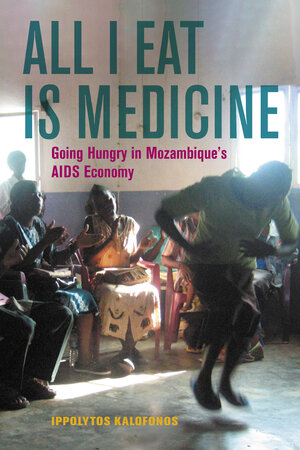

For the 2021 American Anthropological Association meeting, Ippolytos Kalofonos, author of All I Eat is Medicine: Going Hungry in Mozambique’s AIDS Economy, joined us to discuss some of the key findings from his work.

All I Eat Is Medicine charts the lives of individuals and the operation of institutions in the thick of the AIDS epidemic in Mozambique during the global scale-up of treatment for HIV/AIDS at the turn of the twenty-first century. Even as the AIDS treatment scale-up saved lives, it perpetuated the exploitation and exclusion that was implicated in the propagation of the epidemic in the first place. This book calls attention to the global social commitments and responsibilities that a truly therapeutic global health requires.

Ippolytos Kalofonos has an MD from UCSF where he attended the UC Berkeley – UCSF Joint Medical Program and a PhD from the UCSF – UC Berkeley Joint Program in Medical Anthropology. He is currently Assistant Professor in the Center for Social Medicine and the Humanities at the Jane and Terry Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior in the Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences of the David Geffen School of Medicine at University of California, Los Angeles. He is also affiliated with the UCLA International Institute and the UCLA Department of Anthropology. He is a practicing psychiatrist at the West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Affiliated Investigator in the Center for Healthcare Innovation, Implementation, and Policy, Greater Los Angeles VA.

What motivated you to write this book?

From 2003 to 2010, I conducted ethnographic research in Mozambique, following the lives of people living with HIV/AIDS and those on the frontlines of the treatment effort as patients, activists, community health workers, clinicians, and administrators of projects and organizations. This was a key period in the global AIDS pandemic, when treatment for AIDS was finally made available on a broad scale in southern Africa. In Mozambique, HIV was estimated to have infected a staggering 16 percent of the overall population and as many as 25 percent in the principal cities.

In writing this book, I am trying to make good on my obligation to the many Mozambicans who shared their stories with me in the hopes of bringing about some positive change. I want to honor and celebrate the many creative and inspiring forms of solidarity and healing I witnessed, and also point to some of the blind spots of global health interventions that are often too narrowly focused on saving lives without accounting for the other exigencies of survival, such as food and livelihood.

The global AIDS treatment effort during the early years of the twentieth century is often discussed as a remarkable story of contemporary humanitarian intervention on a grand scale. It’s considered a blueprint for successful global health intervention, the start of what has been referred to as “the New Global Health,” challenging the divisions between prevention and treatment, between public health and biomedical intervention, as well as embracing a new era of health activism and the emergence of new public, private and philanthropic global health institutions.

I write against these often-triumphalist narratives. While the vast majority of people I encountered who were on AIDS treatment were grateful for the life it granted them, they also expressed profound ambivalence regarding the treatment programs, often through the idiom of hunger. My book places AIDS treatment within local moral and political economies of care and argues that by disregarding the material realities of collective survival and providing a medical treatment focused solely on biological life, this massive global health intervention established new forms of suffering and subjection. Even as it saved lives, the AIDS treatment scale-up perpetuated the exploitation and exclusion that was part of the propagation of the epidemic in the first place.

What was something surprising that you discovered during your research?

There was a lot that surprised me. One surprise was the way that people living with HIV/AIDS drew on multiple therapeutic traditions and resources simultaneously – from biomedicine, the faith healing practices of African Independent Churches, and longstanding indigenous healing traditions. These eclectic and at times conflicting perspectives came together in groups called associations of people living with HIV/AIDS. People who were experts by virtue of their lived experience with HIV/AIDS supported and cared for each other through education, healing practices, and local activism and outreach. The organizations were often quite closely linked to biomedical services, and the ways they combined those discourses and practices with nonbiomedical and religions practices was striking.

The other surprise was that people reported that the AIDS antiretroviral medications caused hunger. This was not a “side effect” I had learned about in medical school and indeed was not a side effect commonly reported by people taking these medications in the United States. My exploration of what these reports of hunger meant ended up becoming a core theme of the book. I understand the hunger as having both a physiological basis and an existential dimension, as talk of hunger expresses an embodied sense of exclusion and disillusionment. It was not only a persistent sign of inadequate amounts of food, but also a critique of an intervention that disarticulated HIV/AIDS from social and economic realities underlying the epidemic itself. Lifesaving medicines in the context of postcolonial neoliberal inequality exposed people to the brutality of their poverty in new and painful ways, through the irony of eating only ARVs when food itself could indeed have been considered medicine.

What is the main message you hope readers take away from the book?

We should not look to AIDS treatment programs as the template for a new global health. Post-World War II decolonization efforts in the Global South offer better models. Global health should not be driven by an individualistic biomedical and neoliberal approach, but rather by a social medicine that explicitly attends to social, economic, and political determinants of health present within and beyond the clinic. This approach would echo the relational view of disease and care prevalent in central Mozambique, which recognizes that social commitments—rather than isolated individual behaviors or technological innovations—truly determine health and collective survival. The specific social commitments needed in Mozambique and globally are universal access to essential health care and basic income security. And lastly, a global social medicine approach should take seriously, collaborate with, and support local forms of expertise and knowledge.

What are you working on now?

I continue to work as an anthropologist but I am now a clinician as well – I finished my medical training after completing the research for this book. My experience in Mozambique carefully listening to people’s narratives and making sense of them within their social, cultural, and political-economic context led me to specialize in psychiatry. As a psychiatrist-anthropologist, I am adapting a meaning-centered approach to understanding unusual experiences based on principles from the Hearing Voices Movement in a project that draws on the expertise of clinicians, Veteran peer support specialists, and Veteran voice hearers. I am also the lead qualitative investigator of a quality improvement evaluation of a “safe camping” initiative on the campus of the West LA VA. I teach on the UCLA undergraduate campus as well as in the medical school and psychiatry residency training programs.