As a professor American studies and ethnicity at USC, Natalia Molina has spent her career studying race, citizenship, and the experiences of immigrants in the U.S. Last year, Molina was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship in honor of her “revealing how narratives of racial difference that were constructed and applied to immigrant groups a century ago continue to shape national policy today.”

A veteran UC Press author, Natalia Molina has published three books with the Press. We reached out to discuss the MacArthur award, her current book project, and the relevance of her work —and that of other academics in the field — to the current moment.

Natalia Molina is Professor of American Studies and Ethnicity at University of Southern California and the recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship. She is co-editor of Relational Formations of Race, and author of two award winning books, How Race Is Made in America: Immigration, Citizenship, and the Historical Power of Racial Scripts and Fit to Be Citizens?: Public Health and Race in Los Angeles, 1879-1940.

Congratulations on winning a 2020 MacArthur fellowship! How did it feel to win this award, and how has it impacted your work?

You know, at the beginning, it’s just pure shock. You don’t quite know what to think. I am now five months out from receiving it, and I think I have a better sense of what the award is: it really provides a spotlight on your work.

There’s so much good work out there in academia, but it doesn’t always make it out into the public. It doesn’t always make it outside our universities. So, it’s a valuable opportunity to be able to be in dialogue with the media, and be part of the discussion when there are important stories on immigration bills or how we might imagine a better future. There’s an urgency to the moment now, especially given the protests last summer and in the wake of George Floyd’s death. We have also witnessed the precarious conditions the pandemic has exacerbated, anti-Asian racism, the insurrection at the Capitol. This is the rise of white supremacy. I think there’s more of an urgency for academics to get our work out there and to be part of broader conversations.

“We have witnessed the precarious conditions the pandemic has exacerbated, anti-Asian racism, the insurrection at the Capitol. This is the rise of white supremacy. I think there’s more of an urgency to get our work out there and to be part of broader conversations.”

Natalia Molina

You’ve published several acclaimed books on race, including Fit to Be Citizens, How Race is Made in America, and Relational Formations of Race. What are the central questions that have motivated your research, and what relevant lessons does your work provide for understanding race in the U.S. today?

I think what we saw in the wake of the George Floyd murder and the protests was that people were starting to see how different moments — anti-Asian racism, immigration battles — were connected. We started seeing the way in which our histories are linked to our present and our futures. We see this in the ways that people started linking things like mass incarceration and detention at the border, the ways people started seeing connections in police violence towards black, brown and Asian communities.

These connections are what my work is about. My research looks at how race is relational. By relational, I do not mean comparative. A comparative treatment of race compares and contrasts groups, treating them as independent of one another. But a relational treatment of race recognizes it as a mutually constitutive, and helps us see how, when, where, and to what extent groups intersect. I coined the term racial scripts to highlight the ways the lives of racialized groups are linked across time and space and thereby affect one another, even when these groups do not directly cross paths. Racial scripts expose the connections among racialized groups, and also reveal how race is made by showing how easily racial scripts are adopted, adapted, and applied to different racialized groups.

By seeing the relational nature of race, groups are more likely to see the similarities between them, which could lead to alliances. The lesson is that we can’t move forward unless we move forward together.

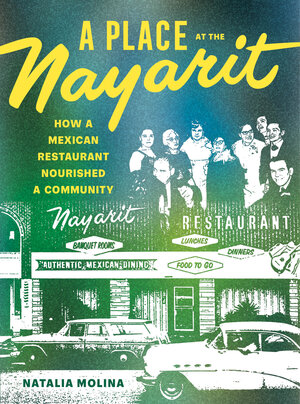

Can you tell us more about your new UC Press book, A Place at the Nayarit?

This book is for anyone who has felt like an outsider but had a special place where they felt like an insider. It’s also the story of how my grandmother, Doña Natalia —who immigrated alone from Mexico to L.A and adopted two children — opened and ran the successful Mexican restaurant, Nayarit, in Echo Park, Los Angeles in 1950’s and 60’s.

The Nayarit was much more than a popular eating spot. Thanks to my grandmother, who also sponsored, housed, and employed dozens of other immigrants, it was an urban anchor that offered Mexican customers a rare opportunity for belonging and a place of their own in Los Angeles. It was a place where ethnic Mexicans and other Latinx L.A. residents could step into the richness of their lives, nourishing themselves and one another.

I weave together detailed conversations with workers, customers, and community members, and explorations of Los Angeles’s formal and informal archives to tell this story. What I hope to illuminate is the many facets of the immigrant experience, from the daily pressures of racism and segregation, to the complex networks of family and community, the cross-currents of gender and sexuality, and the small essential pleasures of daily life.

By seeing the relational nature of race, groups are more likely to see the similarities between them, which could lead to alliances. The lesson is that we can’t move forward unless we move forward together.

Natalia Molina

What do you find most exciting about the field of history right now?

I don’t know if I’d describe it as exciting, but again, there’s an urgency to this moment. When I tell people I study immigration, they say, what a great time to be studying that! But it’s always a “great time.” There are always issues of immigration that are pressing, because we never really address them. There are always issues of race-making that are relevant, because we never really deal with these issues.

But I think there is a different kind of urgency now. Given the Trump presidency, the post-Trump presidency, the pandemic, the protests around the George Floyd murder, there’s a way in which we can’t go back to thinking about “normal” times. Normal for whom? And those of us who study race feel we must harness this moment. We need a plan going forward together.