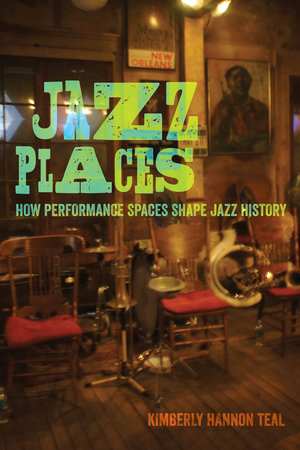

By Kimberly Hannon Teal, author of Jazz Places: How Performance Spaces Shape Jazz History

In some ways, it’s completely unremarkable that pianist Fred Hersch spent his 66th birthday earlier this October recording a live album at the Village Vanguard in New York City with guitarist Julian Lage.

Hersch has been playing and recording at the venue for decades now, and seeing his name on the calendar for a couple of week-long runs every year is expected. Yet this fall’s shows felt a bit more miraculous—the Vanguard had just reopened one month prior following an 18-month shutdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to Phillip Lutz, who reviewed the reopening of the venue for Down Beat magazine, the inside of the venue looked and felt much the same as ever (new air filtration system and vaccine requirement aside). It sounded much the same, too, with 20-year Vanguard veteran Bill Charlap at the piano playing a mix of American songbook standards and jazz compositions, much as Hersh is apt to do when playing in this space. The venue’s online offerings, however, have been completely reimagined, as ramping up its virtual presence was about the only hail Mary available to ensure a physical presence on the other side of the pandemic shutdown that proved permanent for many jazz venues. Now available are a series of recorded streaming sets for purchase and a free “VVTV” channel with video excerpts of music and interviews with artists.

When I had last corresponded with Hersch about my new book Jazz Places during the fall of 2020, a compromised immune system had meant months of almost complete isolation. Seeing pictures of him lounging at a Vanguard table, hanging with fellow musicians Jacob Collier and Micah Thomas after a set, felt like a promising new beginning.

The pandemic has brought the value of live performance into focus through its absence. In Jazz Places, I explore the relationship between the places in which jazz is performed, the way it sounds, and how it is understood. The book offers a snapshot of the live jazz scene in the United States during the first two decades of the 21st century through studies of a variety of venues, from small ones like the Village Vanguard to large ones like Jazz at Lincoln Center and in cities across the country including San Francisco, Omaha, and New Orleans. In particular, I address the increasingly common strategy of presenting live jazz on a non-profit model that provides a public service through philanthropic support, likely a key aspect of how many of the venues described in the book weathered the pandemic.

For many jazz venues, a post-COVID reopening never came. In New York City, The Jazz Standard closed in late 2020, as did Blue Whale in Los Angeles, Twins Jazz in Washington, D.C., and a number of other clubs across the country. Avery Kleinman’s reporting for the Washington Post offers a recent update of the fate of many venues. Some are still in flux, like Shapeshifter Lab, that recently announced a plan to close its current Brooklyn location and move to a to-be-determined new space, and 55 Bar, which, as of late October, is halfway to a $100,000 crowd-sourced fundraising goal that could allow it to remain open.

Although Jazz Places went into production amidst a wave of closures and cancelled performances at all the venues described, they have all begun to offer live music again. The Stone, John Zorn’s New York City venue, has just reopened at half its previous (and already intimate) scale, weathering the pandemic in its new institutional home at the New School in ways that may not have been possible at its original independent location. Shows are now scheduled to run three nights a week rather than six with an audience of only 35 people, and proof of vaccination is required at the door. Preservation Hall reopened on its 60th anniversary in June to similarly reduced and masked audiences. Large-scale venues are also back with new programming and strict safety protocols. Like Preservation Hall, Jazz at Lincoln Center is celebrating a 60th birthday, with artistic director Wynton Marsalis presenting a retrospective of his 40-year career. The Kennedy Center has a calendar of 40 planned jazz performances this season, including a new opera by Wayne Shorter and Esperanza Spalding.

On the west coast, SF Jazz has a slate of concerts curated by their current crop of artistic directors, Ambrose Akinmusire, Terri Lyne Carrington, Anat Cohen, Soweto Kinch, and Chris Potter. Meanwhile, colleges and universities across the country have gradually moved toward more in-person classes and performances after a year of lonely student recitals played to streaming cameras instead of live audiences. While the road ahead remains challenging and uncertain, live jazz is re-emerging across the United States.