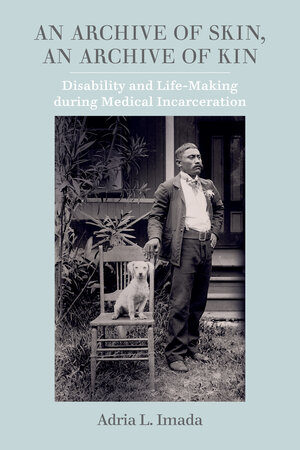

For the annual meeting of the American Historical Association, we reached out to scholar Adria Imada to discuss her new book, An Archive of Skin, An Archive of Kin: Disability and Life-Making during Medical Incarceration.

Adria L. Imada is Professor of History at University of California, Irvine, and author of the award-winning Aloha America: Hula Circuits through the U.S. Empire.

What was the longest and harshest medical quarantine in modern history, and how did people survive it? In Hawaiʻi beginning in 1866, men, women, and children suspected of having leprosy were removed from their families. Most were sentenced over the next century to lifelong exile at an isolated settlement. Thousands of photographs taken of their skin provided forceful, if conflicting, evidence of disease and disability for colonial health agents. And yet among these exiled people, a competing knowledge system of kinship and collectivity emerged during their incarceration. This book shows how they pieced together their own intimate archives of care and companionship through unanticipated adaptations of photography.

How did you become interested in this topic?

My research on visual archives of leprosy incarceration emerges from a longstanding interest in the social and political meanings of photography. My first book on Hawai‘i hula circuits examines popular photographs of hula and tourist entertainment. While thumbing through records at the Hawai`i State Archives, I came across a listing for medical examinations. These boxes turned out to house hundreds of clinical photographs of men, women, and children, taken between 1901 and 1910. The photographs were mostly of Kānaka ʻŌiwi (Native Hawaiians) and recent immigrants to Hawaiʻi – people who’d been arrested as leprosy suspects and later exiled to a settlement. I spent the next few years handling each portrait one by one – many were exquisite, and others painful to see.

So, my book began with the mystery of these photographs and the people within. Who were they and what happened to them? How and why did the territorial government go through the extraordinary expense of photographing and documenting each individual? My book unravels the use and meanings of these health surveillance photographs within the broader social and public health crisis of leprosy in settler colonial Hawaiʻi. To trace the lives of these people and their loved ones, I also delved into many other archives, conducted interviews, and did fieldwork at Kalaupapa National Historical Park (located at the site of the former leprosy settlement).

What was something surprising or unexpected that you learned over the course of your research?

I learned that, despite many advances in medical science and education, medical students and physicians still need better ways of seeing a patient as a person with a full life history. When I teach medical humanities, many of my students don’t immediately understand why someone, especially a person whose family experienced doctors as colonial jailers, may not “comply” with seemingly objective medical advice or authority.

In small and large ways, this book was shaped by what I felt aspiring health care providers needed to know to work meaningfully with Indigenous communities, people who face extreme stigma, and people with disabilities. We each learned much from Kānaka ʻŌiwi families who continued to cherish and touch loved ones with Hansen’s disease, regardless of their external transformation.

Are there any relevant lessons from your book to the current covid-19 pandemic?

During covid, we’ve been saturated with “back to normal soon” messages, whether promises of cures, vaccines, or the reopening of schools and the economy. However, there won’t be a magical return to “normal” life. My book reveals how suffering and stigma linger for decades following a cure. Even after a miracle antibiotic cure for Hansen’s disease was introduced in the 1940s, survivors continued to experience disabilities, chronic pain, and the shame of medical exile. But they also gained empathy, supported each other, and built robust relationships. Learning from them, we’d fare better today by incorporating our ongoing, collective covid experiences into new realities.

What is the main message you hope readers take away from the book?

We’re beginning year three of the covid pandemic, and many of us are feeling the pain of social isolation, interrupted lives, and uncertain futures. However, my book shows how people managed to live through the harshest of medical quarantines and the uncertainty of illness. Hawaiʻi’s medical isolation was the longest in modern history, and thousands suffered from both illness and separation from their loved ones.

Families, however, took pains to remain connected, through poetry, petitions, naming practices, and photography. Incarcerated people also crafted new affiliations and artistic practices over many decades in exile. The many photographs they left are both melancholic and delightful, and I hope others get to encounter their extraordinary work in my book.

What are you working on now?

As an Andrew Carnegie Fellow, I’m researching and writing a book and shorter pieces about ordinary people surviving epidemics in the twentieth century. I focus on the micropractices and creative adaptations of elderly people, young adults, and children during and after calamitous public health and social crises. These hidden survivors include diverse people who may appear able-bodied and those experiencing chronic illness and disability. I’m currently writing about Japanese Americans surviving with psychiatric disabilities in the aftermath of World War II mass incarceration.