By Sarah-Neel Smith, author of Metrics of Modernity: Art and Development in Postwar Turkey

This post is designed as a classroom resource for teachers and students interested in modern Turkish art and larger themes of modernism in a global context. It is adapted from the new release Metrics of Modernity: Art and Development in Postwar Turkey, by Sarah-Neel Smith.

How do economic development programs impact modern art? What does individual expression have to do with the economic fate of nations? And how did conversations between art and economics play out in the global conditions of the post-war period, as international art capitals sprang up around the world from São Paolo to Istanbul?

These are the driving questions of my new book, Metrics of Modernity. But they weren’t always my main focus. When I first moved to Istanbul to work on my dissertation about the art world of 1950s Turkey, I was on the lookout for the kind of mythical research finds I’d heard about in grad school. I envisioned a few revelatory artworks, some pithy artist statements, maybe a manifesto or two––items that would tell me everything I needed to know about the aesthetics of modern Turkish art. But as I combed through archives, conducted interviews, and tracked down paintings, I discovered a surprising fact: artists, gallerists, and critics cared just as much about economics as they did aesthetics.

This discovery became the central theme of Metrics of Modernity. In it, I argue that members of the Turkish art world drew on ideas originating in the economic sphere––concepts that I call metrics of modernity, like privatization, individual consumption, or integration into international markets––to shape their work in the artistic realm. Sometimes Turkish intellectuals used such metrics of modernity to design exhibitions and critique artworks. At other times, the conversation between art and economics played out on canvas, where the question of how to represent a changing national landscape posed an enduring aesthetic problem.

What follows is a brief history of Turkish modernism in three images. It encompasses artworks spanning the Ottoman Empire and World War I up to the postwar internationalism of the 1950s. It also includes a short list of readings suitable for use in a standard survey course about global modern art. Though this class unit focuses on Turkey, it offers a useful point of departure for understanding modernisms across the developing world, from the Middle East to Latin America to South Asia.

“Accessible Academicism”

In 1916, the Ottoman painter Hüseyin Avni Lifij (1886–1927) received an exciting commission: the mayor of Kadıköy, one of Istanbul’s most important neighborhoods, had invited him to produce a large-scale painting for its municipal headquarters. World War I was at its height, and the Ottoman Empire was fighting for the Central Powers. At home, the nationalist movement of the Young Turks, which would successfully establish the Turkish republic a few years later, was gathering steam.

Lifij’s painting gave a human face to the ongoing development of Istanbul’s municipal infrastructure during this tumultuous time. In the foreground, a group of workers lay down city streets with the aid of a modern paving machine (centrally located on the horizon line). These brawny, heroic figures are the catalysts of a larger process of urban transformation in which the ramshackle old wooden houses on the right are being replaced by the imposing modern edifices seen on the left.

Development—The Work of the Municipality was located in a public building, where it was intended to impress its central message upon local citizens using a kind of “accessible academicism,” as the art historian Wendy Shaw calls it. (The rectangular gap at its center is due to its positioning on the wall, where it was mounted around and above a doorframe.) Though Lifij’s painting focuses on a city-wide process of development, it also encouraged its viewers to emulate the heroic workers, and to contribute to the ongoing modernization of Ottoman Turkey at large.

Modernist Strategies & National Art

Seven years after Lifij produced his large wall-mounted painting, and following a bloody war of independence, the revolutionary leader Mustafa Kemal Atatürk established the Republic of Turkey in 1923. Questions of development were still central to public discourse––and to artists––but were now linked to the cause of the nation-state. What should a new “national art” look like?

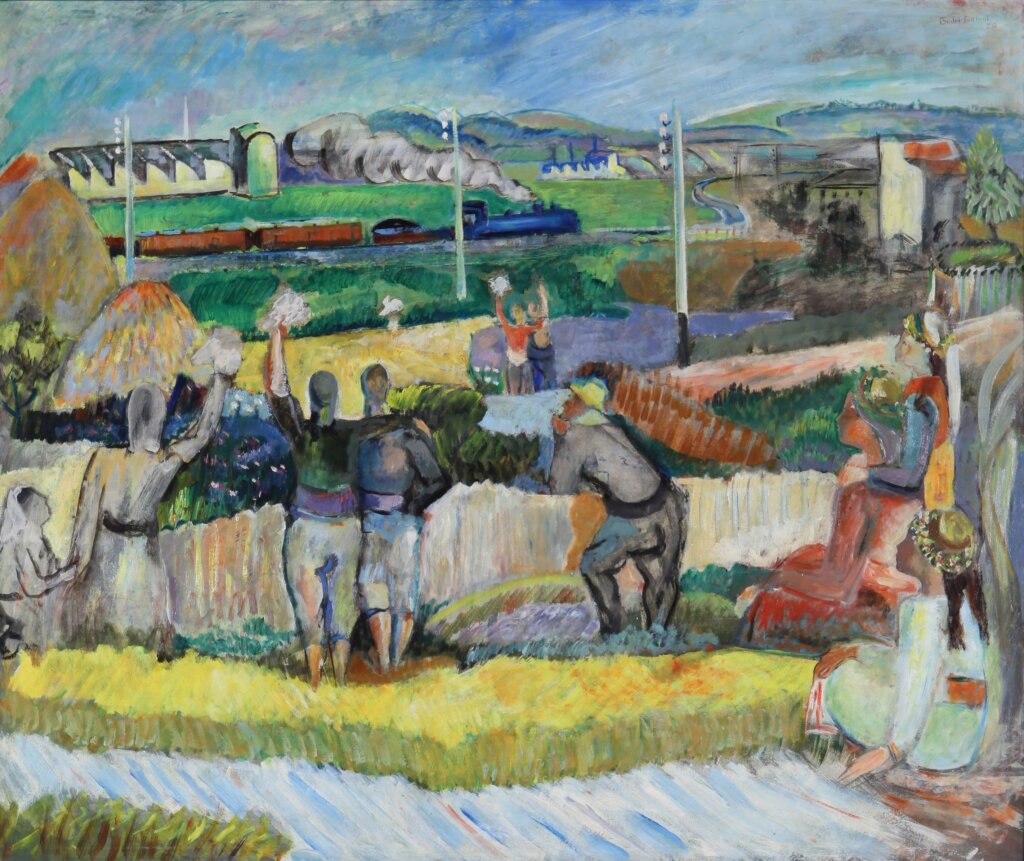

In 1935, a twenty-four-year-old artist named Bedri Rahmi Eyüboğlu (1911– 1975) offered one response to this question. Villagers Watching the First Train is packed to bursting with the iconography of the developing nation. A line of peasants wave energetically at a train that passes in the distance, a mobile emblem of modernity. They eagerly welcome the transition from the agrarian past (represented by the fields in the foreground) to the industrial future (signified by the train and factories in the background). The painting’s patches of interlocking color, which knit together across the surface of the canvas, underscore the theme of the unity of new republic.

Like Lifij, Eyüboğlu focuses on the image of the laboring classes. But his style is markedly different. In contrast to Lifij’s “accessible academicism,” Eyüboğlu’s canvas suggests that modernist strategies––fragmentation of the visual field, non-mimetic color, the manipulation of scale––can be turned toward the larger project of producing a national art.

By 1950, the Turkish republic was nearly a quarter century old and the world had been transformed by World War II. Turkey made a series of definitive political choices to align with the Western bloc and enter global capitalist markets of the postwar period, signing on to the Marshall Plan, and joining NATO and the United Nations.

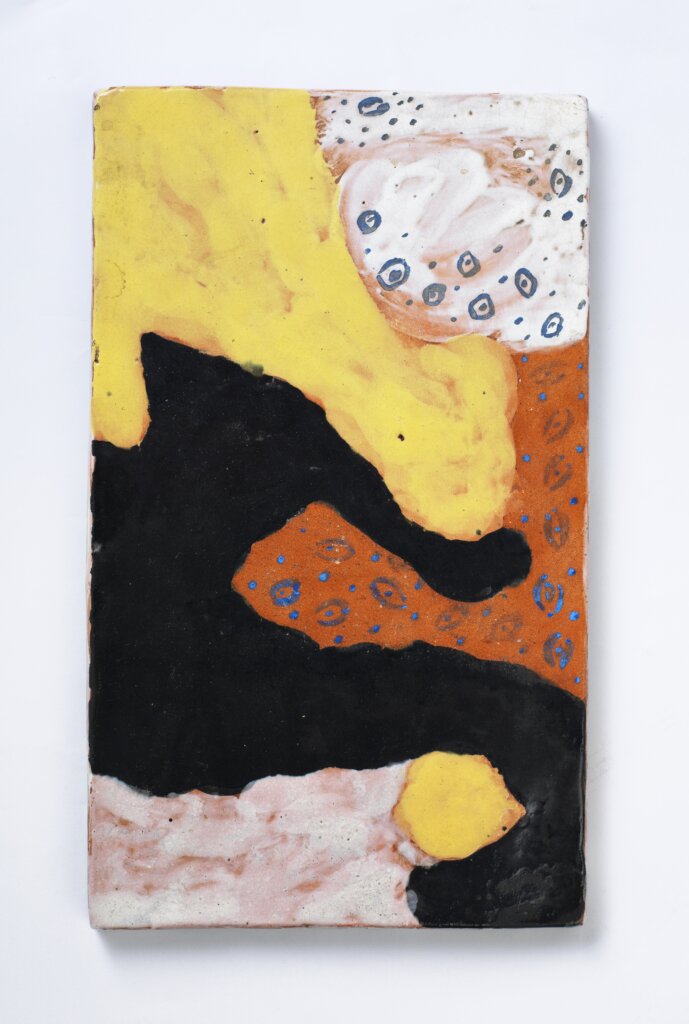

The ceramics artist Füreya Koral (who used only her first name professionally) got her start in this atmosphere of postwar internationalism. While studying in Paris in the 1940s, she began making rectangular ceramic panels whose surface she covered with abstract patches of glaze. These panels participated in international debates about abstract painting that defined postwar painting. But Füreya used clay rather than canvas, and glaze rather than oils––choices which located her work at the intersection of craft and “high” art. In this example, a sinuous field of dense black glaze intrudes from the lower right, threatening to overwhelm patches of yellow, orange, and white. The flurry of blue, almond-shaped forms that rain down from the upper right recall the traditional Turkish boncuk, or evil-eye, motif.

Füreya’s work caught the eye of an official at the Rockefeller Foundation, which funded a range of projects across the developing world. And in 1956, Füreya became the first artist from the developing world to receive a fellowship from the American organization. Though the foundation was impressed by Füreya’s artistic skill, it also saw her as a potential catalyst for economic change: perhaps she could help boost the Turkish economy by adapting her work to mass production.

In 1916, Lifij had deployed accessible academic style, and in 1935 Eyüboğlu had blended modernist strategies with nationalist ideology. Now, in the 1950s, the artist herself was cast as an “agent of development” who could help her country become a major player in the global markets of the postwar period.

Special thanks to Rahmi Eyüboğlu, Hughette Eyüboğlu, and Sara Koral Aykar for sharing their family collections, and to Canan Atlığ and the Istanbul Museum of Painting and Sculpture for permission to reproduce these landmark works.

Further reading

Duygu Demir, “Another Kind of Muralnomad: Bedri Rahmi Eyüboğlu’s Mosaic Wall from the Turkish Pavilion at the Brussels Expo 58,” Thresholds (2018) (46): 120–143.

Bülent Ecevit, selected art criticism columns, 1950–60, “Bülent Ecevit: Art & Politics in the 1950s”

Duygu Köksal, “Domesticating the avant-garde in a nationalist era: Aesthetic modernism in 1930s Turkey,” Vol. 52 (May 2015): 29–53.

Wendy M.K. Shaw, Ottoman Painting: Reflections of Western Art from the Ottoman Empire to the Turkish Republic (London: IB Tauris, 2011).

Hale Yılmaz, Becoming Turkish: Nationalist Reforms and Cultural Negotiations in Early Republican Turkey, 1923–45 (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2016).