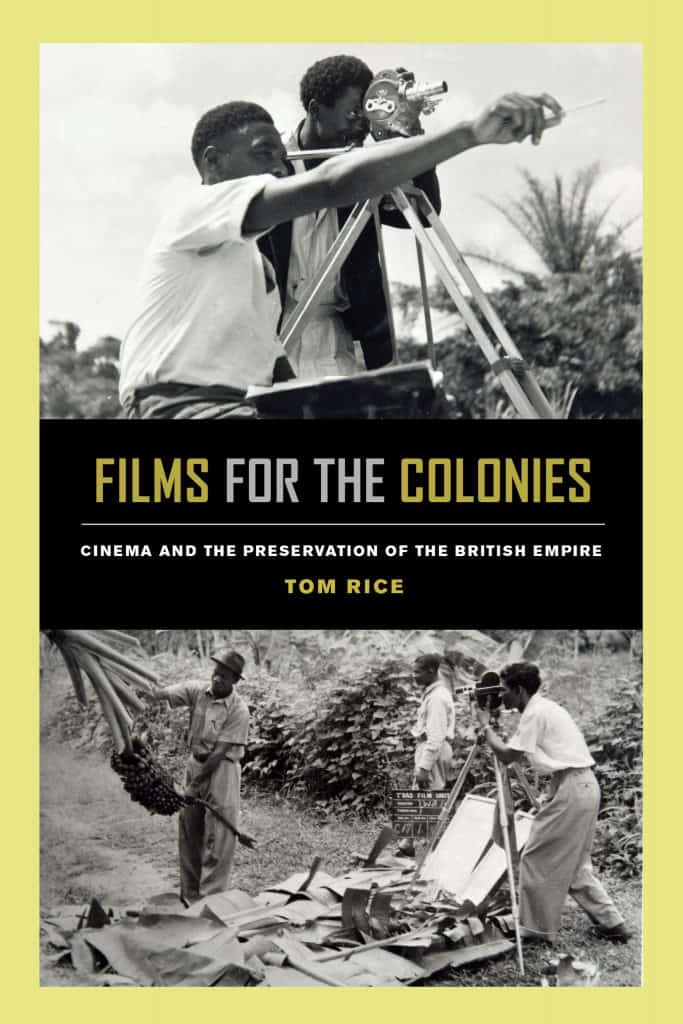

By Tom Rice, author of Films for the Colonies: Cinema and the Preservation of the British Empire

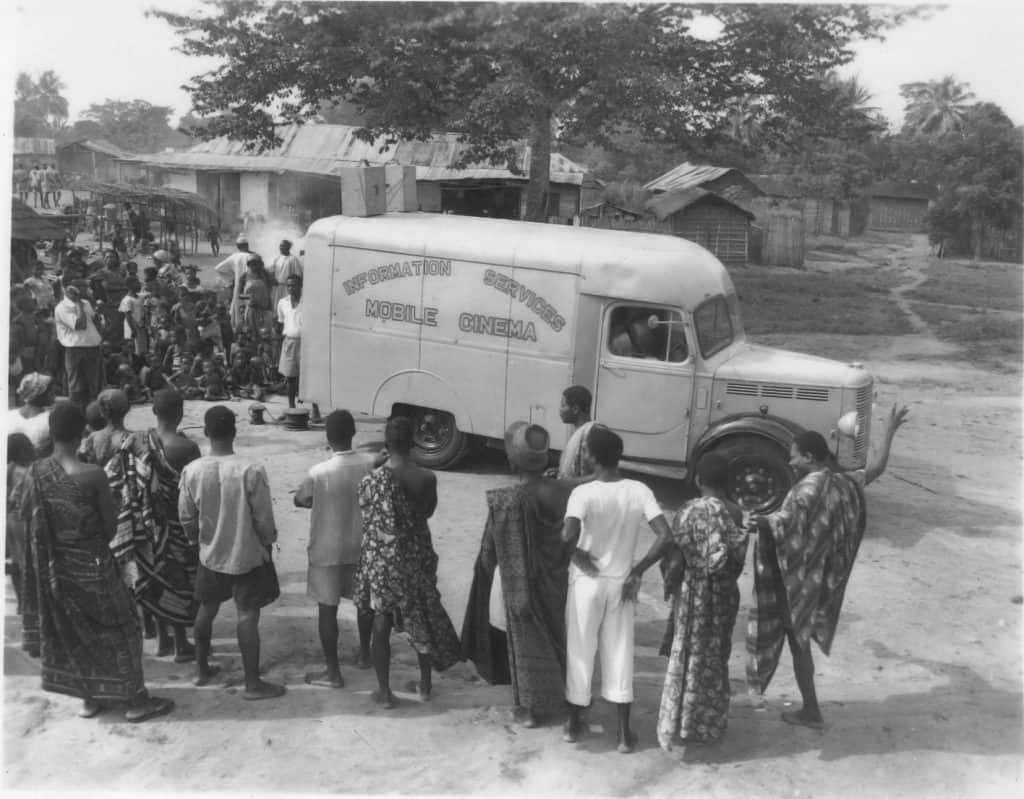

Back in 2007 I began work as a postdoctoral researcher with the British Film Institute and Imperial War Museum in London, cataloguing and contextualising their extensive collection of colonial films. My work allowed me to access and research hundreds of rarely-seen films—from early newsreels to government health films—as I (somewhat inadvertently) became an expert on films about hookworm, basket-making and royal pageants. While providing possibly unparalleled access to fascinating materials in the British archive, it was equally the ‘gaps’ that motivated me with my new book, Films for the Colonies: Cinema and the Preservation of the British Empire. For example, the original project focussed on individual films, and exclusively on materials residing in these major British archives, revealing an often carefully curated government fantasy. So in my new book, I seek to look beyond; beyond the films themselves, to consider the rural mobile film shows and audiences, the role of the local commentator or the related media (from filmstrips to radio broadcasts); beyond the ‘surviving’ films, to consider lost or repressed voices, the aborted productions, failed schemes and long-forgotten units; beyond individual colonies to reveal the networks and infrastructures that facilitated the movement of government propaganda; and beyond Britain, examining the materials found within former colonies from Ghana to Jamaica.

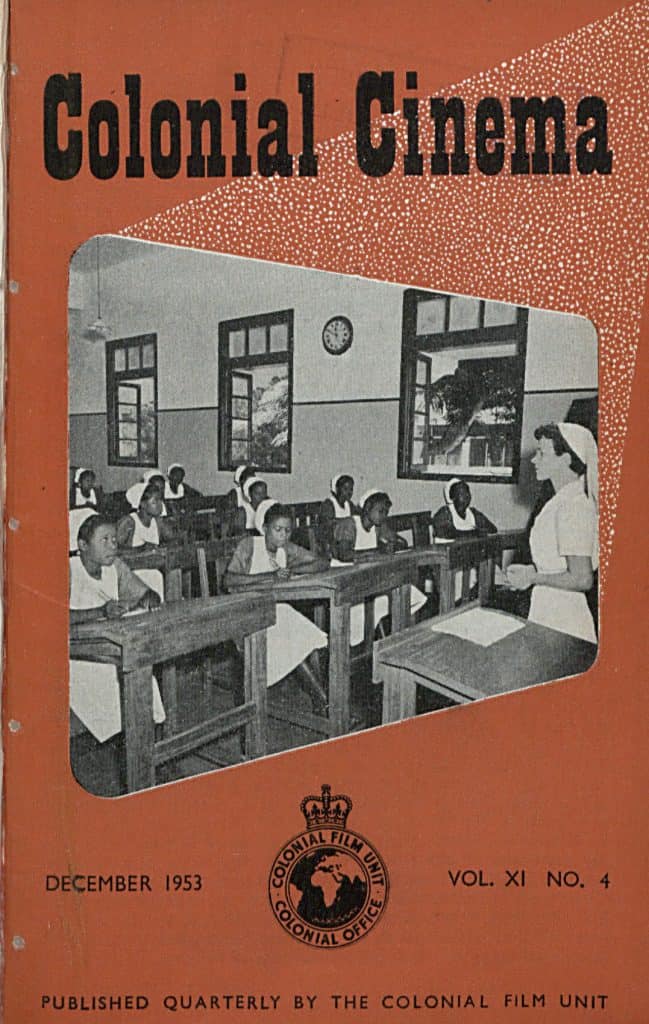

As a study of the British Government’s Colonial Film Unit, which produced, distributed and exhibited films for audiences across the British colonies, the book also moves beyond traditional film histories. While much has been written about John Grierson and the British Documentary movement, this book foregrounds a parallel, critically-neglected history of non-fiction, examining educational and instructional film, playing through mobile cinema vans or in other non-theatrical spaces. The ‘classics’ in this world are films like Mr English at Home or the Gold Coast Film Unit’s Progress in Kojokrom (my favourite tax collection comedy), while the key figures are often civil servants, health officials and educationalists, using film in the colonies as part of the British government’s management of a rapidly crumbling empire.

These histories, materials and personnel, have so often been exorcised or overlooked in film and colonial history. Across the globe I found films (or their traces) that had been willfully ignored, locked away or cut up and repurposed to represent (uncritically) particular historical moments or events. Yet Britain’s failure to confront its colonial past—and to examine critically the media used to promote and preserve the Empire—continues to shape popular attitudes towards race, immigration and indeed Britain’s own position in the world, most evident in the all-pervading discussions on Brexit.

This desire to bring these materials to light prompted me to produce a website to accompany the book, intended for researchers, teachers and students. Working on the assumption that not everyone has seen Journey by a London Bus (1950), I have made available, or organised, primary documents which relate directly to chapters within the book. This includes films—and I link to many on the colonial film website—but also now key writings, unit catalogues, audience reports and pages from Colonial Cinema magazine (1942-1954), the CFU’s in house journal, which I worked with the BFI to digitise. As the book examines the emergence of cinema cultures across the globe, whether looking at the work of a health propaganda unit in Nigeria in the 1930s or training schemes for a first generation of filmmakers in post-war West Indies, it is essential to make these materials freely available beyond Britain. What’s more, bringing these films, materials, and histories out of the archive can allow us to better reflect on the colonial past and to understand its influence in shaping our modern world.