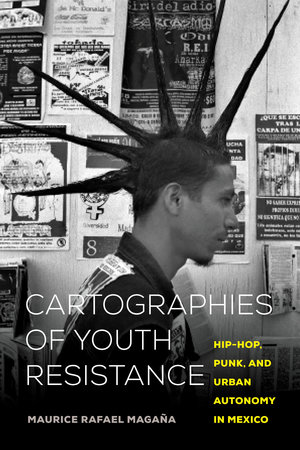

by Maurice Rafael Magaña, author of Cartographies of Youth Resistance: Hip-Hop, Punk, and Urban Autonomy in Mexico

Despite the COVID-19 pandemic and global stay-at-home orders, 2020 has been a year of historic mass mobilizations. The most spectacular constellation of actions has emerged from the Black Lives Matter movement, whose most recent iteration was sparked by the public lynching of George Floyd by Minneapolis Police. The protests quickly spread to hundreds of cities and towns all over the world.

In the United States, protests have been met by nothing short of state and vigilante terror. Federal and local law enforcement, including immigration agents and border patrol, have joined forces to violate the civil and human rights of protestors and bystanders by surveilling, physically assaulting, arresting, and even killing them. Meanwhile these same law enforcement agencies have failed to stop right-wing terror squads from roaming US streets, attempting to intimidate racial justice activists and murdering them in cold blood.

The scale of Black Lives Matter mobilizations has been extraordinary, and has already shifted the political debates around policing and antiblack racism. Eventually, however, mass mobilizations become unsustainable. How can activists continue to push for change?

My book, Cartographies of Youth Resistance: Hip-Hop, Punk, and Urban Autonomy in Mexico, offers an ethnographic account of the life of one movement that was able to remain viable and active long after the original period of mass mobilizations subsided. The movement emerged in the Southern Mexican state of Oaxaca in 2006 after police violently attacked and evicted striking teachers and their families from their union encampment in the capital city’s main plaza. The attack immediately backfired as tens of thousands of Oaxacans rushed to the teachers’ aid, forcing police back to their barracks. Over the next few days and weeks the movement grew to include as many as 1 million people marching through the streets of Oaxaca City demanding the governor’s resignation, a more inclusive state constitution, and an end to the repression of dissent.

Young people played a key role in helping the movement maintain grassroots control of the city for six months through a combination of creative space-making practices, including the use of graffiti and street art to demarcate territory and disseminate news, converting public buildings and spaces into social centers, movement-run radio, and healthcare clinics, as well as erecting a citywide network of self-defense barricades. A sustained campaign of repression from paramilitaries and military-trained federal police left dozens of people dead and the movement eventually lost control of the city. In the months that followed, youth reconvened and began planning the next phase of the movement. They launched a network of political and cultural collectives where they incubated the horizontal political culture that emerged in the more grassroots, yet ephemeral, spaces of the movement in 2006.

The unique politics that youth created and experimented with in these spaces reflected the histories of the activists themselves, many of whom were first or second-generation migrants to the city from Indigenous communities throughout the state. The emergent politics of what I call “the 2006 Generation” combines elements of local Indigenous epistemologies and deep histories of organized resistance, regional social movements, and global youth cultures. One of the noteworthy strands of politics that emerged is what I call “decolonial anarchism,” which draws on urban autonomy, struggles for Indigenous autonomy, magonismo, and liberationist punk-inspired anarchism (anarcho-punk).1

“One of the noteworthy strands of politics that emerged is what I call “decolonial anarchism,” which draws on urban autonomy, struggles for Indigenous autonomy, magonismo, and liberationist punk-inspired anarchism (anarcho-punk).1“

Maurice Rafael Magaña

My book examines how activists used these more quotidian spaces of organizing to expand movement networks, build political power and knowledge, and launch direct actions despite heavy militarization and repression of dissent in Mexico under the guise of the “Drug War.” Importantly, though the spaces I focus on were youth-run, they were intentionally intergenerational and bridged many scales of difference, including ethnic, class, geographic, and political. 2006 Generation collectives and spaces have transformed over the years, with some ceasing to exist and others shifting the political and social focus of their work to focus more on issues affecting their communities of origin like land dispossession and extractivist exploitation, as well as the emergence of “communal feminism” as a powerful organizing force.2

The energy that fueled the massive mobilizations of 2006 in Oaxaca continues to animate the political initiative and imaginations of the young people who came of age during those six months of extraordinary grassroots power. This speaks to one of the main arguments of Cartographies of Resistance—the energy that fuels social movements does not appear out of thin air, nor does is disappear after the moments of spectacular actions ebbs. Instead, that energy transforms into new forms of organizing and sparks new political imaginations and cultures.

“…the energy that fuels social movements does not appear out of thin air, nor does is disappear after the moments of spectacular actions ebb. Instead, that energy transforms into new forms of organizing and sparks new political imaginations and cultures.”

Maurice Rafael Magaña

The mass mobilizations that followed the murder George Floyd seemed to have peaked over the summer, but have not stopped. As long as the police continue to murder Black people, like Breonna Taylor, with impunity, “unrest” will continue. The collective will to imagine a world where Black people can live free of state terror will continue to fuel mobilizations and the everyday organizing needed to sustain them. I hope that the lessons contained in Cartographies of Youth Resistance might help inform how we understand the bravery of those in the streets fighting to ensure that the memories of those killed by police are not forgotten and that the space in our collective soul does not become more crowded with the names of more unwilling martyrs of white supremacy and state violence.

1. Magonismo refers to the anarchist politics of the Partido Liberal Mexicano. Liberationist reflects my rejection of the common translation of libertario as libertarian given the lack of resonance with US Libertarianism.

2. This current of feminist politics is influenced by Aymara activist and artist Julieta Paredes theorizing of “feminism comunitario.”