By Aaron Jackson, author of Worlds of Care: The Emotional Lives of Fathers Caring for Children with Disabilities

Why did he die?’ My youngest daughter, Winter, asks.

I scoop her onto my knee; three years old and already trying to make meaning of her brother’s death. In the years following his unexpected passing, my daughters often blurt out questions and thoughts that sting in their simplicity and truth.

‘Will he be dead forever?’

I look at Winter with an expression of forced equanimity, sadness swelling like a grey sea inside of me.

‘Can’t he just come back?’

It was the summer of 2015 when I began researching how men caring for children with severe cognitive and physical disabilities shape their identities as fathers. Over the next year, I spent time shadowing my participants and interviewing them. My son, Takoda, was four then. Many of the men I came to know were caring for children who were non-verbal. One of the most striking things to arise from my research was the different registers of communication fathers devise with their children in the absence of language. As one father put it, “I really don’t have conversations with him, per se. As his dad, I recognise language through him, in his actions, emotions, and movements. They all express something I can usually recognise.” Accounts like these provide powerful counterexamples to stories about caring for children with disabilities that focus on interpersonal impenetrability.

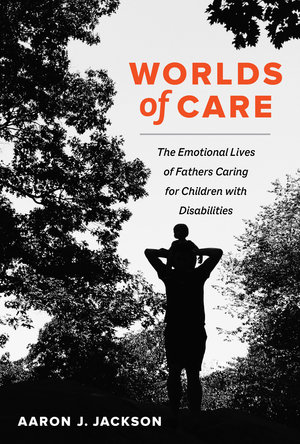

In my new book Worlds of Care: The Emotional Lives of Fathers Caring for Children with Disabilities, I focus on the effect caregiving has on the development of caring identities. Caregiving is difficult and unglamorous, and gender-conforming ideas about how men act and what they should do as fathers can aggravate the difficulty. Men are supposed to be dominant and avoid emotional vulnerability, and women are supposed to be empathetic and avoid dominance. Prescriptive gender stereotypes vary across groups and can change over time. For the men I came to know, fears over being judged as emotionally vulnerable and weak often posed the greatest obstacles to being the fathers their children needed them to be.

One father, Earl, spoke pointedly about how his personal history of gendered experiences had ill-prepared him for fatherhood. Early on after his son’s diagnosis, he said he threw himself into breadwinning instead of caring for his son, attempting to avoid the reality of his new situation. He tried to hide from his grief over lost expectations by shutting down and tuning out. Over time though, the intimacy and deep connection he established with his son began to press upon his identity as a father. As he became more involved in his son’s life and his own marriage, giving and receiving emotional support, his life slowly dropped out of sync with the gender role expectations that had set him adrift from confronting the challenges his family needed him to. He began to embody a better version of himself.

The fallacious opposition between success and love that is central to traditional patriarchal discourse had particular resonance for Earl. There were times when he reflected on mainstream media representations of masculinity and success that contribute to popular understandings of fatherhood. “It’s like whatever is on the TV is what masculinity and success are,” he said. “But success is relationships with people. It’s reaching your potential in life and helping others reach theirs.” He came to see that by helping others grow we often become more responsive to our own needs to grow. “Zachary doesn’t need me more than another dad. He just needs me in different ways. And we have to allow ourselves to grow into meeting those needs and being there for our children.”

Caregiving is difficult, but it resonates with emotional significance. Caregiving can give order and purpose to one’s life. Earl’s story highlights that the meanings that arise from giving our children our unconditional support can help us meet the challenges of sustaining it. In short, fathering is about being there for our children. It’s about loving, nurturing, supporting, and guiding them.

Now that my son is gone, I wish we had spent more time together than we already did. I wish we’d created more memories that I could go on caring for now that he’s gone. This is what I’m thinking when my oldest daughter, India, asks, ‘How long have we not had Takky for now?’

She is six. Her depth of understanding astounds me.

‘Almost a year,’ I reply.

‘And he’s not coming back?’ Winter asks again.

‘No, honey’, I answer. “He’s not coming back.’

I do my best to stumble through another conversation about death and dying. We talk about things I don’t understand, and my daughters ask questions to which I do not pretend to know the answers.

Settled for the time being, the girls and I sit under a duvet on a wicker basket chair on the balcony, facing the ocean. We watch for the sun to rise, finding a sense of him in its fleeting and golden beauty. In the distance the tips of the mountains begin to glow molten orange. After a few moments of silently waiting, the sun nimbly springs up over the mountain tops and begins its fateful arc through the sky. We continue sitting a while longer, warm from the heat of our bodies, each precious breath giving rise to plumes of vapour.