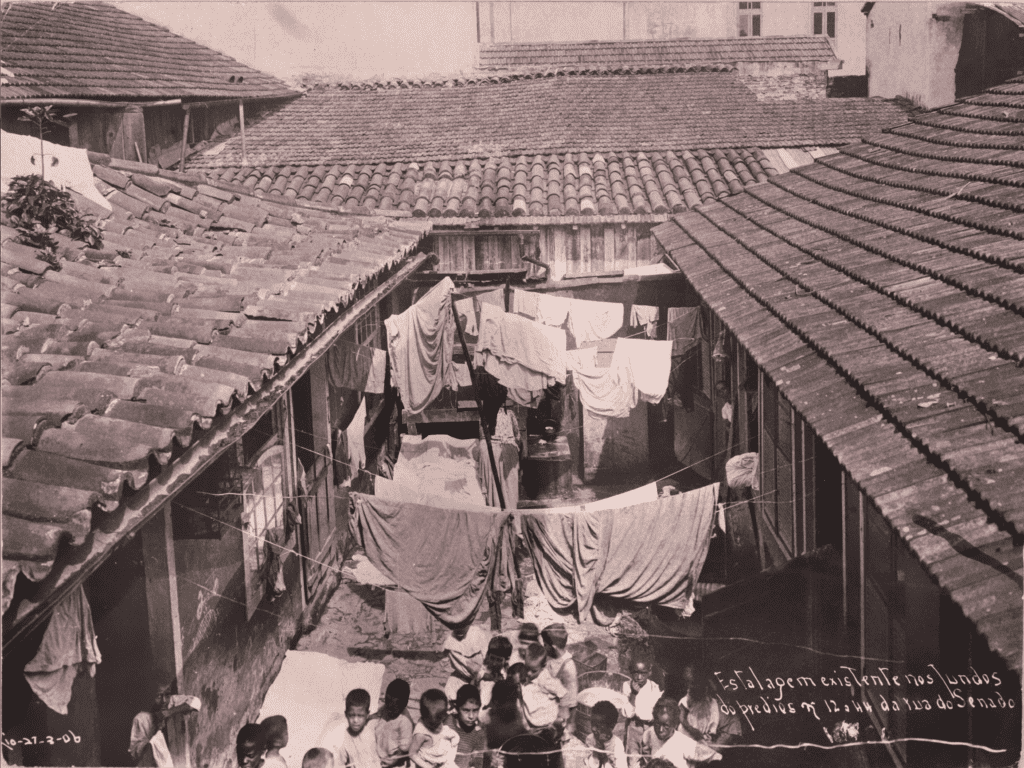

During the early twentieth century, Brazilian photographer Augusto Malta produced a vast archive of photographs of Rio de Janeiro. Through this archive Malta explored two sides of the city: on one hand, the old, epidemic-filled, and diseased Rio and, on the other, the new, modern Brazilian capital of the Belle Époque. My article for issue 2.2 of Latin American and Latinx Visual Culture analyzes the role of affectivity—and Malta’s images—within wider rhetorics of contagion and wonderment that served to justify the expulsion of “undesirable bodies” from select spaces of the city. In turn I argue that affectivity played a central role in enacting a biopolitical agenda and extensively changing Rio’s urban fabric during the early twentieth century.

This topic is timely as we face the current global pandemic and images frantically flood our media-inflated lives. In Malta’s visual discourse, disease—the cause of the recurring epidemics of yellow fever and smallpox—was located in the bodies of Rio’s lower-class and racialized population. His images contributed to an affective economy trafficking in fear of contagion and the desire of an ideal modern city. In contrast, the Covid-19 pandemic has produced an affective rhetoric focused on futurity where images of mass graves and social isolation are juxtaposed with large sets of data. The abstracting power of this statistical language, which is made visual by graphs, charts, and maps works to corral the massive amounts of visual information that expose the biopolitics and necropolitics enacted by governments world-wide against their most vulnerable population.

The discrepancy between the complexes of visuality in Malta’s era and ours are intimately connected to the desires shaping them. In early twentieth-century Rio de Janeiro, justifying mass vaccination and drastic changes to Rio’s image focused on raising foreign investment and enacting social control over the city’s increasing population, a result of the not-so-distant abolition of slavery. Alternatively, in our contemporary moment—with a vaccine a long way from materializing—advocates of a return to normalcy have defended the desperate need for reigniting production, mass consumption, the service industry, and capital speculation. Thus, rather than locating the disease in the body of the Other and generating fear, disgust and anger as in Malta’s rhetoric of contagion, the visual complex of the current pandemic has made the coronavirus increasingly diffuse and its location slippery. On one hand, images such as Pope Francis’ blessing of Urbi et Orbi (the city and the world) in an empty St. Peter’s Square, health workers’ angst stares, and bodies left in the streets of Ecuador have circulated extensively, but they have come embedded with feelings of impotency, helplessness, and melancholy rather than anger and revolt against the governments that put profit ahead of the lives of their citizens. On another hand, statistical data recited ad infinitum by media outlets world-wide has proudly worn its illusory “ontology of calculability” and reduced life to a single number: the mortality rate of the virus, that is, 3.5 % of confirmed cases as of March 3 according to the World Health Organization. As the pandemic exposes the violence of social inequality and the invisibility of countries in the African continent and Latin America in the pandemic’s visualscape, our global system’s power imbalances are muffled by a overdetermined discourse of economic collapse, firmly grounded in statistical predictions.

The most important facet of the affective rhetoric of our current pandemic is its claim to futurity. Determined to continue with postures of absolute denial, protectors of capital such as Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro have defended the need for an immediate return to normalcy and continuously shown disdain for the “weak” seen as heavy burdens on “productive” economies. Others, such as Ecuador’s Lenín Moreno, have pushed austerity measures despite their country’s critical sanitary conditions. For their part, state governors and local leaders in the US—even from the most heavily hit states of the northeast—have spearheaded efforts to lift restrictions. Despite these countries’ acknowledgement of the working class with stimulus packages and programs to incentive job security, their wider rhetoric has been in defense of productivity. This “optimism,” always accompanied by robust statistical data—which has proven easily manipulated—has a clear goal: get the working class back in the streets and reigniting the global economy. Even as the crisis has far outreached initial predictions and countries such as the US, Mexico, Peru, Ecuador, and Brazil experience devastating consequences, a rhetoric of normalcy, with focus on planning for our near future—with the reopening of all sectors of the economy and lifted restrictions—echoes across the American continent. It is an affective rhetoric which traffics on our helplessness, our wish for normalcy, and our fear of the invisible and diffuse threat of an enemy that has not been given a body. At least, not yet.

In a time of flat earth and anti-vax campaigns, of the empowerment of the internet and its networks for disseminating fake news, many have looked to empirical data, statistics, and scientific knowledge as beacons of certainty amidst the chaos. Nevertheless, we cannot forget that these are discursive formations with material implications, they are tools that can be given visual shape and instrumentalized in various rhetorics directed at maintaining structures of power and reinforcing biopolitical control. One thing the COVID-19 pandemic has undeniably exposed is that rather than a carefully crafted rhetoric of contagion to justify the violence and expulsion of “undesirable bodies” from the cityscape, as in Malta’s time, we are now faced with the instrumentalization of our fears and desires, of our society’s most sadistic self-defense impulses, and of large amounts of empirical data to sustain an affective rhetoric of normalcy aimed at making the future present and justifying bare life as the sacrifice demanded by capital in our state of exception.