling the sugar industry was conjured by these sculptures. So too did artists like David Alfaro Siqueiros, Joaquín Torres-García, Cândido Portinari, and Mario Carreño, among others, engage with the relationship between art and raw materials, as I write about in my book. They produced works of art that reflected on the relationship between art and export commodities, not least when those works of art were mobilized like export commodities in search of a market abroad. Now that the sugar factory has become a ruin, we see industrialization’s rusty aftermath, an industrialization just on the horizon for the artists I write about in Hemispheric Integration.

In the last week I’ve begun reading Susan Stewart’s new book The Ruins Lesson: Meaning and Material in Western Culture. I was initially attracted to purchasing it because of a new project I have begun researching and writing that places a great deal of emphasis on the value of surfaces—some smooth, some rough, some polished, some dirty—for thinking about art and architecture of the past twenty-five or so years, and my walks to Domino Park have helped ground these interests in local examples, the local proving increasingly handy as mobility feels like less and less of an option for those for whom it was a recent privilege. As in Hemispheric Integration, materiality and mobility also have important roles to play in this work-in-progress. The Ruins Lesson has allowed me to think about the current system as a ruin, or as a ruin of a ruin, and to think about what comes next. In some ways the 1930s and 1940s ushered in the world we have been occupying, in other ways it was a stage in a longer process. I hope—following recent work by Anna Tsing and Donna Haraway—that the world we build on these ruins will be a better one.