This post is part of our #MESA2020 blog series. Learn more at our MESA virtual exhibit.

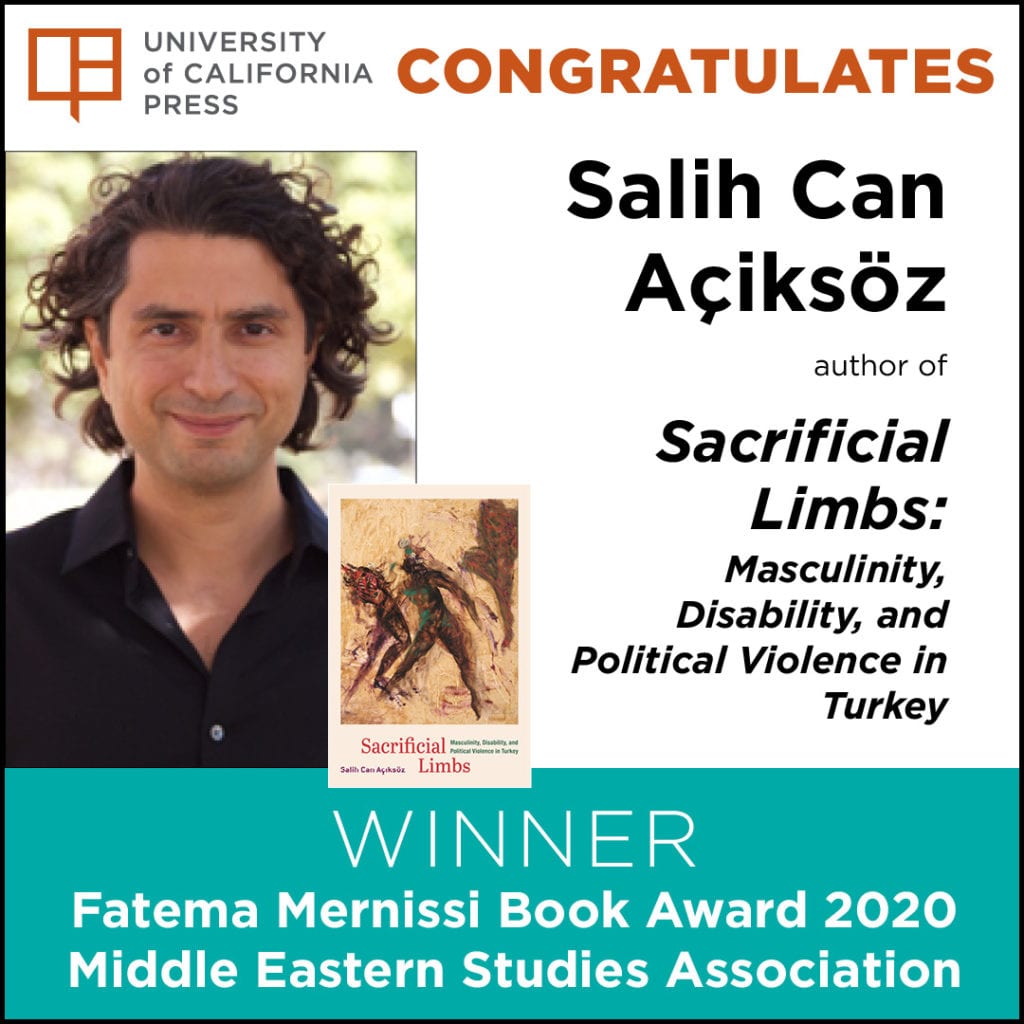

We’re thrilled to announce Salih Can Açiksöz has won MESA’s 2020 Fatima Mernissi Book Award for Sacrificial Limbs: Masculinity, Disability, and Political Violence in Turkey! This award is given to the best work in studies of gender, sexuality, and women’s lived experience.

As part of our virtual MESA 2020 conference series, we reached out to Açiksöz to ask about what motivated him to write Sacrificial Limbs and what he hopes scholars will take away from his award-winning book.

Can you tell us more about your research background and areas of expertise?

I am an anthropologist whose research focuses on the intersections of gender, health, and political violence in Turkey and the larger Middle East. My research bridges the fields of medical and political anthropology, disability studies, and feminist and affect theories. My first book, Sacrificial Limbs, examines the postwar lives and political activism of the disabled veterans of Turkey’s Kurdish conflict. My new book project, tentatively entitled Humanitarian Borderlands, focuses on the political contestations over providing healthcare to combatants along and across the Turkish-Kurdish-Syrian border. I am also interested in the gender and sexual politics of authoritarianism and the ways in which feminist and queer politics can and do inform progressive politics in the Middle East and the US. Finally, I have a perennial interest in reproductive politics. In an earlier project, I worked on new reproductive and medical genetic technologies to examine the polyphonic uses of the notion of risk in relation to gender, biological citizenship, and nationalism. For me, the body is the common thread that ties together these different research projects. I am committed to an anthropological analysis that attends to the body and embodiment as part of its attempt to understand social and political processes.

Sacrificial Limbs is an ethnography of the everyday lives and political activism of disabled veterans of Turkey’s Kurdish war. How did you first become interested in this topic and what motivated you to write the book?

I grew up in Turkey in the 1980s and ‘90s, during the heyday of the Kurdish conflict. I witnessed firsthand the maddening violence that engulfed the country as the state deployed millions and millions of soldiers and paramilitaries in the counterinsurgency against the guerillas of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). In retrospect, I see that the seeds of this project were sown in 1989, when I saw Oliver Stone’s Born on the Fourth of July in a movie theater in Istanbul. Dramatizing the biography of the paralyzed Vietnam veteran and antiwar hero Ron Kovic, the film deeply impacted me as I was discovering the undeclared civil war in my own country. This conflict continues to dictate the parameters of Turkey’s political life, but hitherto no work had been done on the actual subjects—that is, the conscripted soldiers—who have been tasked with fighting this war. I wanted to write a book that would foreground the experiences of former conscripts, who literally embody the costs of the chauvinistic militarism deeply ingrained in the country’s political culture.

Your book examines how Turkish veterans’ experiences of war and disability are often closely linked to gender, class, and political orientation. How does it help us better understand the experience of disabled veterans in other spaces?

The war-damaged bodies of disabled veterans are a ubiquitous but ambivalent presence in modern warring states. Ambivalent because the disabled veteran body embodies the horrors of war yet is often mobilized militaristically as an icon of sacrifice, thereby serving as an affective and ideological impetus for further bloodshed. Ambivalent also because it occupies both the center and the margins of normative masculinity, lionized through the masculine ethos of nationalism, while also being violently expelled from ableist forms of masculine privilege and public citizenship. Ambivalent, finally, because it inhabits an indeterminate space, a sort of “gray zone,” where the distinctions and boundaries between perpetrator and victim, sacred and profane, hero and abject get puzzlingly blurred.

It is often historians, especially those investigating post-world war contexts, who engage with such ambivalences and demonstrate how disabled veterans oscillate between being portrayed as heroes and pauper figures in different societies. The novelty of Sacrificial Limbs is that it ethnographically traces the ways in which these ambivalences are channeled into national politics and then hardened into collective action. Under what historical circumstances do veterans become bearers of ultranationalist militarist ideologies, and what role do their gendered experiences of disability play in their politicization process? These questions are crucial for understanding, for example, a context like interwar Germany, where disabled veterans’ welfare demands and resistance to cultural stereotypes about disability intertwined with political calls for an iron-fisted state and played a key role in the demise of the Weimar Republic and the rise of Nazism. Similarly, these questions push us to think carefully about how disability images and experiences have historically played a role in American veterans’ involvement in white power and militia movements. Further, they can shed light on disabled veterans’ contrasting roles in the making of post-civil war societies across the globe.

MESA’s Fatima Mernissi Book Award is given to the best work in studies of gender, sexuality, and women’s lived experience. What role does masculinity play in your book?

Sacrificial Limbs follows a central tenet of feminist theory—that gender is a constitutive element of social relations and power structures. I use gender as an analytical lens to examine the ways in which the production of gendered and militarized bodies is knotted together with citizenship, sovereignty, and the making of the state. In Turkey, military service is mandatory for (temporarily) able-bodied men, with the exception of openly gay and transgender persons, and is commonly seen as a prerequisite for young men’s employment and marriage. Thus, this male citizenship practice has historically operated as a key rite of passage into heteronormative adult masculinity. For disabled veterans, however, conscription has failed to deliver on its promise of full male citizenship, instead bringing socioeconomic marginalization and exclusion from the marriage market and various forms of domestic and public citizenship. In the book, I describe in detail how disabled veterans’ predicaments are subjectively felt and socioculturally constructed as a masculinity crisis for which the state is accountable. A wide variety of state and non-state actors have responded to this politically charged crisis through medical, religious, and welfare discourses and practices that have aimed to remasculinize veterans and refashion them into productive and reproductive bodies. Yet these remasculinization efforts are by no means straightforward or unproblematic. I trace the quandaries entailed in this process across a variety of fields, ranging from nationalist and media representations to veterans’ care and intimacy practices to veterans’ welfare and political activism. Veterans’ activism is particularly important for the book’s narrative because it is where veterans’ gendered troubles get tangled up with macro political issues. By hitching disabled veterans’ arduous quest to recover their masculinities to ultranationalist agendas, political activism opens up a space in which disabled veterans can once again become masculinized subjects of political violence.

What do you hope students and scholars of anthropology, masculinity, and disability will take away from your book?

Sacrificial Limbs sheds ethnographic light on three broad anthropological questions: First, how can we think about violence as not only a destructive force, but also as a generative force that gives way to new forms of subjectivity and political agency through its embodied effects? Second, what is the role of embodied experience in the constitution of political subjects? And third and finally, how does sacrifice play into modern regimes of sovereignty and state power? In addressing this set of questions, the book joins in the productive dialogue among disability, feminist, and queer studies by highlighting how disability and masculinity get co-constituted at the nexus of militarism, ableism, nationalism, and neoliberalism. Though it builds on the foundational premises of disability studies, the book also challenges Euro-America-centered disability studies to tackle the centrality of war and political violence as global causes of impairment and disability.

Amidst the global trend of right-wing political victories, one of the animating concerns of Sacrificial Limbs has recently become central within the discipline of anthropology: How do right-wing nationalist movements manage to affectively mobilize whole groups of people, especially those who are most harmed by their policies? In attempting to answer this question by placing violently disabled bodies at its center, Sacrificial Limbs provides an account of how a politically engaged anthropology could help us come to grips—morally, intellectually, affectively, and politically—with the suffering of those whose politics we find reprehensible, even inimical, to our lifeworlds, political ideals, and understandings of truth and justice.