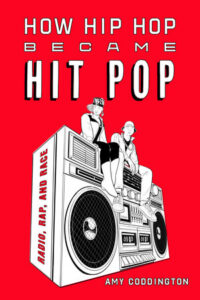

By Amy Coddington, author of How Hip Hop Became Hit Pop: Radio, Rap, and Race

As hip hop turns 50, many mainstream outlets have highlighted how it has utterly transformed U.S. popular culture. And they’re right: look around, and it’s hard to see or hear something that hasn’t been influenced by the young people of color who fashioned, developed, and championed hip hop culture. From Snoop Dogg hosting the Puppy Bowl to Kendrick Lamar winning the Pulitzer Prize, from the global popularity of K-pop boy band BTS’s rapped verses to country artists incorporating trap beats while maintaining some vocal twang, and from rap soundtracking almost every sports arena to breakdancing making its Olympic debut next year: hip hop isn’t so much part of today’s mainstream as it is the mainstream.

How exactly did this happen? How did this minority subcultural movement find its way out of the block and community center parties of the South Bronx and into the ears, eyes, and hearts of people across the United States? My book How Hip Hop Became Hit Pop: Radio, Rap and Race responds to these questions by looking at how one of hip hop’s musical elements, rap, came to be broadcast on U.S. commercial radio stations in the 1980s and early 1990s. In the early 1980s, most commercial radio stations ignored rap, in large part because the genre had come to be synonymous with young, poor Black Americans. But in the late 1980s, previously cautious radio stations began to play the genre, turning LL Cool J, MC Hammer, Bell Biv Devoe, and —yes— Vanilla Ice, into household names. By the 1990s, rapping was everywhere, soundtracking feature films like The Addams Family and House Party, teaching viewers about conflict resolution on the show Kids Incorporated, promoting household products like Sprite and Pillsbury in television advertisements, helping kids learn their multiplication tables on educational cassettes, and entertaining families when they sat down for game night.

Rap changed the commercial radio industry, as its multiracial and multiethnic appeal required those working at radio stations to rethink their programming practices. But the radio industry also changed rap, reframing the genre’s style and substance. For many stations that came to play the genre, rap couldn’t just be the voice of marginalized Black Americans. It also had to fit on their stations broadcasting the sound of young, hip, and majority-white America. Artists grappled with pressure to conform to the mostly white-controlled commercial radio industry’s musical preferences and struggled to maintain the genre’s identity as the radio industry took control of its mainstreaming.

As we celebrate hip hop passing this milestone, it’s important to acknowledge the flipside of its mainstream success. While the mainstreaming of rap has put money into the hands of Black musicians and businesspeople, Greg Tate notes that it has failed to change the material realities of most Black Americans and has not “fully dismantled the prevalent, delimiting mythologies about Black intelligence, morality, and hierarchical place in America.” Instead, hip hop becoming mainstream meant that anyone, regardless of race, could profit from the genre, as the culture was quickly assimilated into the mostly white-owned profit-seeking media industries. Rap can be revolutionary: it acts as a megaphone for marginalized artists to express their inimitable identities. But like all other popular music genres, it does this while selling records, and subsidizing the extractive music industries that were built on the unpaid labor of colonized people worldwide and Black musicians in the United States. Understanding just how hip hop became the mainstream force it is today helps us make sense of this duality, allowing us to comprehend just how rap became the most popular genre in the world without enacting substantive change to make that world more equitable.