By Phaedra C. Pezzullo, author of Beyond Straw Men: Plastic Pollution and Networked Cultures of Care

This month, international leaders and representatives are gathering in Nairobi, Kenya, to finalize a Global Plastics Treaty, which aims to establish an international agreement on how to address plastic pollution. Although in the US we often reduce controversies over plastics to elite lifestyle politics —or at best an injured turtle— plastics have arisen to the top of the global agenda due to the significant threats they pose to public health, the climate emergency, and, yes, marine life. As more of us have come to realize: plastics are profoundly transforming our world and our bodies.

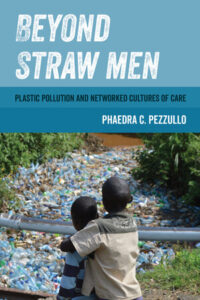

In my new book, Beyond Straw Men: Plastic Pollution and Networked Cultures of Care, I stay with the trouble of trendy hashtag activism and affectively charged controversies about single-use plastics to try to understand why they have become what we call in cultural studies “an articulator of the crisis.” That is, of all issues over the past decade, why are people having heated fights about straws or global gatherings over things like bags and takeout containers? What are the conditions of possibility for so much anger, shame, hurt, fear, guilt, and despair around plastics?

To respond to these questions, I invited environmental and social justice advocates from the US and from the Global South, including Kenya, Bangladesh, and Mexico, to speak on my podcast Communicating Care. As these conversations reveal, single-use plastic bans also have become an entry point into the contested, intersectional environmental politics of today, including carbon-heavy masculinity, carceral policies, planetary fatalism, eco-ableism, greenwashing, marine life endangerment, pollution colonialism, and waste imperialism.

Drawing on these interviews and secondary research, I join those who critique what I call “the plastics-industrial complex,” which includes “industries that extract or manufacture plastics (petrochemical companies), use plastics (including beverage corporations, grocers, packaging companies, and tobacco), and manage plastics (the waste and recycling industry), as well as the institutional apparatuses that enable them, including those that are private (such as advertising firms and industry trade associations) and public (such as governments).” Holding this larger system accountable together enables a more accurate understanding of the conditions of possibility of our current plastics crisis.

By taking seriously hashtag activism and their broader networked cultures of care, Beyond Straw Men moves beyond the initial hot takes to dwell in what is being negotiated in the name of plastics. The title is more than a feminist pun—it foreshadows the ways I grapple in the book with these affective publics without falling for or recreating straw men fallacies, which set up an imagined opposition for the purpose of showing how easily it can be torn down. Rather than fossilizing false binaries, for example, of individual or systemic change, I underscore how advocates against plastic pollution consistently accept and celebrate impure politics, which are imperfect yet impactful.

In conclusion, I amplify four anti–plastic pollution hashtag trends that have critically interrupted the rise of hegemonic plastic propaganda through networked cultures of care. First, there has been increased calls for regulation of #Greenwashing to start to hold corporations—from oil companies to the beverage industry—accountable for when they claim to be “green,” but actually are promoting and enacting practices that actually harm the planet. Second, #BreakFreeFromPlastic Coalition’s annual #BrandAudit has begun collecting waste on our coastlines globally to hold corporations accountable in the court of public opinion for the entire lifecycle of their products. Third, there has been a global movement to imagine a world #BeyondPlastics/ #ÈtèSansPlastique/#SinPlástico through which, I suggest, we might recall “every person is necessary, every plastic is not.” This trend not only suggests new ideas, but also recovers traditions and local solidarity economies through which we can once again live with less plastic. And, finally, there is #Tortuga—a shorthand for the many movements to resist marine life endangerment as a way of recovering the value of radical relationality. As our species’ hubris appears unsustainable, it is compelling to consider how some are (re)connecting with nonhuman kin.

Through these grassroots movements that mobilize social change on and offline, maybe we can ground this Global Plastics Treaty in the voices of those who have been negatively impacted the most by single-use plastics around the world. By reorienting our perspectives, we might find ways to move closer to the broader goals of climate justice and human dignity. And, as my book emphasizes, once the diplomats do their best to address these issues legally, the rest of us will need to do the work of unpacking and negotiating the intense anxieties and affinities we feel about single-use plastics culturally. This is the animating premise of Beyond Straw Men: “To better understand the plastics crisis, I believe we should engage attachments—and detachments—that arise in public controversies over plastics.” This focus on hashtag activism is not a mere distraction, but essential to the change we need:

“Naming uneven operations of power and harm while recognizing those who have successfully transformed the world for the better are critical moves for ushering in a more viable tomorrow. Although we undoubtedly will continue to act imperfectly, insisting that we all are precious and indispensable requires resisting ecological and social detachments through nourishing networked cultures of care. If more of us risk stepping into the fray—as angry, lonely, shamed, and traumatized as many of us feel—we might foster relations that are more egalitarian, biodiverse, and dignified.” (p. 158)