Stonewall was, as the slogan goes, a riot. The uprising began June 28, 1969, in response to a police raid at The Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in New York. After the six days of protests that followed, the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) formed, calling for sexual and gender liberation for all people. GLF’s radical vision also opposed and addressed other social inequalities such as militarism, racism, and sexism. A major criticism of the modern Pride marches is that they’ve become corporate parties that address none of these issues of ongoing discrimination. As corporations glom onto the parades to tap into a demographic of potential consumers, activists have grappled with the morality of these modern marches. While it is not wrong to claim that the past 50 years have marked notable changes in attitudes toward LGBTQ communities, the struggle for liberation continues.

We asked some of our activist-authors to respond to what this 50th anniversary means to them. Here’s what they had to say.

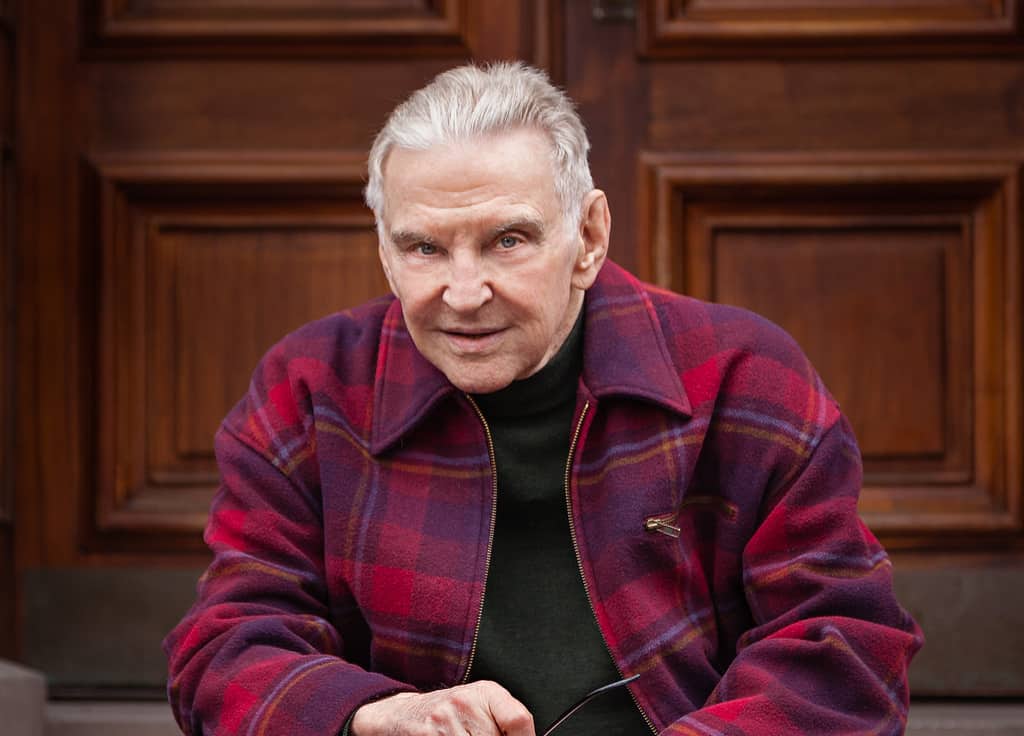

“The emphasis of today’s gay movement on cultural assimilation is inescapably based on the assumption—false in my view—that our mainstream institutions are structurally sound and morally acceptable.”

—Martin Duberman, author of Has the Gay Movement Failed?

“I suspect most gay people will celebrate Stonewall’s 50th anniversary with feelings of satisfaction with what is widely being hailed as the speediest success story in our country’s long history of social protest. The grumblers among us are a decided minority; we’re viewed by the gay majority as professional malcontents, perfectionist dreamers, unable to savor progress even when staring it in the face. It’s a view, doubtless, with some validity. But as an unknown sage said long ago, ‘If you ask for a slice of the pie, you’ll get nothing. If you demand the whole pie, you’ll get a slice.’ Viewed from that perspective, the argument holds that you cannot transform a culture by emulating its values and offering thanks for being allowed to share in them. The emphasis of today’s gay movement on cultural assimilation is inescapably based on the assumption—false in my view—that our mainstream institutions are structurally sound and morally acceptable.”

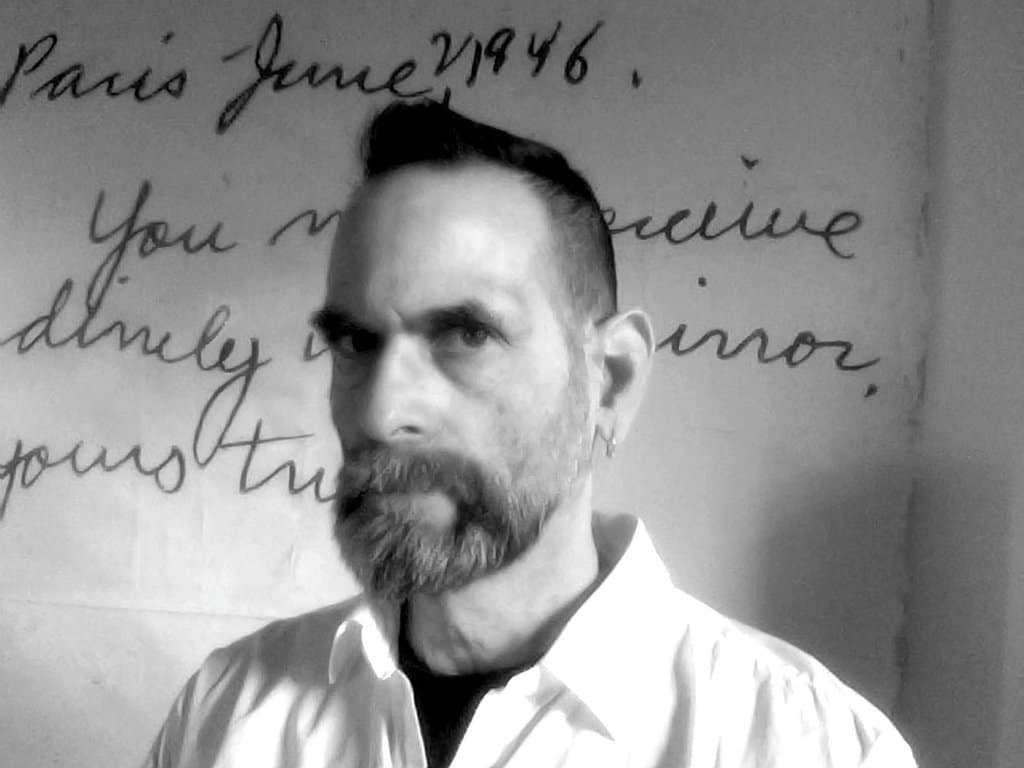

“The increasing commercial sponsorships of Pride implies that assimilation is the logical endpoint of liberation. But assimilation is a fantasia of privilege, the opposite of liberation.”

—Avram Finkelstein, author of After Silence: A History of AIDS through Its Images

“When we designed the Silence=Death poster in 1986 it was intended as the first in a series that would call for increasingly radical responses to AIDS, leading to riots during the 1988 election. On Sunday, millions of people will fill the streets of New York for Stonewall 50th celebrations, and every square inch of public space will be power-washed with rainbow flags, eclipsing the fact that the queer radicals we are there to honor claimed liberation with bricks in their hands. The increasing commercial sponsorships of Pride implies that assimilation is the logical endpoint of liberation. But assimilation is a fantasia of privilege, the opposite of liberation.”

“This anniversary, let’s use queer radical history to reimagine a future in which we don’t have to settle for less.”

—Emily Hobson, author of Lavender and Red: Liberation and Solidarity in the Gay and Lesbian Left

“Commemorations of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer resistance have not always held up the banner of ‘Pride.’ Before the early 1990s, anniversaries of the Stonewall Riots were typically marked as rallies for ‘liberation’ or as ‘Lesbian and Gay Freedom Day.’ These earlier events were both celebrations and acts of protest — ‘marches’ rather than ‘parades,’ with advertisements nowhere to be seen. We need joy, pleasure, and humor; we need rage, solidarity, and resistance. Do we need pride? The history of the gay and lesbian left calls on us to reconsider the sentiments we attach to our queer pasts and futures as well as our present. What happens after liberation? How will we live when we get free? This anniversary, let’s use queer radical history to reimagine a future in which we don’t have to settle for less.”