By Nadya Bair, author of The Decisive Network: Magnum Photos and the Postwar Image Market

A decade ago, August 19 became World Photo Day — a day for photography lovers to celebrate the medium by sharing their best photos with the #worldphotoday tag on social media.

Professional photographers and museums are now taking part as well, but the spirit of world photo day has always focused on a popular enthusiasm for photography. The day commemorates when the ability to fix a photograph became public knowledge. An eyewitness to François Arago’s announcement at the Institut de France noted that the place “was stormed by a swarm of the curious at the memorable sitting on August 19, 1839, where the process was at long last divulged…A few days later, opticians’ shops were crowded with amateurs panting for daguerreotype apparatus…everyone wanted to record the view from his window…”[1] And everyone soon did, not only in France but around the world. Photography quickly became an international past-time and a lucrative profession, especially for entrepreneurial and often itinerant amateurs who could learn to make great pictures faster than they could learn a new language.

Many of the professional photographers who created the influential photo agency Magnum started out as displaced amateurs. As I recount in my new book, The Decisive Network: Magnum Photos and the Postwar Image Market, the legendary war photographer Robert Capa was a Hungarian-Jewish refugee in interwar Paris when he had his initial successes in photojournalism. So was Dawid Szymin, the Polish-Jewish photographer now known as David “Chim” Seymour. In Paris, Capa and Chim met the French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson. All three went on to document the Spanish Civil War from the Republican side, their pictures appearing in the leading illustrated magazines in France, England, and the United States while they became celebrities.

After World War II, these friends came back to an idea they had discussed in the birthplace of photography: to go into business for themselves.

In May of 1947, Magnum was established. This group of photographers, along with the British photographer George Rodger and the American photographer Bill Vandivert, started the international photo agency with an office in New York and in Paris. No less important to early Magnum were two women: Rita Vandivert, who initially sold their pictures from the New York office, and Maria Eisner, the former owner of the French photo agency Alliance and who dealt with European publications from Magnum Paris.

Magnum began by supplying weekly and monthly magazines with in-depth photo essays about global events. Not all of their coverage was exceptional or memorable, but some photos became icons of the postwar world when they appeared in photo books and touring exhibitions. In those contexts, curators, publishers, and photographers themselves codified certain myths about Magnum: its photographers were concerned witnesses to history in the spirit of Robert Capa, or, artists on the hunt for the “decisive moment” like Cartier-Bresson.

Yet my goal in The Decisive Network was to look beyond these narratives and understand how the photojournalism industry actually functioned day-to-day.

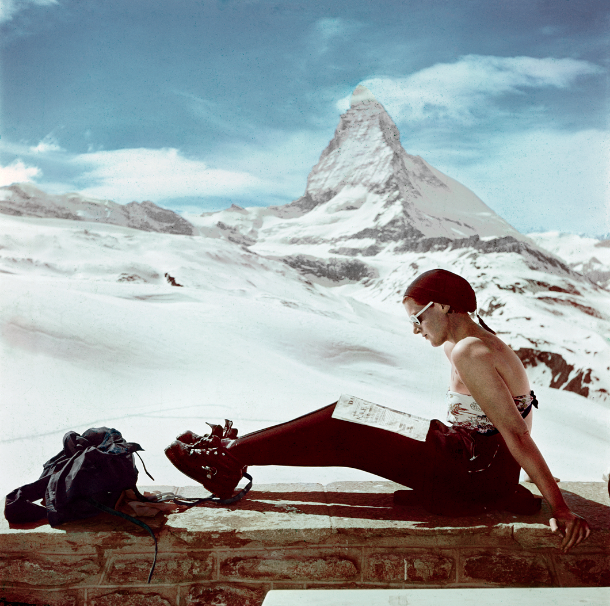

In the course of my research, I was struck by how frequently these now-famous figures appeared in lesser-known publications such as the glamorous magazine Holiday, doing things like skiing in the Swiss Alps while chatting about how to shoot color photos in the snow. Even in the heyday of photojournalism and illustrated magazines, the line between the amateur and professional photo world was blurry, quite purposefully so.

Launched in 1946 as one of the first lifestyle magazines, Holiday aimed to reach a new class and demographic of social moderns. Its editors understood that readers would soon travel the world and photograph it. In the 1940s and 1950s, Magnum photographers shot dozens of stories for Holiday on five continents. In these features, Holiday promoted Magnum photographers as “model travelers” for readers. Stories emphasized the photographers’ picture-taking strategies and philosophies, and offered practical advice on how to get the most out of their travel experiences.

In “The Winter Alps,” published in January 1951, Robert Capa deftly captured blue skies and glistening, snow-peaked mountains, as well as skiers in bright (preferably red) outfits who stood out against the Alpine background. The task of taking great photographs was a recurring trope in the story. Capa revealed that he promised to give skiing lessons to a good-looking American woman if she posed for pictures, and that he later found her a pair of multi-colored ski pants in a French ski shop that were “just right for color photography.” Capa’s advice to readers — which also appeared in the magazine’s short-lived “Holiday Camera” column — ran the gambit of how to become better travelers and truly experience a place instead of simply collecting good snapshots.

Holiday features by Henri Cartier-Bresson, by contrast, turned the photographer’s theory of the “decisive moment” — canonized in his 1952 classic photo book of the same name — into a travel philosophy. For the April 1954 special issue on Western Europe, shot entirely by Cartier-Bresson, Holiday editors used language and layout strategies that were remarkably similar to those in The Decisive Moment. They printed his pictures in large scale on a white background with minimal text. And they composed captions that turned his photo philosophy into guiding principles for the picture-snapping tourist. One of my favorites describes a photo from Venice: “The bow of your gondola knifes into a quiet canal in the little Venetian island of Torcello. And then, just before you shoot under the ancient bridge, a young girl runs over it and is silhouetted for an instant beside the bare trees and against the bright sky…it is only an instant of time, but an instant to remember…” These are directions on how to capture the world like Cartier-Bresson while on your honeymoon or family vacation. If that was not already clear, a Holiday editor added: “The real traveler, like the great artist, learns how to make his instants count, to see with a trained eye the flick of life, the exact moment of significance.”

In light of the current global pandemic, many of us have called off our travel plans and turned our cameras to the momentous events unfolding in our neighborhoods and cities. Even the organizers of the World Photo Day virtual gallery have had to postpone their exhibition plans for next year. We are not necessarily living through a lull in picture production, but some may be experiencing newfound time on their hands to go through old photos and arrange a photo album, or tackle a folder of unprocessed jpeg’s from a past research trip. This kind of time can be precious.

Well before digital photography, Magnum’s photographers struggled to pause and edit their work. In 1958, the agency’s executive editor John Morris half-jokingly called on all photographers to stop shooting for an entire month. He explained in horror that “a story which has taken days or weeks to shoot is often edited in a few hours.” He begged photographers to take photo editing more seriously. But most photographers agreed with Cartier-Bresson when he said, “what excites me is taking the photographic shot; the rest I couldn’t care less about.”

Luckily, Magnum photographers worked with skilled photo editors and agency staff who edited their film and arranged their pictures into photo essays for public consumption. For the first time, The Decisive Network puts these staff in the spotlight alongside the better-known names in photography. And as Magnum’s Holiday stories show, professionals and amateurs were in conversation about picture-making well before most people could fly and take pictures for themselves.

Magnum’s “decisive network” made news images from faraway places a feature of everyday life, fueled by commercial interests — and a popular enthusiasm for photography that continues to this day.

[1] Beaumont Newhall, The History of Photography from 1839 to the Present (New York: The Museum of Modern Art), 23.

Learn more about Magnum Photos in The Decisive Network: Magnum Photos and the Postwar Image Market