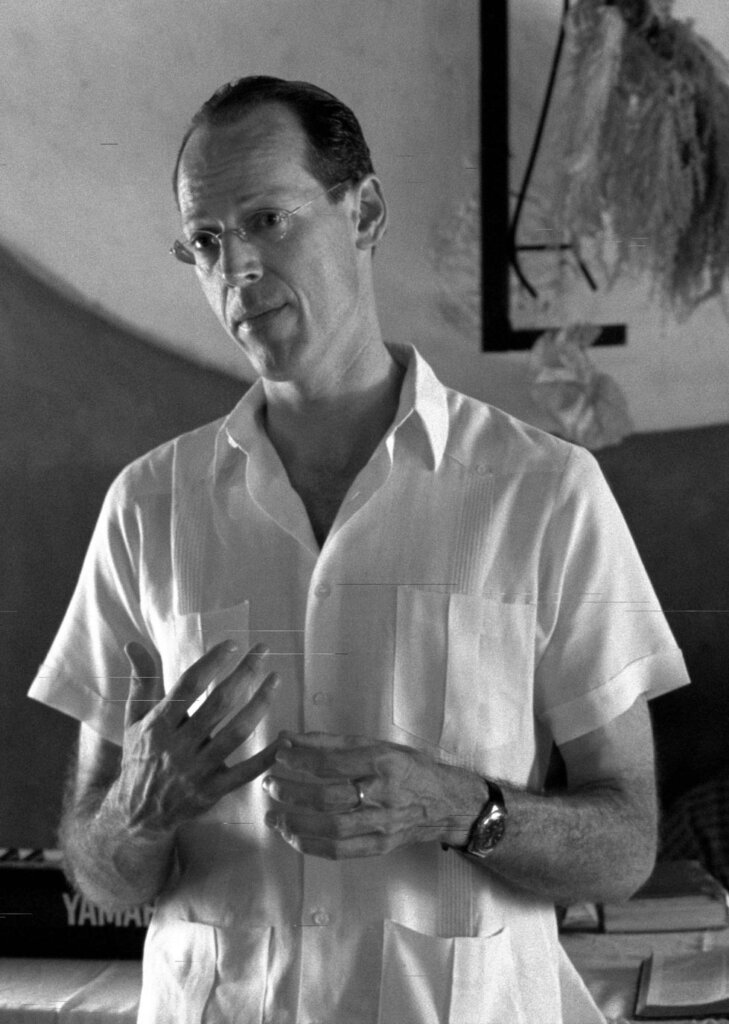

An inspiring humanitarian, doctor, and advocate of global health equity, Paul Farmer leaves behind an immense legacy. With the tragic news of his passing on February 21, 2022, our Executive Editor Naomi Schneider shares a tribute to his work.

By now you might have heard that our author, Paul Farmer, died in his sleep in Rwanda, where Partners in Health had helped to rebuild the medical infrastructure after the 1994 genocide. As his editor at UC Press — we have published six books by him — I want to share my distress and sadness about his tragic, untimely death.

Paul was brought to UC Press by our late colleague Stan Holwitz, who recruited him when he was a grad student at Harvard. Although he earned both a PhD (anthropology) and an MD from Harvard, Paul spent almost all of his time in grad school in Haiti as an activist, fieldworker and nascent physician. From his initial visit as a young student, Paul devoted himself to working on the seemingly intractable issues confronting this under-resourced country: lack of water, hunger, non-existent medical services, inequality, poor treatment by the United States and France, etc. He committed himself to service of the communities around him, and when he won the MacArthur “genius” award, he helped to construct the first hospital on Haiti’s central plateau. The hospital delivered excellent medical care, albeit with the help of Paul “borrowing” medications and services from Harvard hospitals in Boston.

And Paul continued to walk the walk for the next decades, not only in Haiti but in Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Peru, Russia, Mexico, and Boston. Partners in Health, the NGO he founded with his fellow medical student, Jim Kim — who went on to become both president of Dartmouth and the head the World Bank— Ophelia Dahl and Tom McCormack, labored to offer medical services to the most disenfranchised among us in all these places. Partners in Health focuses on the “preferential option for the poor,” i.e. a commitment to seeking equality and dignity for those of us who are usually invisible, marginalized and poverty-stricken. This is a paradigm in which we are all equal — we are “partners” — and it is incumbent on all of us to care for each other.

When I began to develop our Public Anthropology series with a coterie of anthropologists — Paul Farmer, Rob Borofsky, Philippe Bourgois, Nancy Scheper-Hughes, Didier Fassin, Carolyn Nordstrom, Alex Hinton — Paul’s original UC Press editor allowed me to take over. Together with my public anthro folks (the series is now handled with a new group of great editors by our anthropology editor, Kate Marshall, I was able to work with Paul on four books: Pathologies of Power, Partner to the Poor, Reimagining Global Health and To Repair the World. This was in addition to Paul’s previous books, Aids and Accusation and Infections and Inequalities. We know that these books are among UC Press’s bestselling titles but, more importantly, they embody the values that undergird our work at the Press: to serve the community and to partner with the disenfranchised in our fight for social change and human rights.

When we were collaborating on Reimagining Global Health, Paul came to visit the Press offices, and we gathered around him like the acolytes we were — his UC Press fan club.

And Paul was a lot of fun. I’ve spent evenings talking, eating, drinking and dishing with him. He loved an irreverent story as much as the rest of us. I wasn’t just his editor and friend, but also a supporter of Partners In Health, to which I contribute monthly. That too was important to Paul — that his friends supported him in the larger struggles he waged, not just in publishing his books. The stress, workload, and demands of being an icon were not always easy and Paul needed intimacy and caring as we all do.

My last correspondence with Paul was a mere month ago. He ended his message, per his usual style, “with love from Rwanda.”

We love you, Paul. And we will continue to honor, support, and work diligently to embody your values and your life’s work. You gave us so much, dear Paul — we’ll take it from here.

—Naomi Schneider