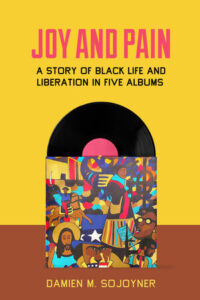

Joy and Pain: A Story of Black Life and Liberation in Five Albums is a poignant account of how the carceral state shapes daily life for young Black people—and how Black Americans resist, find joy, and cultivate new visions for the future.

At the Southern California Library—a community organization and an archive of radical and progressive movements—the author meets a young man, Marley. In telling Marley’s story, Damien M. Sojoyner depicts the overwhelming nature of Black precarity in the twenty‑first century through the lenses of housing, education, health care, social services, and juvenile detention. But Black life is not defined by precarity; it embraces social visions of radical freedom that allow the pursuit of a life of joy beyond systems of oppression.

Damien M. Sojoyner is Associate Professor of Anthropology at the University of California, Irvine. In addition to Joy and Pain, he is also the author of First Strike: Educational Enclosures in Black Los Angeles.

What motivated you to write Joy and Pain? How does it build on your research interests?

I have been interested in movements against the prison industrial complex for quite some time. In many ways, Joy and Pain follows the intellectual impetus of my first book First Strike, which examined the multifaceted connections between public education and the carceral state. Joy and Pain follows a similar multiprong trajectory in that it explores how the carceral state is connected to multiple state structures, including housing, health care, education, and the non-profit sector. It’s very much informed by movements to abolish the prison industrial complex.

The Southern California Library is the intellectual and political hub of the book. This allowed me to show the complex manner in which Black radical thought — which flowed through the archives at SCL and the knowledge traditions of the community immediately surrounding SCL — organized against and conceptually framed the prison industrial complex as a set of relationships that could be studied and dismantled.

Your book uses a unique structure — organized into “five albums” with chapters representing “a sides” and “b sides.” Can you tell us a little more about this structure and why you formatted the book this way? How did it help you explore carcerality in a unique way?

Music is ever-present in the book. It serves as both a backdrop and a major conduit for understanding the nuances of Black study. It was impossible to walk into SCL and not hear the likes of John Coltrane, Erykah Badu, Jill Scott, Charles Mingus, or Frankie Beverley and Maze (shout out to Maze!). It could be five people in the space or 105 people, music was always everywhere. So, there was not a separation between “music” and “archival collections.” It was all a part of the Black ontological experience.

This was also evident in the stories of the main interlocutor of my book – Marley. Marley loves music, and not just as a fan of a particular artist or format. To Marley, music is a form of energy that can galvanize thought and people. He is constantly working on a variety of musical projects, plays several instruments and has a very distinct delivery and voice. Yet he is not exceptional; he is representative of the power of music to articulate the deep political and emotional capacity of Black culture within the community.

As both a way to pay homage to such a rich Black cultural tradition, and to use the complexity of music to help readers better understand Black study, I wrote the book as a collection of five albums. The collection format helps the reader recognize the multifaceted nature of the carceral state and the fight against it. While the A side explores the emotional drivers of contemporary life within a carceral governance structure, the B side delves into efforts that have called out and studied the prison industrial complex in order to undo its violence against Black communities.

The book focuses on carcerality in Black life, but it also highlights opportunities for joy, resistance and liberation. Can you give us an example of this from Marley’s story?

There is a story in the book where Marley and his friends are organizing a neighborhood event to help people understand the politics of the prison industrial complex. Marley is excited as there is lots of food, music and —as with most gatherings in the neighborhood— it will be a cross generational affair. These types of events are the backbone of collective organizing against the prison industrial complex and of Black liberation efforts in general. It reminded me of stories told by former members of the LA Chapter of the Black Panther Party about how organizing was intimately connected to food, music and the joy of Black life. Marley and his friends and neighborhood are a part of that intellectual and cultural tradition where joy is a centerpiece.

Who did you write the book for?

On one hand, I wrote the book for the Vermont Corridor neighborhood in South Central Los Angeles and in support of the many and varied political projects based in the Southern California Library. They are the generative theoretical base that helps readers understand the many moving parts that are associated with Black life and organizing against the prison industrial complex.

On the other hand, the book is written for those who are inquisitive and serious about the process of Black study. The B side of each chapter is informed by the collections of radical organizers housed at SCL that were used in a series of political education workshops over about two years. I aim to show how Black life is not merely for consumption or voyeurism but provides alternate models for living.

What is the main message that you hope readers will take away from your book?

I hope readers will better understand the complexity of the carceral state as a form of governance, ideology, and way of organizing people’s lives. It’s a system that has a vast impact upon and is entangled with multiple state structures. We see this complexity clearly when looking at Black resistance and study of the carceral state, which demands liberation and rest within an ethos of joy and love.