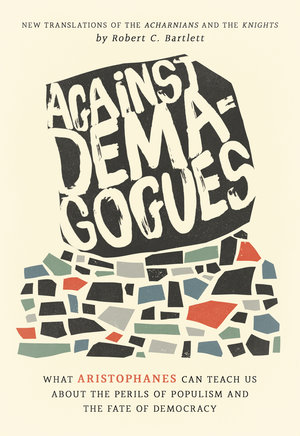

by Robert C. Bartlett, author of Against Demagogues: What Aristophanes Can Teach Us about the Perils of Populism and the Fate of Democracy, New Translations of the Acharnians and the Knights

It’s fair to say that ours are troubled times, with deep economic division, racial strife, and even a plague still dogging us. Add to these a bruising election for president in which nobody agrees on anything except that the stakes are sky-high. We could use a little relief, you and I. But where to find it? Consider, I suggest, Aristophanes, the supreme jokester of antiquity. His eleven surviving comedies are bawdy, slapstick, and wildly inventive, and they retain a remarkable freshness. What’s more, one of his earliest plays, the Knights (424 BCE), supplies a tonic we could use right about now.

The Knights isn’t much performed today, but it should be. It reads as though written by the love child of Tom Stoppard, Dr. Zeuss, and Marx (more Groucho than Karl). Aristophanes’ main opponent in it is the democratic politician Cleon (died 422 BCE), the loudest advocate of war in Athens. Thucydides calls him “the most violent of the citizens” and “by far the most persuasive with the people at that time.” Aristophanes calls him a “demagogue.” But what exactly is that?

The earliest instance we have of the Greek term for demagoguery (demagogia) appears in the Knights. It meant initially no more than “leading the demos,”the demos being the largest political class that is by definition the poorest and so the least educated. But “demagoguery” soon came to have the same odor it has for us. A demagogue is an unscrupulous master of slippery rhetoric who, for his own ends, plays the crowd like a cheap fiddle. As a character in the Knights puts it, “demagoguery no longer belongs to a man acquainted with the things of the Muses or to one whose ways are upright / But to somebody unlearned and loathsome.”

In the play Cleon is dubbed “Paphlagon” (roughly “Blusterer”), a servant of the Athenian people who are presented as a single householder, Mr. Demos. (Think Uncle Sam.) Athens’s two greatest generals at the time, Demosthenes and Nicias, also appear as servants of Mr. Demos and so see first-hand the dirty tricks Paphlagon-Cleon is up to. In cooperation with the upper-class knights, these great military men plot to restore Athens to something like the grandeur of its past. Make Athens Great Again!

They decide there’s only one way to rid the democracy of Cleon. They enlist for the purpose a completely unknown member of the demos, a lowly sausage-seller who is uneducated and amazingly, hilariously, crude. In other words, just the man to out-Cleon Cleon! Some, by the way, have compared this strategy to the attempt of the upper-class Prussian Junkers to enlist one Adolph Hitler as a useful tool to rid Germany of the Weimar Republic. There’s something to the parallel, though it unfortunately likens the affable Sausage-seller to the head of the Nazi party. In any case, Demosthenes and the knights are only partly successful. The Sausage-seller does manage to replace Cleon in the affections of Mr. Demos. But he proves so able a democratic leader that he is not the mere puppet the upper-classes are hoping for.

What then is the message of the Knights? Athens must flush Cleon out of its political system. He is an unsavory and unhealthy type, bad in himself and for the democracy. He despises the very people he nonetheless feels compelled to fawn over. He says whatever he thinks Mr. Demos wants to hear. He promises endless material goods and bodily comforts, something well known to us: inexpensive universal healthcare, “free” tuition, a bump in the old age pension, all of it with a lower tax bill. Or no bill at all!

So the successful demagogue has to curry favor with the masses constantly, even as he enriches himself through bribes and shakedown operations. He’ll also attack all who, by seeking high office themselves, dare challenge his power. Here the tools of the trade include slander, the threat of lawsuits, and trumped up charges to damage a reputation: rumor, innuendo, conspiracy. Cleon is in short a master of calumny. He’s so brazen that he’ll rob others of their good name while taking credit for their good deeds.

“Do we today bear no responsibility for the leadership that is ours? Are our leaders not duly elected, and re-elected, by us? Appeals to our worst instincts tend to work for the simple reason that those instincts really are ours. Must we surrender to them?”

But—and here we come to some tough advice from the poet—Aristophanes shows that a demagogue could never succeed without one crucial thing: a demos, a people, eager to be led. Even off a cliff. Do we today bear no responsibility for the leadership that is ours? Are our leaders not duly elected, and re-elected, by us? Appeals to our worst instincts tend to work for the simple reason that those instincts really are ours. Must we surrender to them? Aristophanes is not without hope on that score. Accordingly, he doesn’t spare the Athenian people, who make up the bulk of his audience and laugh at the jokes that sometimes also sting. He charges them with being gullible, “half-deaf,” too quick to anger, suckers for flattery, and ignorant of what’s being done at home and abroad in their name. If Cleon always flatters, Aristophanes sometimes punches. Where is our Aristophanes who can call us to account—not this or that party, Left or Right, progressive or conservative, but the American people? No serious candidate for national office will ever do it. O Comedy, where is thy sting? We could use it.

As Aristophanes knew, the human soul can’t experience anger and laughter simultaneously. The one crowds out the other. In these parlous times, when causes of moral indignation abound, we need the therapeutic that is laughter: less anger. And more than just a pleasing diversion, the laughter prompted by great comedy can also help make the medicine go down. So in my capacity as a doctor (of philosophy) I prescribe a dose of Aristophanes for what ails us. Take as needed. More than any other comedian I know of, Aristophanes happily plays the fool in order to encourage his audience to be nobody’s fool. We could do worse, you and I.