College Football, Masculinity, and Race: Q&A with Tracie Canada

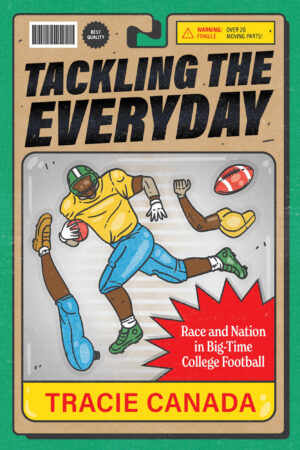

Tackling the Everyday: Race and Nation in Big-Time College Football looks at the broken promises college football makes to most Black athletes and how their reality in this unpaid amateur system can result in dangerous injuries, few pro-career opportunities, a free but devalued college education, and future financial instability. With the 2025 National Championship game days away, author and anthropologist Tracie Canada reveals the ways young athletes strategically resist the exploitative systems that structure their everyday lives.

Tracie Canada is the Andrew W. Mellon Assistant Professor of Cultural Anthropology at Duke University. Her work has been featured in public venues and outlets such as the Museum of Modern Art, The Guardian, and Scientific American.

What is your relationship to college football? Did you grow up watching/going to games?

As someone who has devoted my career to researching and writing about American football and the Black men who play the game, it might be surprising to learn that I don’t identify as a football fan. As a native North Carolinian, I grew up surrounded by interest in and passion for basketball – the other college revenue sport – because of all the great university teams and rivalries in the area. I was a Duke Basketball fan and loved watching games with my family, which later influenced my decision to enroll in the university as an undergraduate. Almost immediately after arriving on campus, my attention shifted to football because I lived in the same dorm as some of the team’s first-year players. Still, when I went to games, it was only to see my friends play. Other people in the stands had to explain what was happening down on the field since football wasn’t the sport I grew up watching.

My current relationship to college football would be best described as one of reluctance. Now, I engage with the sport and watch games not because I’m particularly interested in the gridiron action, but because I’m invested in the Black players who have decided to devote their time and energy to the activity. Since Black men are overrepresented in the sport, they will be in the majority on the field, no matter which team I watch. Any college game that plays on tv will inevitably put a spotlight on Black football players and the dehumanizing practices they endure. Therefore, I tune in to learn how commentators discuss the games and players, to pay attention to what media packages are shown to represent the team and player stories, and to follow the statistics and records that come to define the sport.

What piqued your interest in finding out more about the lived experiences of Black football players? What particularly led you to the college football landscape?

When I first arrived at Duke as an undergraduate student, I was fascinated by how the basketball players on campus were so popular. The basketball and football teams were both predominantly Black teams, the athletes were all marked by their exceptional embodied size, and both sets of athletes dedicated a significant amount of time to their sport, but the hardwood athletes were valued in a completely different way because they contributed to a winning program. I started to pay attention to how my friends on the gridiron were treated, as members of a team that wasn’t as successful and as Black athletes on a historically white campus.

This unique dynamic during my years as an undergraduate initially peaked my interest in learning more about the lived experiences of Black college football players. Once I dug more into the topic, it became clear that there was much more to the story than just what I was anecdotally noticing on campus. It was troubling to learn more about the ways that football players are structurally integral to the entire college sport landscape because of the outsized amount of money their sport brings in for universities, conferences, and media outlets. The whole system depends on predominantly Black football players’ athletic labor and commitment to the game, but they are not compensated in a way that fully acknowledges that contribution. Therefore, I chose to center Black players themselves in my scholarship, focusing on how anti-Blackness, structural violence, racialized exploitation, and capitalist accumulation impact their experiences with the sport and with each other.

College football and football in general have always been characterized by "masculine" attributes. How do you bring a feminist perspective into that arena and why is it important?

American football is often thought of as THE sport for “manly” men to play, at least in the United States. Because it’s rough, gritty, violent, and dangerous, it requires a particular kind of man, who lives in a particular kind of body, in order to persist. What I think is important about my Black feminist perspective is that it allowed me to be sensitive to what I’ve deemed the kindred care that is exhibited and performed in this space. I use this term to describe the care, community, and familial bonds that arise amongst Black players and their kin, specifically their mothers, as they tackle the anti-Black, exploitative, and patriarchal college football system.

In practice, this meant I was attuned to the intimate relationships that form between Black players; the different ways that young Black men can exhibit and display masculinity and care; and the importance of women, particularly Black women, in this hypermasculine space. My own positionality as a young Black American woman researcher also impacted my ability to recognize particularly gendered aspects of the football enterprise that are often overshadowed or taken for granted. Together, this presents a unique perspective about football athletes that incorporates an analysis of care, kinship, support, joy, and playfulness alongside conversations about anti-Blackness, dehumanization, and exploitation.

When strides have been made or attempted in college football to alleviate the exploitative nature of these programs in regards to young Black men, have they been genuine and effective or are they purely optics driven?

I’ll use an example from our recent collective memory to answer this question. Despite the coronavirus pandemic that initially registered in the US in March 2020, young men practiced and travel to run onto college gridirons almost every Saturday in the fall of 2020. At risk with this decision was not only the health of these athletes, but also the potential astronomic fiscal year revenue loss for universities had these teams not played. Simultaneously, the sport was also forced to respond to the police murder of George Floyd in May 2020. In the months immediately following, college teams all over the country took part in performative campaigns to declare their solidarity with their athletes through media messages, public statements from coaches, team-sponsored events, and NCAA approval to include social justice statements on jerseys.

Black football players were uniquely positioned in these twin events because of their overrepresentation in college football. However, any attempts that were made at that time to improve their experiences were instituted through a technique that I call corporeal concern. This is how football teams, coaches, administrators, and institutions of higher education invest in players, especially their bodies, not for their individual well-being, but to secure financial gain from their free labor on the field. For me, this means that any attempts that were made to soften the exploitative nature of the sport at that time were all calculated and strategic, limited by the capitalist and self-serving interests of the college sport system itself. This practice was spectacularly on display in 2020, but is consistently present in the everyday lived experiences of Black college football players.

What needs to be done now and for the future to improve the experiences of these young men?

College football celebrated its 150th anniversary during the 2019 season, so I end Tackling the Everyday by thinking through the ways that the next 150 years of college football could be better. One of the first steps is for a real critique of the contemporary exploitative college football system to be presented to and taken seriously by those who have the power to change it, including administrators at the NCAA and the major conferences, athletic directors, and head coaches.

The initiation of Name, Image, Likeness (NIL) in July 2021 is a step in the right direction, but since it is really only a system that capitalizes on individual athletes’ celebrity, more needs to be done in the way of overall structural change. Prioritizing players’ efforts to unionize, reevaluating how capital flows within the system, removing family narratives from media, and extending medical protections to players post-graduation are all solid places to start. This rethought system should also genuinely support athletes’ efforts in the college classroom and maximize their opportunities for networking that can lead to careers post-football. Finally, because they are particularly harmed by this system, there is the need to continue to center Black players in any conversation about improving the experiences and outcomes for anyone affiliated with the world of college football.