By Katherine Smith, author of The Accidental Possibilities of the City: Claes Oldenburg’s Urbanism in Postwar America

This guest post is part of our #CAA2021 conference series. Visit our virtual exhibit to learn more.

Over the last few years, I have been following the developments in American urbanism and the changes to our monumental landscape, from the toppling of Confederate statues, to the various proposals for new designs and strategies that prioritize inclusion and justice. The January 6th insurrection at the Capitol after the confirmation of President Biden and the resulting damage to its sculptures is one of the latest events in this discussion.

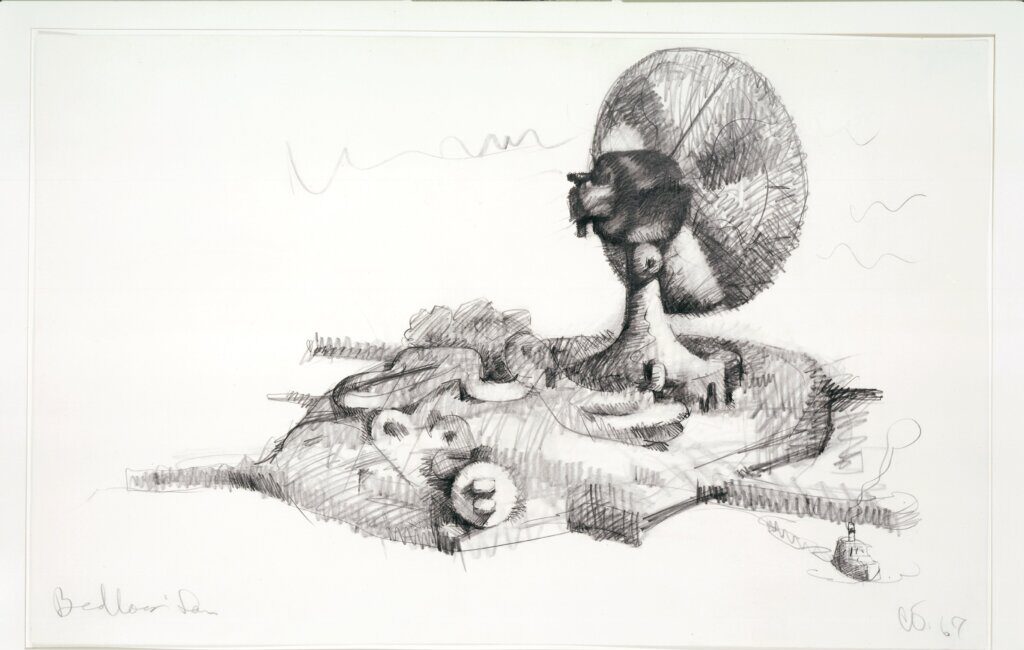

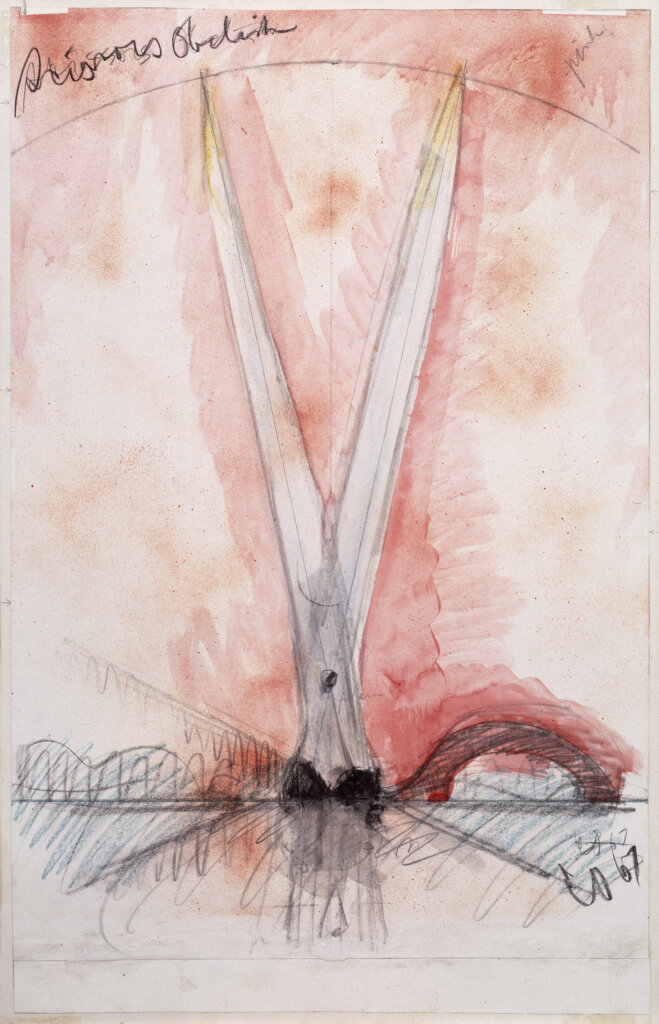

These examples relate closely to Claes Oldenburg’s proposed and realized monuments of the 1960s, when he took aim at some of this country’s most cherished national treasures, creating designs that we might understand in similar revisionist terms. In my new book, The Accidental Possibilities of the City, I trace Oldenburg’s foundational and enduring relationship with the city as a critical perspective on his career, presenting his art as urban theory. My third chapter explores his designs for monuments in New York, which confronted paradigms of modern architecture and urban design and challenged the recent implementation of new cultural programs and public policies in the city. In many proposals, he offered replacements: a fan for the Statue of Liberty and scissors for the Washington Monument. These suggestions had some structural correspondences to the original forms, with the radiating crown becoming oscillating blades (as Susanneh Bieber discusses in her forthcoming book, Construction Sites: American Artists Engage the Built Environment, 1960-1975) and the vertical shaft becoming moving shears. Static structures morphed into dynamic, even dangerous, substitutes – simultaneous elevations of everyday objects and new strategies for public projects. They extended and transformed allegorical and appropriated symbols into modern contexts.

I am not the first to make such assertions about the destructive nature of Oldenburg’s proposals. But only in the days following the Capitol riots have I started to consider the significance of this disposition of Oldenburg’s object monuments in the aftermath of another episode of damage to public monuments. Instead of envisioning monuments that might await their own demolition, disrepair, or dissolution, some of Oldenburg’s proposals altered their surroundings and even threatened inhabitants in various ways. Not only might this aspect of the conceptual designs make them more noticeable to their immediate audience, but it also anticipates and asserts, as it internalizes and perpetrates, common and historical fates of monuments and public sculptures. To this end, Oldenburg offers not just counter monuments, but in some ways, a reversal of monumentality. His approach makes monuments more proactive than retrospective, and more incisive than their playful forms might initially seem.

As the current discourses and political ideologies converge around monuments in the U.S., I reflect also on Oldenburg’s Placid Civic Monument (1967), a 6 x 3 x 6 ft. hole dug and refilled by gravediggers in Central Park on October 1 as part of a municipal show of public sculpture, Sculpture in Environment. The monument was unexpected and complex, even in its day. It was also an unusually abstract, geometric form from the artist, who considers it his first permanent monument. It is paradoxical: an opening and closing, construction and excavation, presence and absence, and, in Oldenburg’s own words, a literal response to the exhibition’s title. Moreover, its horizontal orientation, seeming ephemerality, and malleable materials oppose established elements of monumentality. Its location near the stone obelisk, Cleopatra’s Needle, and behind the Metropolitan Museum of Art, clarify its confrontational stance.