Happy University Press Week 2020! This year, the Association of University Presses‘s theme, “Raise UP” / #RaiseUP highlights the role that the university press community plays in elevating authors, subjects, and whole disciplines, bringing new perspectives, ideas, and voices to readers around the globe. For UP Week’s annual blog tour, today’s specific theme, “Local Voices,” addresses how university press publishing raises up and supports scholarship that focuses on research relevant to very specific histories, geographies, and experiences. Please check out posts by these fellow university presses today as well: Temple University Press, Fordham University Press, Syracuse University Press, Manchester University Press, University Press of Kansas, Penn State University Press, University of Nebraska Press, American School of Classical Studies at Athens, University Press of Mississippi, University of Toronto Press, University of Toronto Press Journals, and University of Virginia Press.

UC Press’s A People’s Guide is a series of guidebooks that uncover the rich and vibrant stories of political struggle, oppression, and resistance in the everyday landscapes of major cities. Much as Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States infiltrated the standard history textbook with untold stories of the nation’s past, the series reveals an alternative view through the format of a guidebook. These books tell histories from the “bottom up,” and also show how landscapes are the product of struggle. Each book includes sites where the powerful have dominated and exploited other people and resources, as well as places where ordinary people have fought back in order to create a more just world.

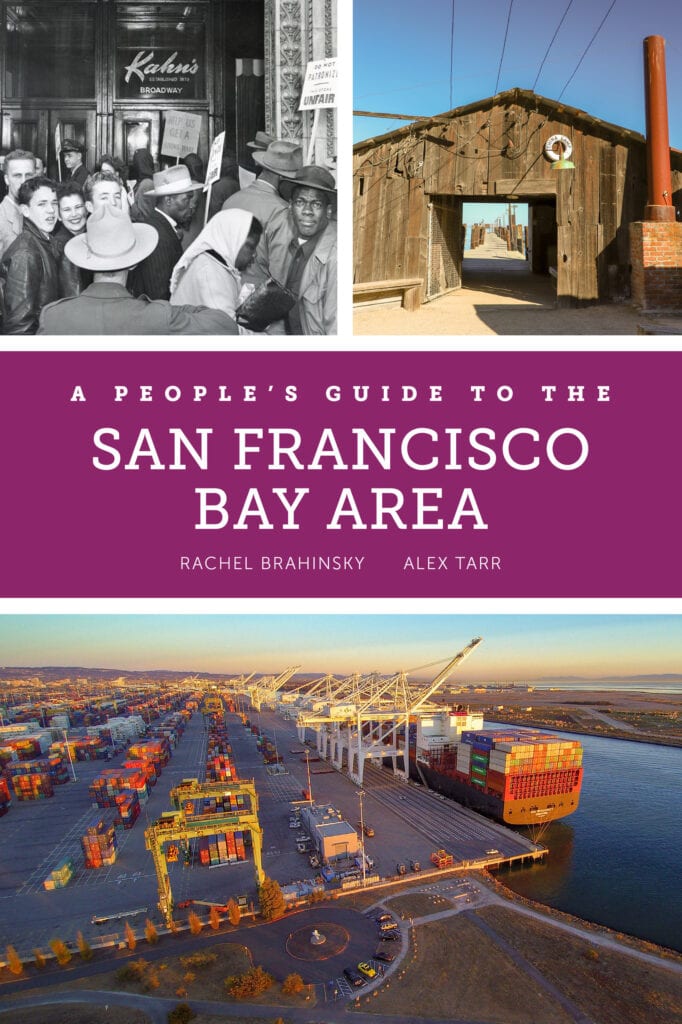

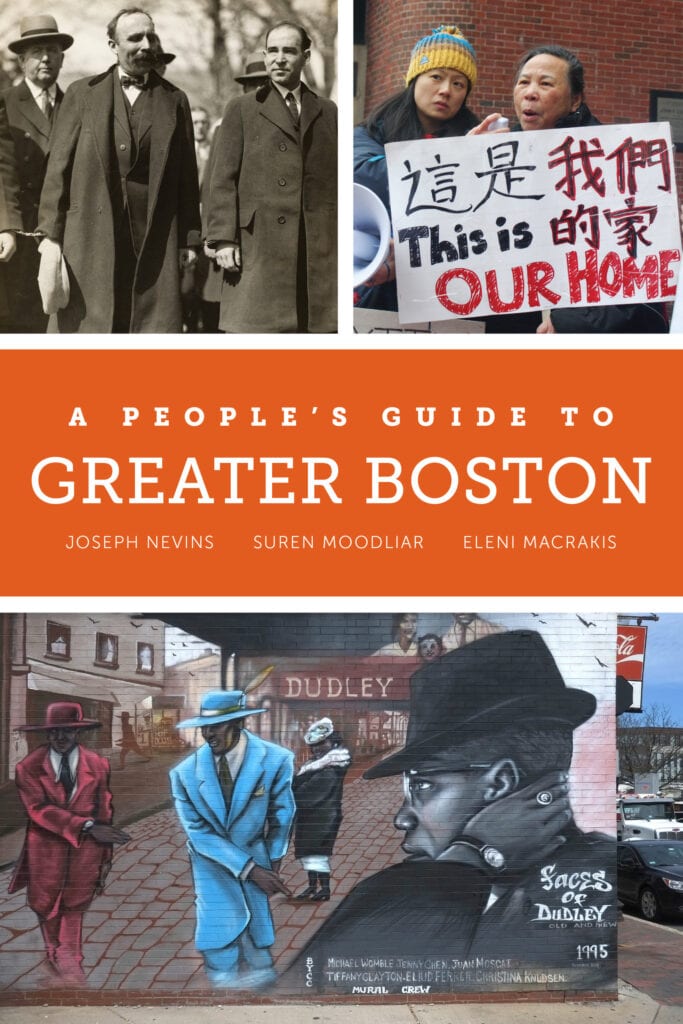

Two new additions to the series have recently been published, A People’s Guide to Greater Boston by Joseph Nevins, Suren Moodliar, and Eleni Macrakis, and A People’s Guide to the San Francisco Bay Area by Rachel Brahinsky and Alexander Tarr. Please enjoy the following guest contribution by the San Francisco guide’s coauthor, Rachel Brahinsky, along with an excerpted entry from the Boston guide.

The voices behind the places. Or: How listening to everyday people helped us paint a picture of a Bay Area that you’ve never seen before…

At the heart of A People’s Guide to the San Francisco Bay Area are 100 essays about places that draw on formal and informal archives, stories handed down for decades, and the landscape itself. One of my favorite elements, though, is a set of personal reflections from locals that frame those essays, offering primary-source, living examples of the themes and stories that thread through the book. These are sections where we feature the voices of people who produced the Bay Area through their activism, their intellectual work, their creativity, and their care. Fundamentally, the “community voices” offer a chance to hear directly from the people that made those places.

We open the book with a quote from NTanya Lee, a longtime political organizer with particularly deep roots in Black and Latinx working-class communities. She talks about the mystique of the Bay Area, and how she was drawn to live there in part because of its inspiring activist legacies. Over time, though, she began to understand the deeper histories and struggles behind the region’s “progressive” reputation, and she helps us highlight one of the core purposes of our book with this quote:

“When people think about the ‘Bay Area bubble,’ they’re often thinking more of the hippies of Berkeley than the communists in Chinatown, the Marxists in Oakland who started the Black Panther Party, or the feminists of color that created all kinds of local institutions in the 1980s. Understanding these stories give us a window into what kinds of leadership and struggle are required for the transformation of the whole country. It shows us what makes the Bay Area both special and not so different from elsewhere.” (p. 7)

Later we tell the story of 924 Gilman, a subcultural event venue in Berkeley with a fierce dedication to independent music and providing a safe all-ages space through prohibitions of racism, misogyny, homophobia, drugs, and alcohol at its shows. Artist and singer Ivy Jeanne talked to us about the ways that the place built a special community for people who felt – even in the Bay Area – like outliers or outcasts. She also touched on the cultural landscape of the neighborhood, a longtime industrial section of Berkeley, which has been a central part of Gilman’s identity and appeal, especially to people living on the edge of the economy. Here’s part of her story:

“In the summer of ’93, I squatted across the street from Gilman with my old punk band Los Canadians in a massive abandoned warehouse that was formerly a lift-and-pulley machining shop. It really speaks to the area, which was a desolate and forgotten industrial zone. I think that’s why Gilman was able to really plant roots and stay open… I would find the runaways, the weirdos, the travelers, and invite them to stay across the street, saying ‘Hey, you’ve got a place.'” (p. 25)

In our chapter on the North Bay, we focus quite a bit on sites of ecological challenges, and they always have a socio-cultural angle as well, which comes through in our interviews with locals on the ground. One of these is the China Camp State Park, a wonderful place to hike and explore, which contains important history that is too-often overlooked. Rene Yung, the director of a community storytelling project called Chinese Whispers, talked to us about her work to preserve and uncover stories of the international shrimp-export operation that made this place a key economic and social center for Chinese immigrants and their descendants. As she put it:

“You hear about the railroad, you hear about the mines, you hear about laundry and restaurants, but somehow Chinese maritime history has been a hidden story, and there is a strong relationship between the loss of this history and the loss of the landscapes where these events happened.” (p. 202)

All told, these voices and others bring light and life to the narratives that we weave throughout the book. They help show readers not just where places are, but whose struggles and dreams create those places. By shedding light on the lives of everyday people the book is also a useful tool for local people to build from—and for people elsewhere to learn from—as they engage in their own work to make their hometowns better and more socially-just places.

Combahee River Collective

26a Moultrie Street

DORCHESTER

In 1974 a group of black women activists, each with long histories in the antiwar, feminist, and black liberation movements, began to gather in one another’s homes in Boston’s working-class communities. The first place was Demita Frazier’s living room on Moultrie Street, where regular meetings occurred in the early years. In this intimate space, they analyzed their diverse commitments to these movements while lamenting the estrangement they experienced in male-led and/or white-dominated formations. In their conversations, Frazier, the twin sisters Barbara and Beverly Smith, and several others addressed the challenges facing working-class, black women activists, noting the energy and emotional work they invested in various coalitions given the interlocking character of their oppression. Considering matters of gender, class, race, and sexual

orientation, they evolved a theory of liberation that has proved to be very influential in academia and among social justice organizers, one based on the insights provided by multiple intersecting oppressions and the resulting coalitions: with black men in the fight against racism, with white women in the struggle against male domination. Acknowledging also their class position, they defined themselves as socialists aiming to overthrow capitalist social relations. In this sense especially, they reflected a very different political orientation from the National Black Feminist Organization in which several of them had participated.

Naming themselves after an 1863 military campaign led by Harriet Tubman that freed 750 enslaved individuals in South Carolina, the collective foregrounded their commitment to action. This was not an abstract choice: The collective was founded in the midst of a Boston “race war” triggered by white opposition to integrated schools. Members of the collective themselves, especially the Smith sisters, had a background in organizing “freedom schools” during the Civil Rights movement.

Although the collective was itself a breakaway from mainstream feminism, its coalitions reached out broadly to address concrete issues of reproductive freedom, forced sterilization, and violence against women. They also called attention to a series of murders and violent attacks against black women that were going uninvestigated by the Boston Police Department. Their community-based research and reports engaged both The Boston Globe and local African American papers, which had been underreporting these incidents. By the late 1970s, their public demonstrations addressing these attacks had drawn broad public support and produced a strong coalition of feminist and community-based activists. The coalition’s organizing work prefigured future Boston coalitions, including most directly the Rainbow Coalition mayoral candidacy of Mel King in 1983.

During their later years, the collective met regularly at the Women’s Center in Cambridge. The coalition disbanded in 1981 as its members moved on to other activities, including academic work.

GETTING THERE

Red Line to Shawmut Station. The private residence is a 0.3 mile (three-minute) walk.