By Jacob Doherty, author of Waste Worlds: Inhabiting Kampala’s Infrastructures of Disposability

As delegates gathered in Glasgow, Scotland for COP26, waste amasses on the city’s streets. Years of municipal austerity have stretched sanitation services thin in Glasgow, leaving litter, uncollected rubbish, and fly-tipped garbage to accumulate. With the city in the global spotlight, garbage and cleaning workers prepare to strike, demanding better pay and working conditions. After twenty months of a pandemic that has reframed this infrastructural labor as essential work, they demand that the City Council “stop treating our lowest-paid like trash.”[1] Meanwhile, tenant organizers supporting the union cleaned the neglected Govanhill neighborhood and dumped its wastes at the door of the Council, harnessing garbage’s disruptive power to make inequalities a matter of public concern as they called for sanitation justice.

On the first day of COP26, a court in Kampala, Uganda, ruled that that city’s municipal government, The Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA), was responsible for the May 2020 death of a woman who drowned after being washed away by flooding water while walking to work.[2] Climate change has intensified rains in Kampala as changing land use threatens the city’s precious wetlands, once capable of absorbing storm waters. Ruling in favor of the human rights non-profit Legal Brains Trust who brought the case against the government, the court found that the KCCA was negligent in fulfilling its responsibilities. It had failed to properly manage floods and protect citizens because it allowed drains to fill with garbage and left drainage ditches open, exacerbating flooding and creating dangerous hazards like the fatal flood of 2020.

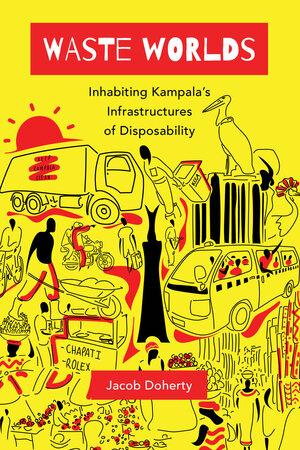

These scenes, more than 4,000 miles apart, reveal some of the shared crises of waste, climate change, and the value of human life in cities around the world that I examine in my new book Waste Worlds: Inhabiting Kampala’s Infrastructures of Disposability. In cities from Glasgow to Kampala, climate change is embodied in particular local manifestations, from floods to air pollution and damaging heat that become the arenas of contestations of environmental justice and responsibility. Waste offers a critical entry point into understanding these processes because of the ways it cuts across scales, connecting everyday domestic life and consumer practices to global supply chains designing, manufacturing, and distributing disposable goods and packaging, to the post-consumer logistics of disposal that, in theory, make waste go away. In doing so, waste creates heterogenous worlds: sites of social and economic life riven with political struggles and the cultural (re)production of disposability. Waste Worlds is an ethnographic study of disposability as it takes shape in Uganda’s capital city.

The treatment of essential workers like Glasgow’s waste workers throughout the pandemic reveals the core paradox of disposability: while disposable goods and people have become collectively vital to the operation of health and other infrastructures, they are functionally essential precisely insofar as they are individually devalued. Through fieldwork with waste collectors and recyclers in Kampala, Waste Worlds shows how the casualized and informal economies of plastic recycling and domestic waste collection are central to the elaboration and maintenance of the city’s waste streams. While they provide an essential supplement to inadequate municipal services in low-income neighborhoods, in wetlands, and at the city’s landfill, they are nonetheless marginalized, if not criminalized, in urban planning: given no place in the clean green future imagined by the KCCA. Following Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor,[3] I argue that these forms of disposability are best understood not as urban exclusion, but as instances of predatory inclusion. They are hyper-exploitative ways of including the urban poor in the infrastructure and metabolism of the city as essential, but devalued, service providers. But as in Glasgow, Kampala’s waste worlds are also sites of contestation, as essential workers refuse and challenge the reproduction of disposability in myriad ways, from rare events like strikes and protests, to more commonplace and subtle strategies of adaptation and inhabitation. In this way, these workers articulate the moral value of their work, establish precarious forms of urban care, and, in so doing, remake the city in their own image.

This book is part of the series Atelier: Ethnographic Inquiry in the Twenty-First Century.

References

[1] https://www.glasgowtimes.co.uk/news/18714081.glasgow-city-council-faces-backlash-dubbing-bin-worker-walk-illegal-strike

[2] https://dailyexpress.co.ug/2021/11/02/court-orders-kcca-to-fix-city-drainage-system/

[3] https://www.nplusonemag.com/issue-35/essays/predatory-inclusion/