By Elaine Lewinnek and Thuy Vo Dang, co-authors of A People’s Guide to Orange County

Former President of the Western History Association Patricia Nelson Limerick famously wrote of California and the American West, “In a society that rested on a foundation of invasion and conquest, the matter of legitimacy was up for grabs.” Limerick raises the important question of who can claim to be a real Californian, a real Westerner, or a real American? She notes that this is both a historical and political question. For us, it means that western history and California history is public history.

Our recent book, A People’s Guide to Orange County, responds to this question by redefining the public image of Orange County. Our book begins:

“Home to Disneyland, beautiful beaches, neo-Nazis, decadent housewives, and the modern-day Republican Party: this is Orange County, California, in the American popular imagination. Home to civil rights heroes, LGBTQ victories, Indigenous persistence, labor movements, and an electorate that has recently turned blue: this is the Orange County, California, that lies beneath the pop cultural representation, too little examined even by locals.

First advertised on orange crate labels as a golden space of labor-free abundance, then promoted through the reassuring leisure of the Happiest Place on Earth, and most recently showcased in television portraits of the area’s hypercapitalism, Orange County also contains a surprisingly diverse and discordant past that has consequences for the present. Alongside its paved-over orange groves, amusement parks, and malls, it is a place where people have resisted segregation, struggled for public spaces, created vibrant youth cultures, and launched long-lasting movements for environmental justice and against police brutality.

Memorably, Ronald Reagan called Orange County the place “where all the good Republicans go to die,” but it is also a space where many working-class immigrants have come to live and work in its agricultural, military-industrial, and tourist service economies. While it is widely recognized for incubating national conservative politics during the Cold War, recently the legacy of Cold War global migrations has helped this county tilt Democratic, in a shift that has national consequences. It is a county whose complexities are worth paying attention to…..

Genevieve Carpio explains that an “Anglo fantasy past” suffuses much of Southern California’s heritage tourism, showcasing Anglo pioneers while obscuring the nonwhites who have also been here all along. Indigenous, Asian, and Latinx people have been part of Orange County since its beginnings as a county. During the early years of European settlement, it was people of color who constructed the irrigation canals, planted the fields, built the railways, and picked and packed the crops. They also faced widespread dispossession, from Tongva and Acjachemem territories, to the nineteenth-century Chinatowns in Anaheim and Santa Ana, to the early twentieth-century Mexican American citrus worker colonias.”

Importantly, Juan de Lara observes that working-class people of color have been pushed off the land and out of public memories in two related dispossessions, one geographic and one discursive. Our book is an effort to address that discursive erasure.

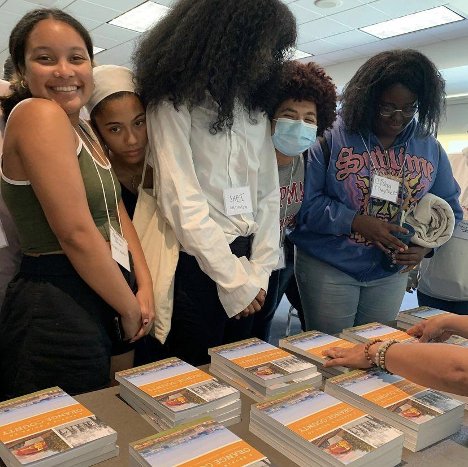

But we also recognized that to help change the public narrative of Orange County, we needed to actually get our book out into public spaces and public discussions. We established an Instagram page for our book and accepted as many speaking invitations as we could. This year, we gave more than thirty book talks. We spoke about our book at public libraries, local stores, retirement communities, one middle school, and every university in Orange County – though not yet every community college. We are proud to have been invited to speak (in English) on both Vietnamese-language Little Saigon Television and Spanish-language Radio SantAna. We also worked with KCET/PBS SoCal to share our book’s insights with a wider audience. At each book talk, we keep learning and inviting our interlocutors to create their own scholarship, too.

Co-writing a book helps make all this outreach possible because there are three of us. Our book’s geographic focus also helps, because there are very few academic studies of Orange County and it turns out there are many people who hunger to better understand the diversity of this space’s past and present. But this also goes beyond Orange County. Our colleagues in the South El Monte Arts Posse inspire us with their mural ideas, poetry, digital archives, exhibits, and other community-based interventions in public memory. From the Los Angeles Urban Rangers to the L.A. Mayor’s Office Civic Memory Working Group, southern California has models of historians and artists creatively engaging our diverse past in order to better move into our future.

We are particularly excited to bridge the divide between high schools and colleges. We connected with groups offering professional development to K-12 teachers and created workshops to encourage diverse educators to use our book in their classrooms. A People’s Guide to Orange County already includes an appendix of lesson plans written by high school teachers that will soon be supplemented by a collection of online lesson plans created in partnership with Educate to Empower and the Heritage Museum of Orange County. We hope this becomes a model for more academic projects.

In this historic moment, when ethnic studies curriculum will soon be required in all California high schools, there is a need for those of us who study the past inclusively to reach out to those who will soon be required to teach more inclusively. It was a quarter-century ago when Patty Limerick raised the question of legitimacy in her article, “Will the Real Californian Please Stand Up?” Now, a new generation of California scholars can stand up.