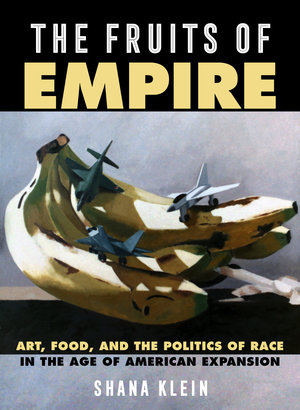

By Shana Klein, author of The Fruits of Empire: Art, Food, and the Politics of Race in the Age of American Expansion

Still-life paintings of food look innocent at first sight. Pictures of bowls bulging with oranges and grapes were fashionable in nineteenth-century American dining rooms, prompting viewers to reach out and touch the painted foods because they looked so tempting and real. Outside the home at world’s fairs, viewers were so attracted to displays of pineapples and bananas that they stole the fruits right off their trees!

But were fruits merely delicious gems and pretty pictures to admire? My book, The Fruits of Empire, argues otherwise.

Divided into five chapters that each focus on a specific fruit, The Fruits of Empire examines the dark, political symbolism behind visual images of grapes, oranges, watermelons, bananas, and pineapples in the decades after the Civil War. Often, these images reflected and shaped conversations about race and national expansion in the United States. Pictures of grapes, for instance, endorsed a new center for American grape culture—California—yet, they also denigrated the role of Mexican and Chinese laborers who harvested the very grapes that catapulted California to success. Pictures of oranges similarly celebrated new fruit industries in Florida, while also encouraging northerners to seize southern land and hire newly freed African-American farmers in the paternalistic mission to teach them to be good citizens. And images of watermelons offered obvious examples of how fruit pictures shaped debates about race. Depictions of African-American men stealing and salivating over watermelons propagated vicious stereotypes about Black people in attempts to diminish their new status as citizens.

Depictions of fruit were not just an accessory to the dining room. They were an accessory to the American empire and a device to endorse America’s growing territorial and economic gains.

Across paintings, photographs, advertisements, and silverware objects, The Fruits of Empire asks: what is depicted or edited out from visual representations of food? Who do images of food serve? And at whose expense? The results are not so delicious.

“Depictions of fruit were not just an accessory to the dining room. They were an accessory to the American empire and a device to endorse America’s growing territorial and economic gains.”

– Shana Klein

Not everything I found was gloom and doom. Each chapter includes powerful examples of artists and image makers who used food imagery to fight against racism and resist imbalances of power. This book also deals with glaring gaps in scholarship by recovering the histories of art and food in overlooked regions such as California, Florida, Hawaii, and Guatemala, in particular highlighting the ways that women used art and food to shape the American empire.

Moving between the fields of art history, visual and material culture, food studies and more, The Fruits of Empire uses a cocktail of methodologies to think more deeply about the visual lives of our food, and how a fruit as small as a grape or as colorful as a watermelon contributed to the nation’s most heated debates over race, labor, and citizenship.

Note: All royalties for this book will be donated to the Coalition of Immokalee Workers, an organization committed to fighting for farmworkers civil rights.