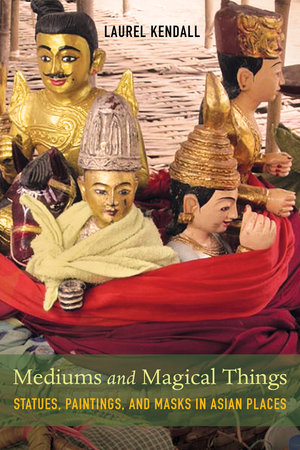

By Laurel Kendall, author of Mediums and Magical Things: Statues, Paintings, and Masks in Asian Places

The paintings of bold-faced gods in the Korean shaman’s shrine had fallen to the floor and stuck together. “They had been fighting,” the shaman said. They had caused her a season of bad luck, ill health, and troubled dreams. These were images that a retiring shaman had given her when she also transferred her gods. The shrine was narrow, and these new images were placed under the existing god pictures. But the new gods and old gods were incompatible. The new ones would have to go.

Paintings fighting paintings? Rivalrous gods fighting each other? A concatenation of the two possibilities? Korean syntax did not provide an answer, but the incident stayed with me like an itch. What made the paintings more than just paintings? What was their relationship to the work of a shaman and the agency of her gods?

Years later, I was in Vietnam with two young researchers. We were interviewing carvers, spirit mediums, ritual masters, and vendors about the images enshrined in temples dedicated to the Mother Goddesses of Vietnam. My colleagues and I asked how Goddess images were made, tended, and might ultimately be disposed of. At the start of nearly every interview, when we explained our project, I told our interlocutors the story of the fallen paintings in South Korea. This seemed to banish any preconceptions they might have had about my worldview as a Western anthropologist by illustrating that I was open to the idea that gods/images could fight with each other.

Our conversation partners responded with their own stories of powerful images and the awful consequences of mistreating them: the statues that were cast down in an anti-superstition campaign and subsequently caused a death by drowning, the motorbike theft at a temple where images had been sloppily installed that same morning, a former iconoclast’s nagging arthritis. They described how a carver’s workshop was a place where magic and fine handicraft mingled to produce a container for a god. The wood was extracted on a lucky day, the ax wielded by a man with an auspicious horoscope. The carvers kept their chests covered even in sticky summer weather, and the entire process was punctuated with prayers and offerings. There were also mediums who argued that none of this was necessary since it was ultimately the ritual master who installed the soul and enlivened the image. On an auspicious day, a ritual master would set the image in place on the temple altar and put a packet of materials, sometimes equated with human organs, in its inner cavity. On another auspicious day, the statue would be enlivened, becoming the material presence of a god or buddha.

Later, I went back to South Korea and asked my shaman interlocutor about the gods/paintings that had fallen to the floor. She replied that yes, these were seats for the gods she served, the locus of ‘the grandfathers and grandmothers’ presence in the shrine. But unlike what I had heard in Vietnam and what I had come to appreciate as a common practice for Hindu and Buddhist statues, I learned that there was no special enlivening ceremony for these gods.

“We cause them to be there, when the shaman sees them before her eyes in the initiation ritual,” she said. It was a telling point: the power and inspiration of the Korean shaman is a consequence of divine favor, something she zealously seeks through prayer and pilgrimage, drawing the gods into the shrine, into the paintings from which they dispense their inspiration. I understood this better now because of a naïve question derived from my experiences in Vietnam. Not all shamans are equally empowered. Some gods are more powerful than others, some are more vividly present than others, and sometimes the relationship goes awry, and the gods depart from the shrine. Instead of a solid statue-container of wood or metal, the painting is a more temporary medium. Old paintings are routinely discarded and burned and the gods invited back into fresh, clean new ones.

Asking about these paintings deepened my understanding of the shamans, who are not passive mediums but active agents of their practice. The story I had taken from Korea yielded new questions in Vietnam and ultimately led me to unexpected answers back in Korea. I began a project on the fabrication and use of ensouled images in South Korea, Myanmar, and Bali, Indonesia. The process of image-making and tending also highlighted distinctions between images intended for a sacred purpose and those hawked as curios, between images in active use and those that have afterlives as art and museum artifacts. The notion that gods become agentive through images is legible throughout Buddhist and Hindu worlds and specialized studies have documented localized and textual practices of fabrication, ensoulment, and tending. Less well appreciated is a sense of how widespread and important these practices are and how they are connected to the work of shamans and spirit mediums in many Asian places.

I lay out these insights in my new book, Mediums and Magical Things: Statues, Paintings, and Masks in Asian Places. The work is imagined as a wide-ranging and vicarious conversation, “a carver in Vietnam told me this,” “a mask vendor in Bali told me that,” “in a South Korean shaman’s shrine, the paintings fought with each other and fell to the floor.” These intersections enable both flashes of recognition and sometimes surprising variations on a common theme. With sufficient resonance to sustain a dialogue, the project tugs against any tidy generalization either across my four cases or as consensus protocol in any local setting. What it does suggest is the vitality of popular practices surrounding ensouled images and the pleasures of ethnographic exploration.