By Catherine S. Ramírez, author of Assimilation: An Alternative History

This post was originally published on University of Southern California Equity Research Institute blog and is reposted here with permission.

During their first presidential debate, Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton accused Donald Trump of not paying federal income taxes. Her Republican opponent, she averred, paid “zero for troops…vets…schools or health.” Rather than deny this charge, Trump boasted, “That makes me smart.” Four years later, on September 27, 2020, the New York Times reported that he paid no income taxes for ten years and only $750 in federal income taxes in 2016 and $750 in 2017.

While Trump has bragged about not paying taxes, immigrants and their advocates have stressed immigrants’ contributions to the United States. We’re reminded that immigrants pay billions of dollars in taxes annually and fill jobs that most US citizens don’t want. The current public health debacle has underscored that immigrant workers are disproportionately represented in “critical infrastructure” industries, such as health care and agriculture.

In my home state of California, farmworkers, many, if not most, of whom are undocumented, continue to harvest crops, despite the ongoing pandemic and the hottest summer and largest wildfire season on record. Every pyramid of apples and oranges I encounter at the market is more than a testament to their labor; it’s also a reassuring sign of normalcy during a moment of overlapping crises.

On March 27, 2020, the $2 trillion Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act was signed into law. The largest relief package in US history, the CARES Act distributed $1200 cash grants to tens of millions of Americans. For the first time ever, it expanded jobless aid to independent contractors. However, the CARES Act excluded many immigrants, particularly the undocumented and their US-citizen and legal permanent resident relatives, even if they were essential workers. In the United States, it’s possible to be essential and excluded at the same time.

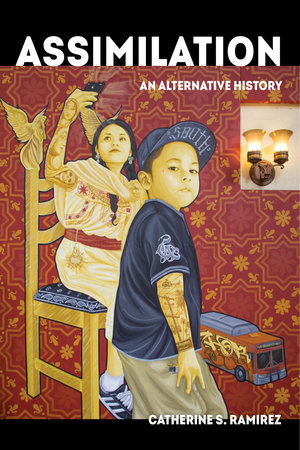

My book, Assimilation: An Alternative History, reckons with this paradox. Rather than approach assimilation as a process of blending in or becoming more alike, I show that it’s a relational process whereby the boundary between unequal groups and between inside and outside blurs, disappears, or, paradoxically, is reinforced. I study how social groups that aren’t immigrants in the United States, such as Indigenous Americans, Puerto Ricans, US-born Japanese Americans, and enslaved Africans and their US-born descendants, and groups that aren’t recognized as real or legitimate immigrants—namely, the undocumented—have been assimilated as racialized and subordinate subjects.

One way I bring assimilation’s history as a process of differential inclusion into relief is by looking at probationary citizenship. Probationary citizens are people whom the dominant society considers outsiders and who must show that they merit acceptance by fulfilling a series of conditions. To prove their worthiness for inclusion, probationary citizens need to demonstrate that they’ve adopted the dominant culture’s mores and customs.

Put another way, they must acculturate. What’s more, they’re expected to contribute to society, especially to the market. Above all, probationary citizens must demonstrate that they aren’t and won’t become a burden to society. In the United States, jumping through these sorts of hoops has been part of the assimilation process for people of color, natives and newcomers alike.

For example, if Native Americans wanted to be US citizens prior to 1924, they had to live “separate and apart from any tribe of Indians,” take up “the habits of civilized life,” and show that they were “competent and capable of managing [their] affairs” over a period of 25 years. It’s not clear how many earned US citizenship after their 25-year trial. However, by the time Congress passed the Indian Citizenship Act in 1924, 125,000 Native Americans (out of an estimated total population of 300,000) still weren’t US citizens.

Today’s probationary citizens include participants in Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). Established by executive order in 2012, DACA is a program that grants certain undocumented immigrants a temporary stay of deportation and temporary permission to work. DACA doesn’t lead to citizenship or legal permanent residence. In addition to meeting “several guidelines,” DACA participants must renew their status every year for a fee of $495. Temporary, expensive, revocable, and under constant fire by the Trump administration, DACA formalizes its participants’ marginalization and crystallizes the paradox of assimilation.

Supporters of DACA and its abortive predecessor, the Development, Relief and Education for Alien Minors (DREAM) Act, have emphasized young, undocumented immigrants’ deservingness for inclusion in the United States. This has been a well-meaning, albeit unsuccessful strategy for reforming immigration policy. Arguments for incorporating the undocumented that hinge on deservingness haven’t passed the DREAM Act. Instead, they’ve further distinguished the putatively deserving from those deemed less deserving or undeserving.

Recent and proposed reforms to US immigration policy show that the Trump administration also deploys the logic of deservingness. For example, the wealth test, which went into effect on February 24, 2020, requires prospective legal permanent residents to demonstrate that they’re “self-sufficient, i.e., do not depend on public resources to meet their needs, but rather rely on their own capabilities, as well as the resources of family members, sponsors, and private organizations.” Training its sights on those sponsors, the Affidavit of Support on Behalf of Immigrants seeks to harden “the enforcement mechanism…so that sponsors and household members who agree to use their income and assets to support the sponsored immigrant are held accountable if the sponsored immigrant ultimately receives means-tested public benefits.” The Affidavit was proposed on October 2, 2020. US Citizenship and Immigration Services claims it will “more effectively protect American taxpayers.”

Imagine, for a moment, if an immigrant publicly boasted about not paying taxes. While Trump’s hypocrisy enrages me, the wealth test and Affidavit point to the danger of basing immigration policy on the notion of deservingness. President-elect Joe Biden has vowed to reverse the wealth test. His new administration offers the opportunity to build an immigration system that’s both humane and practical.

Rather than ask, Who contributes to society, we can begin by asking, Who’s expected to contribute? Whose contribution is deemed valuable or legitimate? And whose contribution is essential?