by Mario Telò, Representations Editorial Board

It is not an overstatement to say that Judith Butler is the most influential intellectual in the world. Indeed, their work has changed people’s lives, including the lives of those who have never even read it. While critical theory aspires to create a better world—more just and more equal—or a radically different one, it is often unfairly accused of having little impact on what some people would call lived experience. Though Butler has never taught in philosophy departments—which in the English-speaking world are informed by common sense and mathematical or conventional logic—there is probably no work of philosophy that has had greater socio-political impact than Gender Trouble (1990). Jack Halberstam—another scholar who has made gender and sexuality central to critical-theoretical discourse while also trying to open it up to popular, non-academic culture—has said that without Butler’s work (Gender Trouble and the subsequent Bodies That Matter and Undoing Gender), “you wouldn’t have the version of genderqueerness that we now have.” Butler, Halberstam says, “made it clear that the body is not a stable foundation for gender expression.” In Gender Trouble, Butler “gave people a way of thinking critically, philosophically, abstractly about what it means to be in a political struggle where the category of womanhood, rather than holding together and cohering, might well be splintering and falling apart.” If the world has become a more welcoming place for queer, gender-fluid, non-binary, and trans people, we owe this change to Butler’s revolutionary vision, to their rigorously deconstructionist pushback against our natural tendency to embrace the comfortable solutions of binarist thinking. In South America, where the debate on gender is particularly heated, Butler has been received as a saint or savior or, conversely, as an incarnation of evil. They have been the target of attacks, physical assault, and death threats during their many visits.

While Butler has attained intellectual stardom, their devotion to critical theory has remained an ethical mission, a practice of kindness, generosity, and genuine care for the other. Butler has spent the past twenty years theorizing vulnerability, precarity, inter- and co-dependency—developing a challenging, cogent, essential conceptual apparatus for combating the hierarchy, violence, and oppression subtending the idea of a self-contained, self-reliant, self-sufficient individual subject in capitalistic society and the neoliberal state.

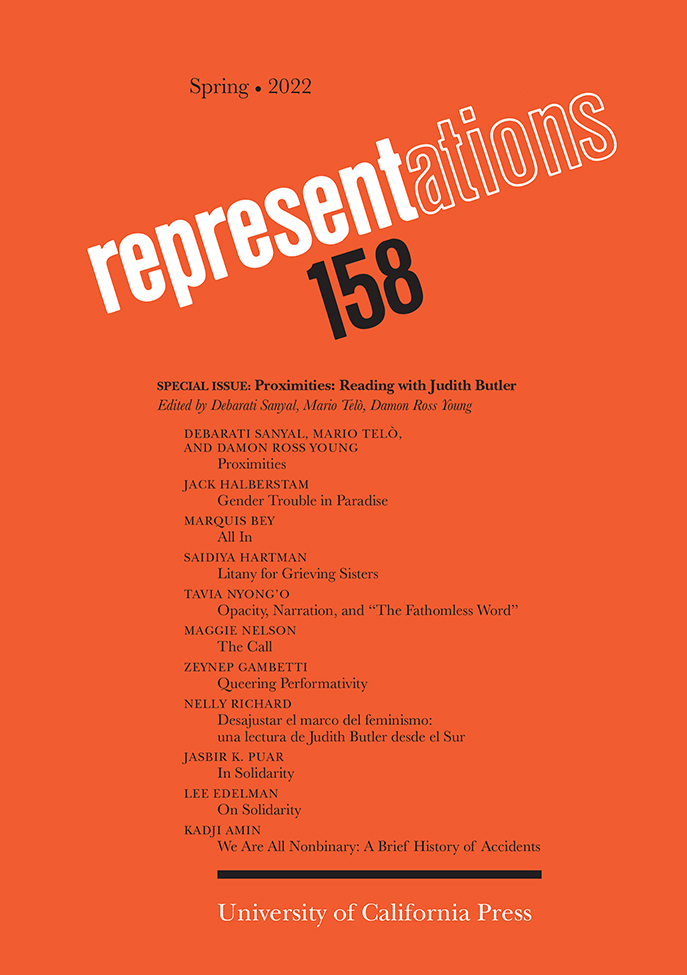

A new special issue of Representations, Proximities: Reading with Judith Butler, collects a series of close engagements—exercises in intellectual and affective proximity—with the writings of Judith Butler. This is not the usual Festschrift, a collection of studies in honor of a scholar, but rather an experiment in communal or even “undercommon” writing and reading. as Stefano Harney and Fred Moten might put it. As suggested in the introduction—which the editors wrote in three separate parts while programmatically concealing individual authorship—what emerges from the collection, and from Butler’s oeuvre and intellectual practice, is that “reading with is never a simple affair”:

Sometimes it has the quality of a “surprising or felicitous contact”; sometimes the reading surprises the reader, and no doubt would (and will) surprise the author of the text that, in its coming into being as text, announces its autonomy from authors and readers alike.

Speaking of the volume’s varied contributions, the introduction notes that they “share in a commonality, constituting a polyvocal and collective tribute to Butler: to their generosity as a reader, interlocutor, colleague, advocate, activist, friend; to their singular contributions to an intellectual world capacious enough to hold open, in [Butler’s] words, ‘the proximity of difference that makes [us] work to forge new ties of identification and to reimagine what it means to belong to a human community.’ ”

Among these contributions, Halberstam explores the problematic appearance of Gender Trouble in the HBO series White Lotus, discussing the book’s enduring demand for an “anti-colonial queer revolt.” Marquis Bey challenges the very notion of the “self” from a trans perspective. Saidiya Hartman meditates on kinship, mourning, and the law through a re-writing of Sophocles’ (and Butler’s) Antigone set in our harrowing times of never-ending racist violence. Tavia Nyong’o interrogates the conceptual connection between “relationality” and “opacity,” ultimately asking what it means to be accountable under the conditions of racialized violence. Maggie Nelson considers the implications of feeling—or wanting to be—undone in our daily lives, and especially in the experience of friendship. Jasbir Puar singles out the proximities between Butler’s work on gender, sexuality, and queerness and their engagements with Jewishness, Zionism, and justice in Palestine. Lee Edelman re-reads Butler’s reading of José Esteban Muñoz’s reading of “disidentification,” taking stock of the debate on reparativity, anti-reparativity, and the negative in queer theory. Kadji Amin urges us to consider the danger of normative reinscription implicit in the assimilation of gender to volitional acts of self-nomination.

Proximities: Reading with Judith Butler is a major event, which the distinguished contributors’ generosity—the most pregnant form of proximity to Butler —has made possible.

We invite you to read the special issue, Proximities: Reading with Judith Butler, for free online for a limited time.

We also encourage you to read Representations‘s virtual issue, Unfixing Gender Studies, a companion to the special issue Proximities: Reading with Judith Butler.

Unfixing Gender Studies is comprised of a set of essays previously published in Representations that resonates with some of Butler’s earliest and most well-known critical interventions in discourses around gender. Read in stereoscopy with Butler’s seminal work on gender, they anticipate and echo the same impulse: that we cannot take gender categories for granted.