By Amanda Lucia, author of White Utopias: The Religious Exoticism of Transformational Festivals

All-white powwows, reggae festivals, and blues festivals are relatively unthinkable in the US context. In contrast, yogic and transformational festivals draw predominantly white spiritual seekers into breathtakingly gorgeous natural environments to engage deeply with expressions of non-white cultural and religious forms.

Why is this?

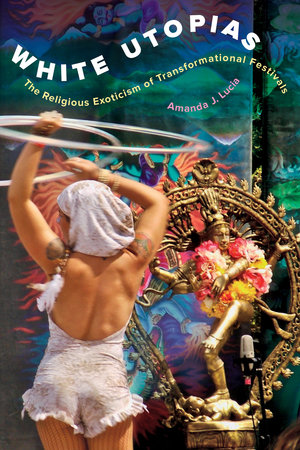

My new book, White Utopias: The Religious Exoticism of Transformational Festivals, looks closely at transformational festivals, analyzing the practices and discourses of the “spiritual but not religious” (SBNR) attendees, and the varieties of religious forms with which they engage. The book is based on nine years of ethnographic research in three different genres of festivals: festivals dedicated to Hindu devotion and yoga—as in Bhakti and Shakti Fest, festivals focused solely on the practice of yoga—as in Wanderlust festivals, and festivals framed around eclectic aspirations of consciousness expansion and spiritual transformation that include yoga—as in Lightning in a Bottle and Burning Man. My research reveals how whiteness is perpetuated in these environments and highlights how SBNR populations build their spiritualities on a foundation of religious exoticism, which otherizes and alienates people of color.

The variety of spiritual practices at these festivals is extraordinarily vast, with practitioners engaging in sound bath healing, Tibetan Buddhist singing bowl meditations, nature religion, crystal skull communication, chakra alignments, crystal healing, ayahuasca medicine, sexuality workshops and multiple therapeutic resources. White Utopias focuses specifically on the practice of yoga—one of the most common offerings in each of these festivals.

In the course of my research, I learned that transformational festivals were functioning as educational spaces for disseminating SBNR ideas and values. And festival yoga classes were very different from conventional studio yoga classes. Expanding beyond the physical practice, they included sermon-like discourses. I argue that this makes transformational festivals and the yoga classes therein under-recognized institutions of unchurched religion. Also, the spiritual rhetoric in these fields—and particularly in yoga classes—often focuses on questions of authenticity, which relates closely to how white yoga teachers locate themselves as representatives of South Asian cultural and spiritual traditions.

Both the yoga mat and the festival environments are active spaces of introspection wherein participants look inward and cultivate spiritual experiences. They are also extraordinary opportunities for social bonding and connection with community. Both endeavors generate affective feelings of freedom, which I found was the most commonly iterated shared experience among participants. This affective expression of freedom exists in dialogue with neoliberal propensities to attain freedom through the pursuit of self-cultivation, and in contrast to freedom work for social justice in society at large.

I wrote this book as a contribution to critical whiteness studies. My research uncovers understudied modes of what Indigenous scholar Aileen Moreton Robinson calls white possessivism, focusing on how such ideological practices reinforce and perpetuate the majority whiteness of SBNR communities.

But White Utopias also expands beyond blanket critiques and stays true to the humanizing practice of ethnography. I show how my informants have very real spiritual aspirations and communal connections in these contexts. Many of the practitioners engage deeply with ascetic and mystical practices, actively deconstructing conventional conceptions of the self and reconstructing anew with tools drawn from a variety of religious forms. Deeply introspective, they explore interior metaphysical spaces and engage in spiritual journeys in collaboration with like-minded others. In so doing, I argue that they build an ideological commons through which they can grow collectively and in community.

What emerges is a story that is both critical and empathic. It recognizes the inherent violence of cultural appropriation, as practitioners co-opt spaces of cultural representation usurping people of color and then also how these populations level a serious critique of western civilization, including current hierarchies that support white supremacy. I conclude with the understanding that so long as they do so from ideological comfort zones of predominantly white homogenous spaces, they limit their potential to imagine spaces beyond white utopias.