Koen Leurs is Assistant Professor in Gender and Postcolonial studies at the Graduate Gender Program in the Department of Media and Culture Studies at Utrecht University, where he is a feminist internet researcher investigating the digitalization of migration, diaspora and youth culture. Tomohisa Hirata is a member of the Social and Information Studies faculty at Gunma University, Japan, and an author of The Digital Divide: The Internet and Social Inequality in International Perspective (Routledge, 2013). Together, they are guest editors of the special collection Media, Migration, and Nationalism, which was recently published in the Communication and Media Section of UC Press’s journal Global Perspectives.

UC Press: Welcome, and thank you for your contributions to Global Perspectives!

KL & TH: Thank you for this invitation. We as editors, also on behalf of the 13 contributing authors, would like to express our gratitude and acknowledge Payal Arora, the Global Perspectives “Media and Communication” section editor, who championed our idea for this special issue from the beginning. Alongside Payal Arora, we were expertly and patiently supported throughout the publication and editorial process by Roxi Cui-Olssen and Victoria Balan at Erasmus University Rotterdam, as well as by the University of California Press, Liba Hladik, Erica Olsen, and Jeff Hester in particular.

UC Press: How did this special collection of papers on media, migration and nationalism come about?

KL & TH: This special issue is the culmination of the seminar and master class Media, Migration and the Rise of Nationalism: Comparing European and Asian Experiences and Perspectives, held from September 19–22, 2018 in Tokyo, Japan. From both our situated contexts, as media and migration researchers based at Utrecht University, the Netherlands, Europe, and Gunma University, Japan, East-Asia, we shared a felt urgency to address the resurgence of nationalisms across the world. Particularly we felt pressed to question how renewed nationalisms are co-shaped by (new) forms of mediation and often appear in response to evolving patterns of migration. For this purpose, over the summer of 2017 we applied for Bilateral funding with the Dutch Research Council (NWO) and Japan Society for Promotion of Science (JSPS), to jointly organize a seminar on the topic, and facilitate an exchange by a select group of students and researchers from the Netherlands and Japan working on the themes.

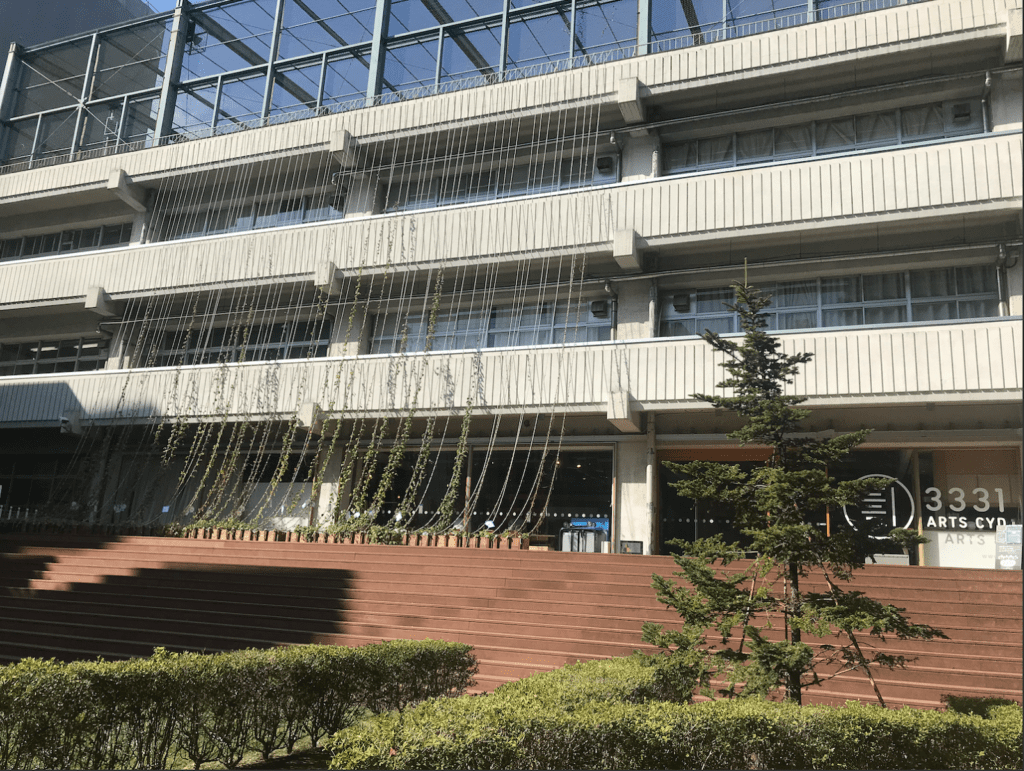

When the application was successful, we decided to organized the public seminar in the community space of 3331 Arts Chiyoda.

The philosophy of this venue is to establish a place to encounter difference through a multiplicity of cultural expressions. Based in the renovated Rensei Junior High School 3331, the community-centred public venue collapses cutting edge art with the familiar everyday. Similarly, our philosophy of the seminar was to ensure inclusive encounters, between disciplines and perspectives. We felt it particularly pertinent to move beyond the dominant Euro-American focus in the study of media and migration studies. Aiming to offer global perspectives, while remaining attentive to the workings of power as an including and excluding mechanism, as well as seeking to establish an interdisciplinary understanding of media, migration and nationalism, a selection of papers presented at the seminar were selected for this issue, alongside a selection of papers presented at the International Communication Association conference held in Washington, DC (USA) in 2018.

UC Press: What are some of the ways that media—whether traditional mass media, or contemporary, decentralized social media—have contributed to the rise in nationalism we’ve seen globally in recent years?

KL & TH: In the return on the stage of nationalisms in recent years, migrants have been discursively constructed as scapegoats. Specific mobile populations, particularly migrant workers and refugees have been minoritized and racialized as threats or burdens to nation-states in dire attempts to grasp, make tangible, or deny failures and/or limitations of systematic planetary conditions. As Arjun Appadurai has acutely observed, “migrants, especially refugees, in the contemporary globalized world are inevitably second-class citizens because their stories do not fit the narrative requirements of modern nation-states” (2019, 558). Simultaneously, supported by media formations including targeted social media campaigning, we see nationalist rhetoric take centre stage for example, in the election of populist, protectionist, racist, and sexist presidents in the United States, Brazil, and Russia as well as in the UK Brexit vote.

The co-shaping of nationalism, mediation and migration is particularly striking in several recent manifestations of ‘global crises’: most notably the economic crisis, climate crisis, refugee crisis, the COVID-19 crisis and most recently the global #BlackLivesMatter human rights movement.

In their mediation, crises politicize difference. A global perspective on media, migration, and nationalism demands that we become critical of what these crises are and are not doing (on the discursive and material level) across geopolitical and situated manifestations. Notwithstanding the unchanged interconnectedness of global capitalism, media, technologies, and networks, these global crises have variously resulted in populist deglobalization stances, action, and rhetoric, resulting in nationalism, parochialism, and isolationism.

UC Press: Tell us about the papers that comprise Media, Migration and Nationalism.

KL & TH: Besides our introductory essay, the special issue consists of 13 articles, which we have categorised in 4 sections: (1) cosmopolitanism and polarization; (2) migration management and border control; (3) diaspora, transnationalism, and networks; and (4) cities and social media as contact zones. In our aim to build bridges beyond academia four artists joined our seminar: Takashi Tanihata, XX, Motoi Hirata, and Satsuki Hinokimoto. These artists provided their visual impressions of the seminar themes. Below, we include the works of the four artists and in our introductory essay we provide further details and figurative and poetic reflections by the artists.

“the artworks depict an endless loop of (mis)communicating goats, which represent the possibilities and implications of mediated solidarity and polarization”

Section 1 of the article focuses on cosmopolitanism. This thorny scholarly debate is captured by the artist Takashi Tanihata in the works A Letter That Isn’t Read I and II. Tanihata turned to the famous Japanese nursery rhyme “Goat Mail” for inspiration. In the rhyme, a black goat receives a letter from the white goat. Upon arrival, she eats up the correspondence before reading. In return the letter sent by the white goat is eaten up by the black goat before reading.

As we discuss, the artworks depict an endless loop of (mis)communicating goats, which represent the possibilities and implications of mediated solidarity and polarization. The special issue features three articles—authored by Sandra Ponzanesi, Tuija Parikka, and Jülide Etem—that further nuance the heated debates on the politics of representation and mediation in relation to cosmopolitanism.

Section 2 of this article is thematized with a painting by the artist XX (a pseudonym), titled The Scents on the Borders, which depicts perfume bottles and their scents encountering each other. The work, as we argue, refers to the complex, evolving relationships between border-crossing subjects and technologies of migration management and control. A latest development shows how tech-driven surveillance experiments tap into sensing technologies including those related to the sense of smell to detect mobilities and secure borders. The section consists of four articles written by Huub Dijstelbloem, Christine Quinan & Nina Bresser, Sanne Boersma and Gerwin van Schie, Alex Smit & Nicolás López Coombs. The articles demonstrate how the politics of material and symbolic bordering proliferates outside and inside nation-state boundaries.

Section 3 takes inspiration from an artwork titled The Vision (Reportage), by Motoi Hirata, which features violet sea snails that can drift on the surface by producing bubbles. The snails however do not cross paths, but their bubbles may. This motif represents migrants and diaspora groups who face situations of physical separation from loved ones, friends, and wider communities, but seek to stay in touch through forms of digital networks. The section includes three articles, by Jesse van Amelsvoort, Elisabetta Costa & Donya Alinejad and Jeffrey Patterson & Koen Leurs. The articles analyze processes and lived experiences of connectivity, emotions, transnationalism and home-making across nation-state borders.

In section 4 of this article, we take cues from Satsuki Hinokimoto’s abstract painting The Spread and link its deployment of isolated and interacting colored concentric circles to the evocative scholarly concept of the cultural contact zone. This section of the issue consists of three articles by Pramod Nayar, Fiona Seiger & Atsumasa Nagata and Camila Sarria Sanz & Amanda Alencar that focus on migrant encounters with difference and the politics of integration in various urban settings across the world.

UC Press: What would you like readers to take away from this collection of articles?

KL & TH: Media, migration, and nationalism emerge at specific junctures, resulting from specifically situated geopolitical, cultural, economic, political, emotional, and environmental processes. In contributing to a global turn in media studies, this special issue has offered context-specific conceptual and empirical reflection on mediated, digitized, and datafied processes co-shaping migration and nationalism across Asia, the Americas, and Europe. Thematically, addressing a variety of mobile subjects including forced migrants, refugees, non-binary-gender- and transgender-identifying travelers, expatriates, the internally displaced, and labor migrants, the articles have reflected on the politics of polarization, bordering, connectivity, and intercultural contact.

Perhaps a sign of its expiry date, or of its full-blown return on the stage—who knows, future will tell—in contemporary forms of mediated nationalism, migrants appear dominantly as the faces representing the faceless enemies of capitalism, global warming, war, health and security risks. Besides nationality and migration status, these forms of mediation often reinstate inequalities along intersecting lines of race, class, gender, sexuality, religion, and embodiment. These dynamics show that “nationalism provides often for an easy and dangerous resource” (Bieber 2018, 537). However, we should not be blinded by assuming that nationalisms are exceptional trends, with rising forms of nationalism tied to isolated geopolitical moments; rather, nationalism is and remains “endemic to the global social system” (ibid).

As the editors, we hope that the readers will gain a deeper understanding of these global dynamics by engaging in a cross-sectional reading of the articles included in the issue. In addition we hope the readers and viewers will find inspiration in the presented collaboration between academia and art. This collaboration, for us, was not just an academic outreach effort, as the art pieces were taken seriously as a form of knowledge production allowing for an exploration of alternative global imaginaries. We would like to cordially thank those who have supported us in publishing in this spirit the special issue of Global Perspectives.

About Global Perspectives’ Communication and Media Section

The “global turn” in communications, advances in mobile technologies and the rise of digital social networks are changing the world’s media landscapes, creating complex disjunctures between economy, culture, and society at local, national, and transnational levels. The role of traditional mass media—print, radio and television—is changing as well.

In many cases, traditional journalism is declining, while that of user-generated content by bloggers, podcasters, and digital activists is gaining currency worldwide, as is the impact of robotics and artificial intelligence on communication systems.

Today, researchers find themselves at important junctures in their inquiries that require innovations in concepts, frameworks, methodologies and empirics. Global Perspectives aims to be a forum for scholars from across multiple disciplines and fields, and the Communication and Media Section invites submissions on cutting-edge research on changing media and communication systems globally.

About Global Perspectives

Global Perspectives is an online-only, peer-reviewed, transdisciplinary journal seeking to advance social science research and debates in a globalizing world, specifically in terms of concepts, theories, methodologies, and evidence bases. Work published in the journal is enriched by invited perspectives that enhance its global and interdisciplinary implications.

Editor-in-Chief: Helmut K. Anheier, Hertie School and Luskin School of Public Affairs, UCLA