This blog is adapted from an original article published in CENTRO, with permission, and is part of our AAA #RaisingOurVoices2020 event blog series. Check out our virtual exhibit page for more.

By Ismael García-Colón, author of Colonial Migrants at the Heart of Empire

Colonial Migrants at the Heart of Empire explores how the Puerto Rican experience in farm labor challenges our understanding of U.S. citizenship and its relation to immigration policies. In 2015, the U.S. Department of Labor announced charges against a farm in New Jersey for unlawfully rejecting Puerto Ricans who applied for employment. The farm showed preferential treatment to guestworkers and provided working conditions less favorable to Puerto Ricans in violation of the H-2A visa’s regulations. Immigration law requires farms hiring workers to recruit domestic workers first and offer them the same wages and working conditions as to H-2A workers. Employers’ ability to deport guestworkers has rendered Puerto Ricans and other U.S. citizens less desirable for agricultural work.

Nowadays, Puerto Rican farmworkers are imperfect migrants for the majority of employers. Guestworkers and undocumented workers have become “perfect immigrants” for an agrarian labor regime characterized by a low-wage, deportable, and seasonal labor force. Being less desirable for agriculture does not imply that Puerto Rican workers are in a worse position than guestworkers or that being a guestworker is a privileged position. Rather, my book Colonial Migrants at the Heart of Empire emphasizes the long history of ironies and contradictions in the ways that farmers and government officials acted in regard to farm labor.

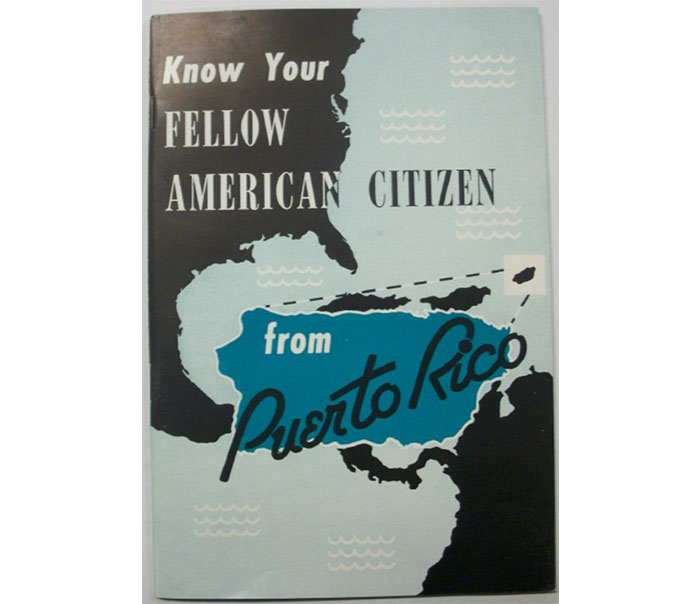

The use of Puerto Ricans in U.S. agriculture depended greatly on their membership status within the U.S. nation. After the Spanish-American War, Congress allowed the incorporation of Puerto Ricans into the U.S. labor market by defining them as U.S. nationals with limited rights. Between 1899 and 1917, Puerto Ricans migrated to U.S. territories such Hawaii and Cuba. Employers used them to replace labor migrants that the Chinese Exclusion Act and the Foran Act prohibited. The granting of U.S. citizenship in 1917 facilitated the recruitment of Puerto Ricans, but also began to mark their undesirability.

In 1947, the government of Puerto Rico enacted Public Law 89 requiring contracts and government approval when hiring workers in its jurisdiction. Using the experiences of the Bracero Program, the government designed a farm labor program for recruiting migrant workers. The government also approved Public Law 25, creating the Bureau of Employment and Migration with its Migration Division, and in charge of the Farm Labor Program. The U.S. colonial status allowed the insertion of Puerto Rico’s officials in the structures of the U.S. Department of Labor, the creation of the Migration Division as an agency operating stateside, and lobbying on behalf of Puerto Rico by congressional representatives and officials of the U.S. Office of Territories. However, it was only in the 1950s that Puerto Ricans became fully recognized as domestic workers for purposes of labor market regulations contained in the Wagner-Peyser Act.

Despite these efforts, officials continuously confronted the fact that employers opposed Puerto Ricans because they were citizens and immigration authorities could not send them back. U.S. colonialism and citizenship created in practice an ambiguous status for Puerto Ricans. Discrimination against Puerto Ricans because of their “foreignness” and race continued to occur even though Congress passed the Nationality Act of 1940 and an amendment to it in 1948 clarifying the “native-born” citizenship status of people born in Puerto Rico.

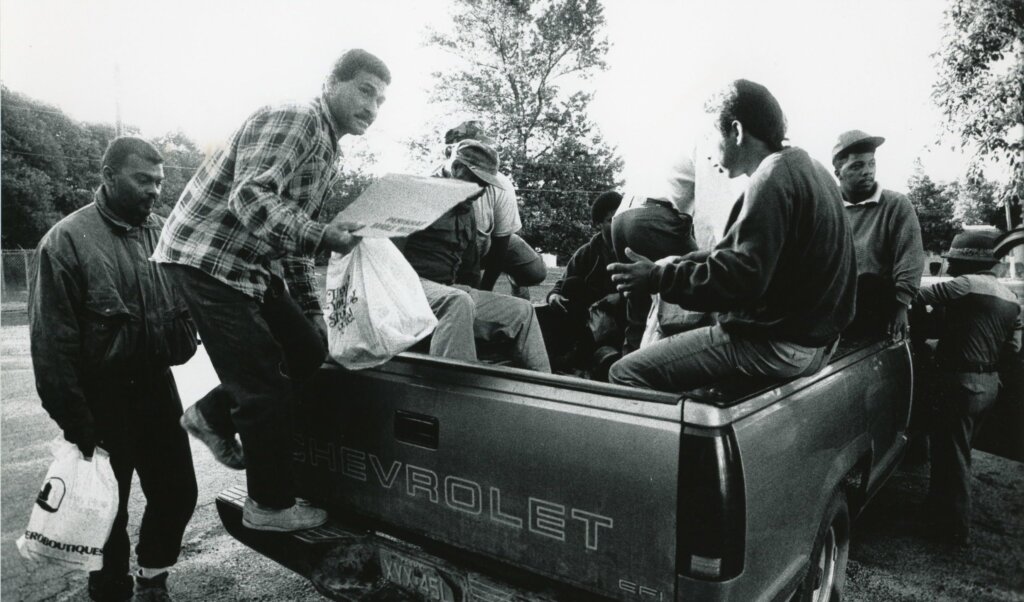

The Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1952 (INA) officially classified workers from Puerto Rico as domestic, giving them preference over guestworkers. The end of the Bracero Program in 1964 and restrictions on H-2 workers increased the hiring of Puerto Ricans. The Farm Labor Program rose to more than 20,000 workers in 1969.

During the mid-1970s, apple growers went to court challenging the preference for Puerto Rican workers over H-2 workers, and were successful. The fact that growers would not have to prefer Puerto Ricans over H-2 workers meant that the courts dismantled the most important pillar of the program. In 1993, the Roselló González administration ended the Farm Labor Program. Still, despite discrimination and shrinking numbers, contemporary Puerto Ricans continue their quest for earning a living by working in U.S. agriculture.

The history of Puerto Rican farmworkers shows that U.S. agriculture has developed a labor regime in which Puerto Rican farm labor is imperfect for employers because U.S. citizenship provides them with rights. Puerto Ricans, as distinctive U.S. citizens and colonial subjects, show the particular place that colonial populations occupy between minorities and immigrants within modern agrarian labor regimes and immigration policies.