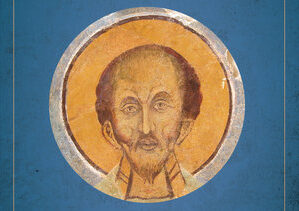

By Blake Leyerle, author of The Narrative Shape of Emotions in the Preaching of John Chrysostom

The problem was clear to John Chrysostom: many in his various congregations were not paying attention. And because they weren’t listening, they hadn’t learned or made much progress. As a professor, this sounds all too familiar to me. Indeed, John often compares himself to a teacher struggling against the usual odds.

But as a highly skilled public speaker, the fourth century preacher also knew what he had to do. The first and most crucial task was to grab and hold the attention of his listeners. The second was to make his message sticky, to do whatever he could to ensure that it would be memorable.

Emotional arousal answered both of these needs. Especially in his homilies on biblical stories, Chrysostom delved into the feelings of scriptural characters. To the spare biblical account, he added luxuriant dialogue designed to surface the thoughts and beliefs that trigger strong feelings and to expose the social interactions that sustain and exacerbate them. To secure the empathy of his listeners, he drew parallels with their own daily experiences and deliberately heightened narrative suspense. His literary sensitivity was extraordinary—he seemed to crawl into the minds of biblical characters.

Even more striking was his insight into his listeners. Instead of focusing simply on eliciting strong, positive feelings from his audience, John understood the galvanizing effect of all powerful emotion: how outbursts of anger, as well as moments of shared sadness and fear rivet attention and leave a durable imprint upon every person in the audience. He knew that students would retain a bright image of that precise emotional moment—remembering what was said, when, and by whom, and what happened next.

Recent studies suggest that stories with a strong emotional impact do more than simply lodge in a person’s memory. They demand to be shared. Bernard Rimé discovered that if a person experiences an emotion during the day that is strong enough that it is still remembered by evening, there is a ninety per cent chance that the person will recount the event to someone else in their immediate circle (“Emotion Elicits Social Sharing of Emotion: Theory and Empirical Review,” Emotion Review 1 [2009]: 60-85). This kind of informal diffusion was one of Chrysostom’s most cherished goals. He wanted his listeners not only to know the scriptures—to remember the narratives, along with the distinctively ethical take-away messages that he had labored—but also to discuss the stories at home and with their neighbors. In a teacherly idiom, we’d say that once he saw them doing this, he knew that education had happened. But as a preacher, he would more likely say that such behavior showed that they had become Christian.

Stirring up his listeners was, in fact, completely central to Chrysostom’s pastoral program. For in his eyes, the fundamental problem confronting humanity was not some inherited stain of Original Sin, as it was for his contemporary Augustine, but rather simple laziness: a basic lack of concern paired with a habitual disinclination to make an effort. The very first step towards any progress in virtue, therefore, consists of stimulating active concern. Emotional arousal—especially if painful—answered this need. It was a supremely effective way to motivate his listeners to take initiative, to get the careless to care.

Making Christian History is part of the Christianity in Late Antiquity series