By Haidee Wasson, author of Everyday Movies: Portable Film Projectors and the Transformation of American Culture

This guest post is part of our #SCMS2021 conference series. Visit our virtual exhibit to learn more.

Have you ever panicked because you forgot your cell phone at home? As familiar as this feeling is today, we didn’t always feel like this when our gadgets got left behind. There was a time when most people thought carrying media devices around with them was just plain weird.

Consider this. In the 1940s, Radio Corporation of America (RCA) commissioned a study to explore an utterly bizarre proposition. Most radios at this time were basically furniture or, at best, tabletop units for living rooms or kitchens. Yet, RCA wanted to know: If people could carry a radio around, precisely how might it be carried? Over the shoulder? In a suit pocket? On the wrist? One part of the problem they faced was practical: how to persuade humans to carry yet one more thing with them when they moved about. Another part of the problem was more complex: Why? Why should or would people carry a radio with them? At the time, no one quite had a ready or easy answer to this question.

A similar story was also unfolding in the photography industry. Decades earlier, Kodak had launched a national advertising campaign to persuade people that carrying cameras was a new modern way to move about. They surmised that talking about everyday life as essentially photographable would help to increase camera and film sales. But first Kodak had to convince people that cameras were not just for special events, but also essential, everyday things to be worn or carried, like wrist watches or umbrellas. “Take it with you,” Kodak declared. The small Kodak Brownie, and its marketing campaigns, helped to usher in these new ways of thinking about photography as a common, everyday thing and activity.

Many media gadgets have interesting histories that raise questions about size, scale, accessibility and movement, with ideas about what was normal shifting and changing over time. But how do these examples relate to cinema? Few of us would think of cinema as a portable phenomenon. Big movie theaters and huge screens loom large in our cultural imagination. Yet portability does in fact have something to tell us about the long history of movies. We’ve just been looking in all the wrong places.

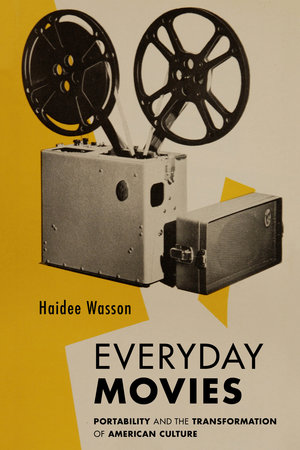

My new book, Everyday Movies: Portable Film Projectors and the Transformation of American Culture, begins with the basic assertion that portable projectors constituted a global, adaptable, moveable, programmable, media platform for more than half a century. Within a few years of prototyping in the 1920s, these little movie machines became crucial instruments of military activity, serving as tools of surveillance, data display, processing and storage, sensory and skill-training, as well as munitions testing. At the same time, small projectors became standard equipment in business and industry. From desktop machines to large, multi-screen, immersive installations at fairs and exhibits, they reshaped internal operations as well as big, outward facing demonstrations of the corporate imagination.

Millions of portable projectors grew into an infrastructure that catalyzed the making of new kinds of films precisely because new audiences to see them became possible.

Haidee Wasson

After World War II, these diminutive cinema machines spread widely, enabling new ways to show movies beyond theaters. Millions of portable projectors grew into an infrastructure that catalyzed the making of new kinds of films precisely because new audiences to see them became possible. Artists, activists, educators, and community organizers rose up, forging films and viewing networks that expanded what, when, why, and how people watched. With these little machines, audiences devoted to topics, styles, and genres of film deemed unsuitable to commercial cinemas found a vibrant life: documentary, religious, educational, international, experimental, underground, political, and explicitly sexual material thrived.

Like other noteworthy technological platforms (Netflix, Youtube), portable projectors constituted a rather surprising, worldwide network that spurred new media uses, new film types, new institutional formations, and an enduring common sense about the place of moving images and sounds in our everyday lives. There were many kinds of projectors: common, specialized, and outright bizarre. Everyday Movies sketches all of this, shedding light on what these projectors tell us about our long, shifting, complex relationship to looking and hearing with small, portable media.