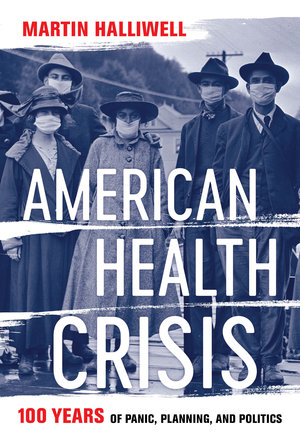

By Martin Halliwell, author of American Health Crisis: One Hundred Years of Panic, Planning, and Politics

This guest post is part of our #OAH2021 conference series. Visit our virtual exhibit to learn more and get 40% off the book.

When I began working on my new book American Health Crisis, I wanted to cover a century of public health governance. I started the story from the development of the U.S. Public Health Service in 1918, when Woodrow Wilson was forced to respond to multiple health threats triggered by the Great War, through to 2018 and a new wave in the seemingly endless opioid crisis. Across these 100 years, there were many stories about lessons learned in the face of crises that quickly vanished as the news cycle sped on and legislative agendas switched focus. Echoing J. Peter Scoblic’s recent op-ed for the Washington Post about the short-termism of crisis response, I saw repeated cycles of panic and planning. Emergency measures typically followed a lapse of attention, but rarely included the long-term vision required to safeguard against future crises.

This pattern is true across many different types of health crises, which I chronicle by the themes of Disaster, Poverty, Pollution, Virus, Care, and Drugs. These crises span diverse geographies and communities of the United States, and allow me to link health emergencies of particular kinds. For example, I link the Great Mississippi River Flood of 1927, the Buffalo Creek flood of 1972 in West Virginia’s mining country, and the devastation caused by Hurricane Katrina in 2005. In each case, what Al Gore calls “a quality of vividness and a clarity of focus” that arrives with a once-in-a-lifetime disaster largely disappeared before lessons about rights, resilience and preparedness were enacted.

I am particularly interested in how the issue of vulnerability keeps arising, in geographically diverse places and at a systemic level for communities and patient groups underserved by the health care system. Sometimes these vulnerabilities hide in plain sight and only become visible in crisis moments, usually with the help of the media. For example, the wider public learned of the long-term health problems experienced by the Oglala Sioux in South Dakota in July 1999 when President Clinton visited the Pine Ridge Reservation to promise economic empowerment, following an earlier Washington Post piece by Jon Jeter highlighting high suicide rates and worrying levels of infant mortality. And forty years earlier, Jack Nelson’s investigative series in the Atlanta Constitution exposed the mistreatment and mismanagement of inpatients in Georgia’s state hospitals. Media attention is crucial for pushing authorities to respond to a mounting crisis, but reporting can also skew the scale of a crisis, or is sometimes reactive while other vulnerabilities go underreported.

Across these 100 years, there were many stories about lessons learned in the face of crises that quickly vanished as the news cycle sped on and legislative agendas switched focus.

Martin Halliwell

Alongside vulnerabilities, I am also interested in health citizenship that can emerge in unexpected ways, especially in crisis situations when communities are often forced to take care of their own health needs as access to basic services collapses. An aspect of what University of California sociologist Robert Bellah calls a “moral ecology,” health citizenship at community-level is vital to prevent health care being determined solely by budgetary priorities. In locating an historical anchor for this moral ecology, American Health Crisis focuses on the progressive health care measures of the Johnson administration’s Great Society initiatives. However, as Julian Zelizer reminds us in The Fierce Urgency of Now, this “period of liberalism” of the mid-1960s was “much more fragile, contested, and transitory” than is often remembered, and arguably over-invested health dollars in ways that were unsustainable long-term. Lyndon Johnson’s emphasis on community health centers and maximum feasible participation frames one version of health citizenship, but in the multi-author The Good Society and other of his writings, Bellah also looks to the “politics of imagination” at a localized level to balance social justice and civil liberties and to “open up spaces for reflection, participation, and the transformation of our institutions.”

The 100 years of American Health Crisis inevitably has a coda, albeit an open one. I had nearly finished drafting the book when reports came through about the first U.S. deaths from the novel coronavirus. The unfolding world emergency was too momentous not to document, especially as the federal government repeated the missteps of earlier pandemics from an early stage. Throughout 2020, the Trump administration downplayed the severity of the situation, whilst shirking responsibilities and looking for scapegoats. The book’s coda reflects on the first ten months of the pandemic, though it will take time for us to fully assess the impact of COVID-19 upon vulnerable communities, as well as the ways that community health citizenship has emerged in its wake.

The century of panic, planning and politics I trace in American Health Crisis is an open history, with future missteps in public health governance very likely. To minimize the extremes of this crisis cycle, we must maintain a strong historical perspective and put the lessons we’ve learned into practice in sustainable ways. There is more hope now than for much of 2020, when mixed messages and data disputes at federal and state levels overshadowed the life-saving work of health care professionals and volunteers. The four converging crises that President Biden has outlined – the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change, structural racism, and economic hardship – all need urgent attention, though none will be easy to resolve. However, with U.S. vaccine rollout at an advanced stage and with a renewed commitment to environmental causes and infrastructural investment, the Biden administration’s social justice agenda might just push the national conversation towards deciding what structural reforms are needed for a more inclusive model of citizenship-oriented care.