by David G. McIntosh with Rena M. Heinrich

The Public Historian’s new special issue “Reckoning with Our Past: California State Parks and the Dark Side of the Conservation Movement,” examines a collaborative effort that began in 2020 between academics, public historians, and representatives from California State Parks to remove a plaque honoring eugenicist and white supremacist Madison Grant and to change the name of the forest named after him. The issue includes articles on Grant’s work as a conservationist and eugenic propagandist; a campaign to have Grant’s monument removed; the response of California State Parks to that campaign; other state parks initiatives to undo past wrongs; and a discussion of other state parks that should be considered for renaming. We asked two of the contributors, David G. McIntosh with Rena M. Heinrich, to share their stories of how they became engaged in the project and what advice they would give to activists undertaking similar work. David begins the narrative . . .

In January 2019, I was six weeks away from advancement to PhD candidacy at UC Santa Barbara with Professor Paul Spickard as my lead advisor. I had converted my notes to MP3s and convinced Paul that going on a fishing and camping trip was a reasonable, if eccentric, proposal. My recent obsession with California’s Heritage Trout Challenge inspired me to choose Northern California as my destination, where I hoped to catch a coastal cutthroat trout in the redwood forests. As it would turn out, rain began four hours into my drive north and did not let up for five days. When I finally arrived at Redwood Creek, just north of Eureka, what I had expected to be a lazy stream was instead a raging torrent. Unable to follow through with the fishing plans as intended, my determination compelled me to try my luck at an alternative spot, which led me to Stone Lagoon. I was rewarded with a torn ACL for my stubbornheadedness while trying to navigate its marshy coast. Unable to immediately make the return journey home due to my swollen left knee and manual transmission, I decided to do some exploration of the area’s history.

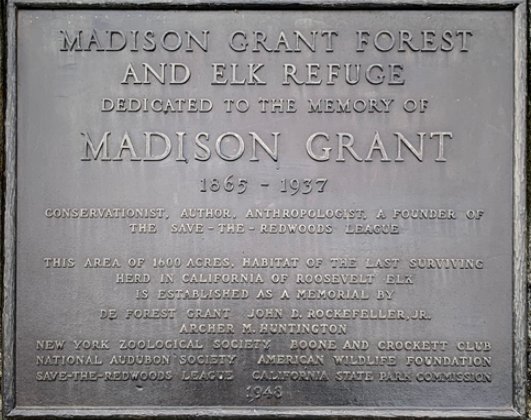

I recalled that Alexandra Stern’s Eugenic Nation mentioned a Northern California monument to Madison Grant, a eugenicist and conservationist whose writings I’d been exposed to in a graduate seminar on racial theory. From my notes, it wasn’t clear if Stern was talking about the monument in the past tense. So, I decided to make the short trek to see what could be found at the site of the monument’s location, which was only five miles north of my original fishing destination. As I pulled to a stop along Highway 1 in front of Prairie Creek, I could already perceive the gigantic boulder—set seventy-five-feet back from the road—that was undoubtedly the surviving monument to Madison Grant. I got out and limped toward this unthinkable marker to have a closer look. I recall feeling a pang of disbelief as I gazed at the towering redwoods, the majestic herd of elk, and the rolling prairie, each tinged by this lingering testament to one of the twentieth century’s most notorious racists. I snapped a couple of pictures, and as soon as I regained a signal, I sent one to Paul. A couple of days later, he forwarded my message along with the image that appears in my article in this month’s special issue to an email list he maintains, which at that time was comprised of just over 150 individuals.

While I had been trained as a public historian, nothing in my background had directly prepared me for how to get started addressing the frustration caused by this enduring injustice. Fortunately, Rena M. Heinrich, who had also studied with Paul and received his email with my picture of the monument, was similarly dismayed. From the moment that Rena, Paul, and I first put our heads together one week later, it was clear that Rena was prepared to address the issue with unmatched tenacity. She immediately wanted to appeal to the state to remove the monument and Grant’s name from the forest. Paul put a preliminary action plan together, which further emboldened her resolve. Though none of us were sure where to start, we were all determined not to relent until we saw the situation rectified. We worked well together, we trusted each other, and we considered ourselves one brain.

Although we did not and could not have anticipated, allies appeared in the most surprising and sometimes unlikely of places. After all, we were not the first to notice the inappropriateness of the monument nor its placement. For example, Jim Wheeler, a longtime National Park Service employee and interpreter in North Coast Redwoods State Parks, wrote to his superiors several years before only to have his protestations largely ignored. (Jim’s 2017 letter appears in this month’s special issue.) While our efforts began with a handful of impassioned historians, the endeavor went on to include the California Department of Parks and Recreation, the Save the Redwoods League, the National Park Service, the Redwood Parks Conservancy, and tribal leadership from the Yurok Indigenous community, among other organizations and individuals.

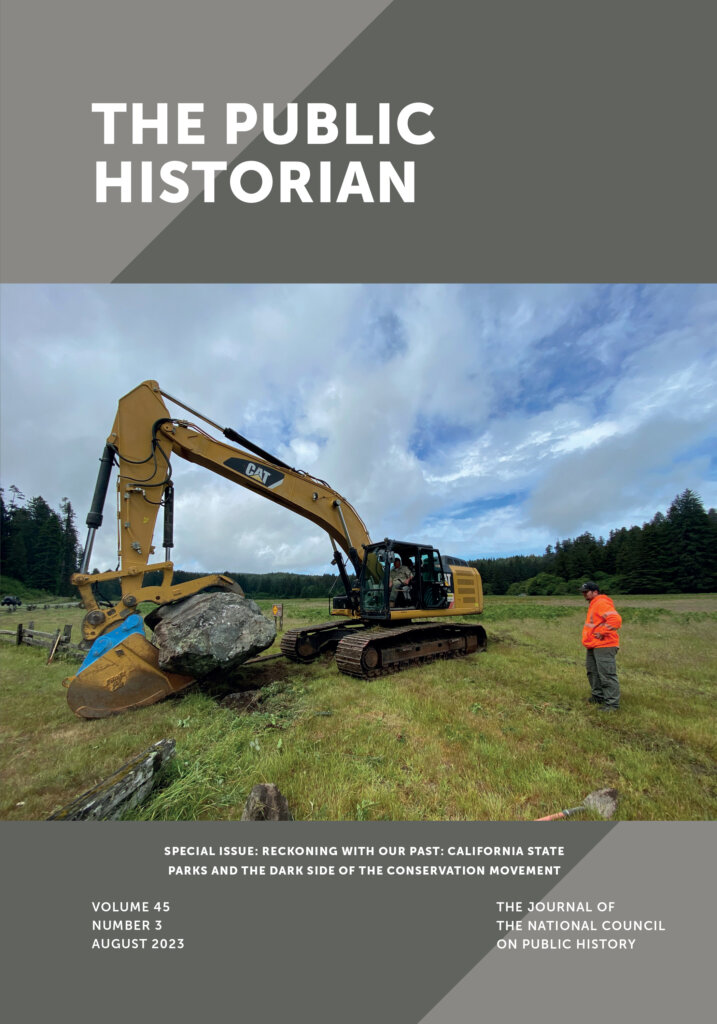

On June 15, 2021, Paul, Rena, and I were pleased to be on-hand for the memorial’s removal ceremony. Dedicated in the place of Grant’s boulder was a new interpretive panel that contextualizes Grant’s influences and reaffirms that California’s public lands are for all to enjoy. Jim was also on-hand, as were two other California Parks employees who were involved in this process, Leslie Hartzell and Victor Bjelajac. The six of us each share individual perspectives of our contributions that led up to this moment in this month’s special themed issue.

My advice to public historians who hope to undertake similar work would be twofold. Grow your network in search of partners, expand it some more, and then keep developing it with additional contacts and potential allies. When Paul, Rena, and I started this project, we didn’t have a clear idea of whom to contact first or how to begin, so we contacted everyone we could think of, including like-minded historians and scholars; politicians; local, state, and national agencies; nonprofit organizations; and more. Start with your own network. Think about folks you already know. Talk to them about it. Make requests. These relationships often lead to others that will help you along the way.

Not allowing yourself to relent is the second piece of advice I can offer. Stay passionate about the goal. While not all of our inquiries led to promising pathways, with each contact we learned new lessons and found ways to realign our energy. We followed every lead and followed up with every inquiry. We sent emails and dropped hard copies in the mail. We continuously learned more about the bureaucratic structure and how to position our inquiry. Having three of us helped us to not get overwhelmed with the multitude of offices with which it was necessary to engage. We never lost the passion. Ultimately, we learned that our contempt for Grant’s memorial was not unique, but it took patient determination to identify and recruit those receptive voices to our cause.

We invite you to read the special issue, “Reckoning with Our Past: California State Parks and the Dark Side of the Conservation Movement,” for free online for a limited time.