By Daniel Morgan, author of Late Godard and the Possibilities of Cinema

There was a time in my early twenties when I had gone a while, probably a year or more, without seeing a film by Jean-Luc Godard. At that age a year felt like a long time. Like many cinephiles, Godard’s early films had been important to my self-understanding as a “serious” filmgoer. I suspect I thought I was now past him, more mature and sophisticated than his hipness or penchant for aphorisms and quotations. But then I reencountered Godard for the first time. I think the main feature may have been Bande à part, and I have no memory of which short film was screened first. But the first images of that short film—some foliage shot on the roof of a building; two people in conversation—struck me with force. This, I remember thinking, this is why you go back to Godard: to see the images and to hear the sounds; they are unlike anything else. A short film, probably made quickly—but such beauty.

Godard died on September 13th, which puts an end to his remarkable output of films and videos over more than six decades. Others have treated this output with more care and depth than I will do here. I will simply say that Godard’s legacy may be measured by the fact that there is no one seriously invested in movies who has not been watching films and videos by Godard for most if not all of all of their adult lives. His passing feels like a gesture of finality that closes out an era.

It’s been striking to see how many of the accounts of his career have been invested with autobiography: it was in this year, in this place, and with this person that the writer saw À bout de souffle, or Sauve qui peut (la vie), or Le Mepris, or any of his other work. Yet that seems to miss the point. We all have many pivotal moments as youthful consumers of art: concerts by bands we grow out of, movies whose limitations we later recognize, and so on. What is so remarkable about Godard is the way that these memories are not isolated, how they become folded into a lifetime of viewing and reviewing. In the week since Godard’s death, I’ve returned in my mind several times to a review John Updike wrote of Henry James’s Portrait of a Lady. It is a review from when Updike was an older man, written with the knowledge that he would never read the novel again—and so the review is haunted by the other times he had read it. Updike remains unimpressed by the archness of the plot. So why come back to it? “Between beginning and end,” Updike writes, “of course, there was marvelous writing.”

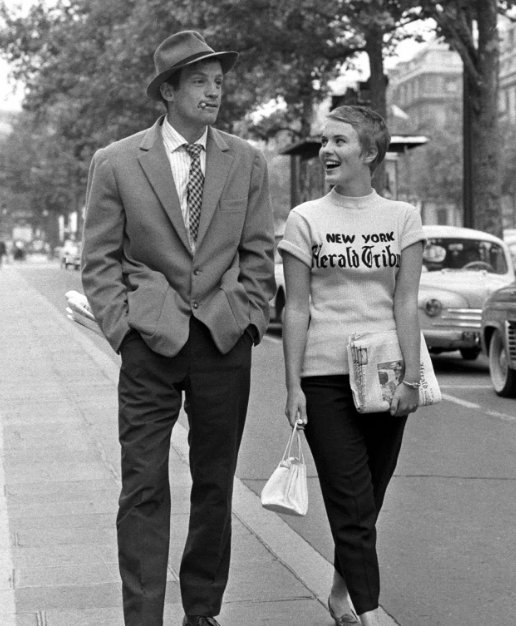

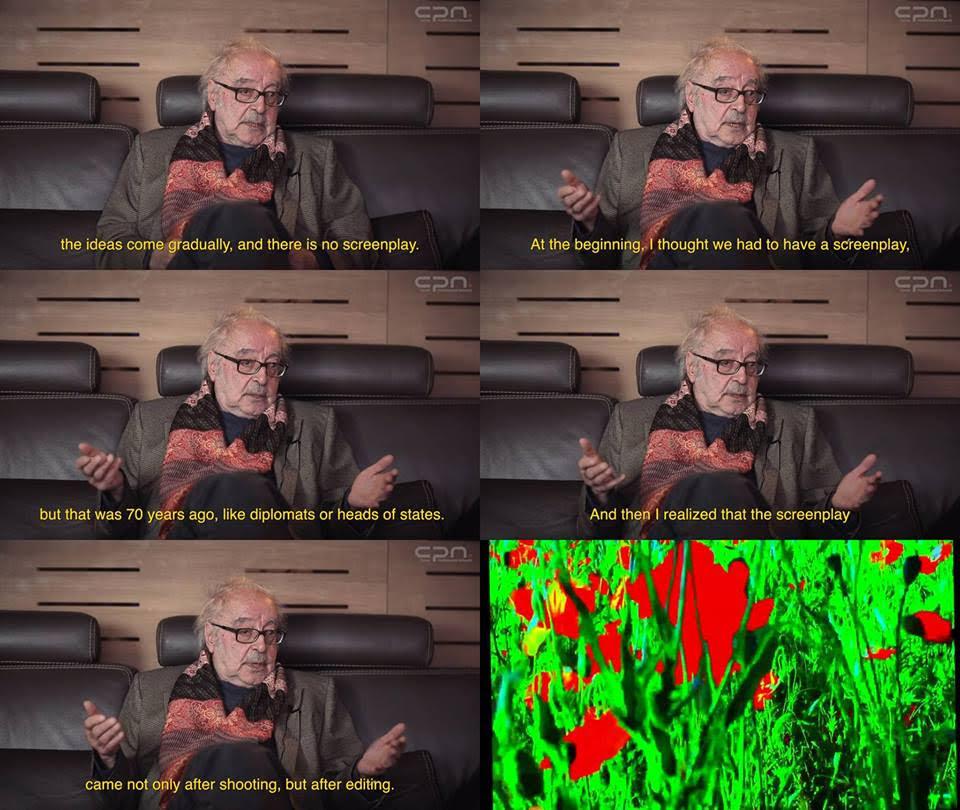

Godard is no novelist, despite his love of literature, and his relation to narrative was, if deep, notoriously fraught and complicated. But there remains, as with James, the investment in form, and the implications and broader significance—aesthetic, cultural, political—to be drawn from it. Some of this is about the composition of images and sound: their arrangement, framing, and interaction. But it is also about experimentation. One of the things that has always stood out with Godard was his refusal to remain content as and where he was. The experiments were technical as much as aesthetic: the jump cuts of À bout de souffle; the long takes of Week-end; the voice-overs of Deux ou trois choses que je sais d’elle; the video monitors of Ici et ailleurs; the stuttered motion of Sauve qui peut (la vie); the flashing superimpositions of Histoire(s) du cinéma. Even at the end, when he used 3D in Adieu au langage, there are two moments where the two cameras that construct the 3D image—our two eyes—split apart, and I remember an astonished and collective gasp coming from the theater as we struggled to process, intellectually but also physiologically, what we were seeing.

For all his bombast, verbal and formal, Godard was also surprisingly delicate. For all the intricate details, he could be fundamentally schematic. Curiously, the combination of general and particular, abstract and concrete, meant that you wound up feeling like you had to look more carefully, to look again. As with James, the care and complexity of the formal qualities of the works meant that they repaid deep and close attention to the specifics of what’s going on. This also seems to be how Godard himself thought about art, and if he framed his art-historical claims in general terms his films and videos often obsessively attended to or replayed small moments from the history of art, and especially cinema, as if to create on their own terms a fantasy of close watching. And that rewatching, whether it was on your own or following Godard’s own paths, was wildly rewarding. Small moments you might have missed, montage sequences that turned out to be wildly allegorical, allusions to the history of cinema—even just the ability, as I said, to see something of extraordinary beauty again, but to know it was coming and so not to be surprised but to allow oneself to flow into its pleasures.

Pleasures is an important word in this context. Much has been, will be, and should be written about the intellectual stakes of Godard’s films and videos, and about their political significance. Few filmmakers have mattered in those ways as much as he did. Yet pleasure suffused his work, animating these ideas and keeping viewers going. One of these pleasures, surely, was the humor. Godard could be, and often was, extremely funny. He had a talent for physical comedy, something that was apparent in his appearance in Agnès Varda’s Cléo de 5 à 7 but which came to be a part of his persona—I think here, too, of the lovely play around American slapstick comedy in Soigne ta droite. There were also verbal games, from the “allons-y Alonso” of Belmondo in À bout de souffle to the typographic word play of Histoire(s) du cinéma. Sometimes the jokes were wonderfully bad: Hélas pour moi, featuring Gérard Depardieu, highlighted the “dieu” and “God” in the opening credits; or in Adieu au langage, “2D” was printed on the screen and then, suddenly, “3D” popped up out in front of it.

Godard was not the perfect filmmaker. That was part of the appeal. The films and videos often have dead zones, stretches of time where nothing quite clicks. He made works as if to record his thought process, to think through ideas in an audio-visual form—if it did not always work, often the result was spectacular. To lose Godard is to lose one of the most fundamentally interesting and curious of the thinkers in cinema; to lose the person who consistently explored what cinema was, had been, and could become; to lose an artist in whom aesthetics and politics could never be separated. For years, the pleasure of going back to Godard has been to trace the process of his thinking, and to do so in the knowledge that he was still working and thinking, still making new things. Now what we have left is only the return. It is to our great fortune that the journey we have already taken has been so extraordinary, and that there are still so many places to go—so many things to see and hear and think—even as we go back over terrain we already traversed.