by David M. Freidenreich, author of Jewish Muslims: How Christians Imagined Islam as the Enemy

Antisemitism is becoming increasingly overt—and so too is its close relative, anti-Judaism. To respond and resist effectively, we need to recognize the differences between these two forms of rhetoric, which are also relevant to understanding Islamophobia past and present.

Antisemitism and anti-Judaism both seek to minimize the influence of “Jewishness” within society, but they do so in fundamentally different ways. Antisemitism condemns what Jews are, while anti-Judaism uses Jews as a rhetorical foil to condemn what certain people do or think.

Antisemites, like other types of racists, allege that Jews are inherently different from non-Jews in negative ways. The prejudices that antisemitic rhetoric reinforces justify discrimination and violence against Jews because they are Jews. Those who employ the rhetoric of anti-Judaism, in contrast, emphasize that Jews and non-Jews are often similar in crucial respects. Anti-Jewish rhetoric urges audiences to differentiate themselves from Jews. Unlike antisemitism, which specifically targets Jews, anti-Judaism targets all who bear purportedly Jewish characteristics, especially non-Jews. Its objective is to cultivate beliefs and practices opposed to those that the speaker brands as Jewish.

Anti-Judaism features prominently within the long history of Christian rhetoric because many Christians defined what it means to be a “good Christian” in opposition to purportedly Jewish beliefs and practices. Medieval storytellers, for example, promoted the veneration of Christ and the belief that the Eucharist transforms a wafer into Christ’s body by alleging (without factual basis) that Jews attacked consecrated eucharistic hosts in an effort to harm Christ.

Today as well, some people use aggressively disparaging rhetoric about Jews in their efforts to motivate fellow Americans or Europeans to support specific candidates or policies: to do or think otherwise, these people imply darkly, would be Jewish. When white nationalists in Charlottesville chanted “Jews will not replace us,” for example, they railed against all who support increasing the size, prominence, and influence of non-white populations within the United States. More fundamentally, participants in the 2017 “Take Back the Right” rally urged fellow conservatives to resist these diversifying trends and, in doing so, to embrace a white nationalist vision of America.

Anti-Judaism, in short, is not really about Jews or even necessarily directed toward Jews, although anti-Jewish rhetoric easily leads to antisemitic acts. In these examples, anti-Judaism is about how to be a proper Christian or American. We need to understand that this rhetoric is about self-differentiation rather than discrimination in order to formulate an effective response: namely, to create an alternative, more compelling vision of what it means to be a good Christian or American.

The distinction between antisemitism and anti-Judaism is also relevant to anyone who cares about anti-Muslim rhetoric because Islamophobia encompasses analogues to both. A prominent definition of this term, “Islamophobia is anti-Muslim racism,” focuses on rhetoric that justifies discrimination through essentialist claims about Muslims. Another type of Islamophobia, however, promotes specific beliefs and behaviors among non-Muslims by associating contrasting beliefs and behaviors with Muslims. Allegations that Muslims do not worship God, seek to destroy Western forms of government, and treat women in an appalling fashion—to cite several examples that emerged in premodern times and persist today—often function as a means of condemning non-Muslims who purportedly bear these characteristics as well.

The first type of Islamophobia, like antisemitism, insists that Muslims are inherently different from non-Muslims. The second type, like anti-Judaism, exhorts non-Muslim audiences to differentiate themselves from a caricature of Muslims. Those who respond to this type of Islamophobia by insisting that Muslims are actually similar to non-Muslims—by emphasizing, for example, that Muslim Americans actually condemned the 9/11 attacks—miss the point. In many cases, anti-Muslim rhetoric is not really about Muslims: Islamophobia can also define, by means of contrast, what it means to be a proper Christian, American, or European.

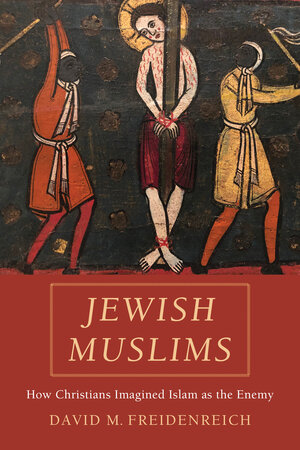

My new book, Jewish Muslims: How Christians Imagined Islam as the Enemy, shows how this second type of Islamophobia works by exploring premodern rhetoric that associated Muslims with Jews. Drawing on the longstanding tradition of anti-Judaism, numerous Christians from Baghdad to Britain and from the earliest encounters with Muslims into modern times alleged that Muslims were Jewish. These polemicists, who knew that their claims were literally false, used this rhetoric to promote their ideas about proper Christianity. Adopt specific characteristics, they warned, lest you, too, come to resemble disfavored outsiders.

The twist here is that Jewish Muslims is not actually about either Muslims or Jews. It is a book about Christians who intentionally misrepresented Muslims as Jewish because they believed that doing so would spur their audiences to become better Christians. By explaining this premodern rhetoric, rooted in the New Testament itself, I hope to help readers more fully appreciate the goals that underpin anti-Jewish, Islamophobic, and related rhetoric within our own societies, so that we can resist accordingly.